Infamy in Manila

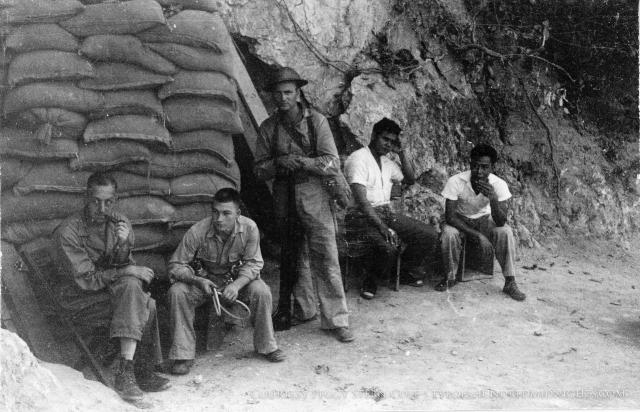

Today is the anniversary of the attacks on Pearl Harbor and the Philippines that brought the United States into World War II as a combatant. In Manila, reporters Melville Jacoby, Annalee Whitmore Jacoby, and Carl Mydans sprung into action to cover the conflict. Here's an excerpt from the book Eve of a Hundred Midnights, by Bill Lascher and published by William Morrow, describing their experience of that harrowing first day.

Newlywed reporters Melville and Annalee Jacoby at work together during the outset of World War II. Photo Courtesy Peggy S. Cole.

Communication lines with Hong Kong were silent.

Radios tuned to Bangkok broadcasts received dead air.

Wireless communications with the United States carried only static.

The streets outside the Bay View were empty.

The morning of December 8, 1941, was deceptively quiet. Then the phone rang.

It was Carl Mydans. Pearl Harbor had been bombed. A newspaper slipped under Carl’s door declared the news in bold headlines. Melville Jacoby didn’t believe his colleague, so he looked at his own paper and “saw some screwy headline that had nothing to do with Honolulu.”

Still doubtful about what Carl had told him, Mel went back to bed, but he couldn’t fall back asleep.

He called Clark Lee, who confirmed the news.

There had been ever-more-frequent Japanese flybys of the Philippines in the preceding days, but still, the news was a shock. “We’d known about the Japanese flights, all the other signs, but we didn’t quite believe it even out there,” Mel wrote.

While Mel was on the phone with Clark there was a knock at his door. He hung up and heard another knock, heavy and insistent. Mel found Carl standing outside the hotel room door, already dressed and ready to head into the city.

That World War II would be fought, and won, in the skies was clear early in the conflict. Though Japan delivered its first blows at Pearl Harbor, more than 6,000 miles across the Pacific from the Philippines, it followed its opening act with devastating raids on two airfields—Clark and Nichols Fields—in the Philippines. Two squadrons of B-17 bombers, dozens of P-40 fighters, and other planes were destroyed, eliminating much of the matériel that had been sent at General Douglas MacArthur’s request.

Despite the news of the attacks in Hawaii nine hours earlier, the planes had been left in the open while their pilots ate lunch nearby. Flyers didn’t receive warnings of the approaching Japanese planes until they were almost overhead.

“By noon the first day, pilots were waiting impatiently on Clark field for take-off orders to bomb Formosa,” Annalee Jacoby wrote, referring to the Japanese-occupied island now known as Taiwan. “Our first offensive action had to wait for word from Washington — definite declaration of war. Engines were warmed up; pilots leaned against the few planes and ate hot dogs.”

Twenty minutes later, without warning, Annalee wrote, fifty- four enemy bombers arrived, delivering a brazen, devastating raid on Clark Field that crippled an already underprepared American garrison.

These raids sparked a decades-long debate about who was responsible for the blunder, but whoever should be blamed, the United States lost fully half of its air capacity in the Philippines in this one devastating first day of the war.

“MacArthur’s men wanted to fight—but most of all they wanted something to fight with,” Mel wrote in a flurry of cables he sent Time following the war’s commencement and the air- fields’ decimation. Unfounded rumors of convoys and flights of P-40s coming to join the fight began almost as soon as the attacks subsided. They would not cease for months.

On that morning, Manila’s Ermita neighborhood was quiet. Mel arranged a car for the Time employees to share. Together they raced up Dewey Boulevard, to Intramuros, the walled old- town district that had been Spain’s stronghold during its 300- year occupation. When they reached the U.S. Army Forces in the Far East (USAFFE) headquarters at 1 Calle Victoria, they found MacArthur’s driver, who had arrived early in the morn- ing, asleep in his car.

“Headquarters was alive and asleep at the same time,” Mel wrote. MacArthur’s staff was weary-eyed but busy as they girded for war. Within hours, helmeted officers carrying gas masks on their hips raced back and forth across the stone- walled headquarters, stopping only briefly to gulp down coffee and sandwiches. The general himself was his usual bounding self, striding through the headquarters as staff and other wit- nesses confirmed reports of attacks throughout the Philippines. Mel and Carl were concerned about their jobs. Would wartime censorship clamp down on their reporting?

“The whole picture seemed about as unreal to USAFFE men as it did to us,” Mel later wrote. “We couldn’t believe it, and MacArthur’s staff had hoped the Japanese would hold off at least another month or so, giving us time to get another convoy or two in with the rest of the stuff on order.”

This hesitation, of course, was partly to blame for the devastation that occurred that day and the unsettled footing with which American forces fought during the brutal months to come.

Meanwhile, deep-seated racial prejudices kept many Americans from believing that Japan was capable of carrying out the attacks.

“Those days were eye-openers to many an American who had read Japanese threats in the newspapers with too many grains of salt tossed in,” Mel wrote. “They still couldn’t believe the yellow man could be that good. It must be Germans; that was all everyone kept saying. We were just beginning to pay for years of unpreparedness. The shout ‘It’s Chinese propaganda’ had suddenly lost all traces of plausibility.”

Regardless of who was to blame, U.S. forces reeled.

Manila was quiet even as chaos engulfed the headquarters, where a scrum of reporters waited for updates. Rumors flew beneath the shady trees of Dewey Boulevard, rippled up the Pasig River, and raced past the storefronts along the Escolta.

“The whole thing has busted here like one bombshell, though, as previous cables showed, the military has been alert over the week,” Mel would soon write.

As the realization of what had begun set in, Manila residents rushed through the city, withdrew cash from banks, stocked up on food, and bought as much fuel as they could before rationing was ordered. Businesses quickly transformed basements into bomb shelters. Sandbags became scarce. As would happen all over the United States, local military rounded up anyone of Japanese descent, whether they were Japanese nationals or not. The Philippines waited for war.

From Eve of a Hundred Midnights, by Bill Lascher and published by William Morrow (2016). For the story of the Jacobys' last-minute escape from the Philippines and to learn about their work as war correspondents in China and the Philippines, find Eve of a Hundred Midnights at your favorite bookseller, or order it from Indiebound, Powell's, Amazon, or Barnes & Noble.

Into the Blackness Beyond

"We are remembering MacArthur’s men, how hard it was to finally leave, how lucky the three of us are."

On February 23, 1942, Seventy-five years ago as I write, Melville and Annalee Jacoby crossed the two-mile-wide channel between the fortress island of Corregidor and the besieged Bataan Peninsula for the last time. There, there would wait until sundown when a small inter-island freighter, the Princesa de Cebu, arrived in the channel, ready to sneak through the Japanese blockade surrounding the Philippines' largest island, Luzon. Their hope: escape to unoccupied portions of the Philippines and then, if they were lucky, find another ship through Japanese waters to allied territory. Here is the story of that night as told in the bestselling book, Eve of a Hundred Midnights:

“We sit by the side of a Bataan roadway waiting,” Mel wrote as he and Annalee absorbed their last moments on the peninsula amid a thick knot of banyan trees near the shore. “Our visions of past months of war are vivid, clouded only momentarily during this waiting by thick sheets of Bataan dust rolling off the road every time a car or truck races by. We wonder for a moment when we will return—and how.”

Finally, escape was in sight. At dusk, a launch would arrive to take the Jacobys to the Princesa de Cebu. That ship, they hoped, would then slip past enemy patrols at the mouth of Manila Bay and carry the reporters through the Philippines—possibly even farther across treacherous, Japanese-controlled sea-lanes and on to refuge in Australia, thousands of miles to the south.

Through a pair of binoculars borrowed from a soldier on the Bataan coast, Mel peered south toward Manila. He thought he could see the rising sun of the Japanese flag fluttering over the Manila Hotel, the same place where he’d had his last Christmas dinner, where Annalee had danced with Russell Brines and Clark Lee had urged Mel to flee the Philippines. He knew that Carl and Shelley were somewhere beneath that fluttering crimson-and-white banner. A reliable confidential source had told Mel that the Mydanses were among the thousands in captivity at Manila’s Santo Tomas University, which the Japanese had turned into an internment camp. However, it had been a month since that report.

That day Mel and Annalee felt as “impregnable as the mountain,” almost invincible “for the first time in this war.” Finally, they were leaving, Mel wrote, recalling people and moments from his six weeks on Corregidor and Bataan. Leaving everything. Leaving General Douglas MacArthur. Leaving the general’s trusted lieutenants, who had become their friends. Leaving the scores of men they’d met at the front whose stories had yet to be told. They were leaving all of them behind, “most of all the scared Pennsylvania soldier who ran the first time he heard [Japanese] fire but who braved machine gun fire the second time to carry his officer off the field.”

As the Jacobys walked along the tree trail, a Jeep carrying two officers skidded into the dirt. The noise and dust shook Annalee and Mel back into the moment. They stood up and greeted the officers. It was the first time Mel really registered the weariness on the faces of those fighting in Bataan. Despite the fatigue in their eyes, neither officer mentioned their exhaustion. Instead, they chatted casually, sharing rumors and battlefield legends until the soldiers finally drove off a few minutes later. Mel and Annalee again turned to thoughts more hopeful than the soldiers’ exhaustion. Like thoughts of ice cream sodas. Could they ever taste as good as they imagined?

Finally, the sun began to set. It was time.

The couple ran back toward the shore along the tree trails. One path led to the last American planes remaining in the Philippines, the rickety trainers, a couple of obsolete fighters, the P-40 so “full of holes.” The planes were hidden next to an airstrip that resembled a hiking trail more than a runway.

Mel and Annalee were barraged by memories at each turn. They passed anti-aircraft batteries, a motor pool, a machine shop, even a bakery (though one that had never had bread to bake) and a makeshift abattoir where first caribou, then mules, then even monkeys were slaughtered for the soldiers’ meals.

Across the narrow channel from Bataan, Clark Lee had finished wrapping up his own affairs on Corregidor, and now he was waiting for the Jacobys at the same dock on the island’s north side where the trio had come ashore on New Year’s Day. He did bring a typewriter, as well as a razor, a toothbrush, and a change of clothes.

The Princesa approached at dusk, slowly steaming westward. They boarded and were greeted by four British and two American civilians who had received field commissions after fleeing from Manila to Bataan. They had boarded the Princesa from a separate launch earlier. Among them was Lew Carson, a Shanghai-based executive for Reliance Motors hired by the army to help manage its motor pool, and Charles Van Landing-ham, a former banker who escaped to Bataan on a tiny sailboat on New Year’s Eve. Also a contributor to the Saturday Evening Post, Van Landingham was struck by how deceptively peaceful the green jungles of Bataan looked as he left.

“It was hard to realize that under that leafy canopy thousands of hollow-eyed, half-sick men stood by their guns, fighting on grimly in the hope that help would come before it was too late,” Van Landingham wrote.

Its lights dark, the Princesa slowly made its way into mine-laden Manila Bay. Huge searchlights on Fortuna Island scanned the sky above the island as its “ack-ack” guns—anti-aircraft artillery—fired at Japanese bombers. The darkness gave way momentarily to the glow of the guns’ tracers, which lit the passengers’ faces. Then night returned across the ship’s deck.

From Corregidor, a searchlight swept the coast in front of the Princesa. A small, fast torpedo boat appeared and led the ship through the mines, barely visible but for the path carved by its wake. The craft was skillfully piloted by Lieutenant John D. Bulkeley, who provided a few minutes of covering fire while guiding the Princesa toward the mouth of Manila Bay. Then, in a final farewell gesture, Bulkeley flashed the torpedo boat’s starboard light and roared back to Bataan, leaving nothing but darkness in his wake.

Night on the Pacific washed across the Princesa. Only the distant flash of Japanese artillery punctuated the dark. The ship’s two masts bobbed beneath what Mel’s eyes found to be a “too bright moon.” This was the same moon the soldiers on Bataan prayed would descend quickly, lest even a quick glint of its light across a shining service rifle’s barrel draw a sniper’s bullet. Now the moon cursed the Princesa. The nearby shore was dark, but everyone aboard the Princesa knew it crawled with enemy forces. They silently watched the passing islands. Each lurch of the ship tied the passengers’ stomachs in a “tight feeling.”

A crew member snapped a chicken’s neck. The reporters jumped at the bird’s sudden, loud squawk.

It was just dinner, but everyone crossed their fingers.

“Sure, we’ll make it,” someone said. “Easy.”

All three reporters rapped their fists on the wooden deck.

Nobody slept. Everyone kept watch, fearful of missing even the briefest moment of movement. Finally out of Manila Harbor, the ship maneuvered toward the southeast and crept through the darkness along Batangas, on the Luzon coast south of Manila.

Thousands of miles, countless inlets and islands, circling recon planes, even submarines and destroyers dispatched by the Philippines’ new conquerors lay between the reporters and safety in Australia. They spoke little. Instead, they reflected privately on the soldiers they had met on Corregidor and Bataan, the onslaught both places had endured, and their own good fortune so far.

“We talk very little sitting on deck now. We are remembering MacArthur’s men, how hard it was to finally leave, how lucky the three of us are. We’d gotten through the [Japanese] before,” Mel wrote. “Everything we’ve known the past two months is swallowed in blackness beyond.”

75 Years Ago, When War Seemed a Million Miles Away

75 years ago, today, Pearl Harbor was on the horizon, but for one couple in Manila, war briefly felt a million miles away.

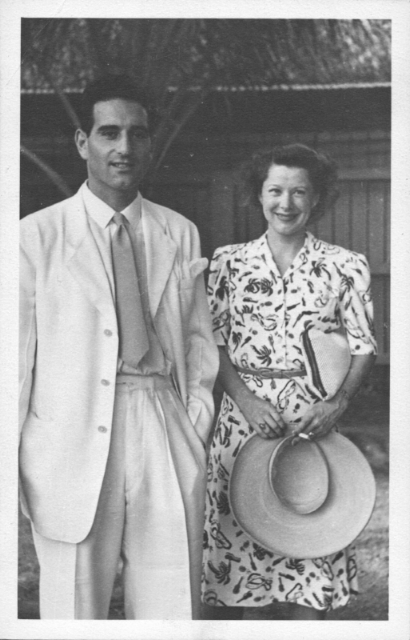

Seventy-five years ago, today, with the United States and Japan on the brink of war, Time Magazine correspondent Melville Jacoby married the former Annalee Whitmore, a former MGM scriptwriter who had been managing publicity for an aid organization known as United China Relief. The following excerpt from Eve of a Hundred Midnights (William Morrow, 2016) describes the moment Annalee arrived in Manila from Chungking, the wartime capital of China, and Mel whisked her off to their wedding. Pick up the book from your favorite retailer to find out how Mel and Annalee's paths crossed, and what happened when war broke out just two weeks after their wedding.

From the edge of Pan-Am’s facilities along the southern arc of Manila Bay near the Cavite shipyard, Mel watched a Boeing 314 cross the sky. It was Monday, November 24, 1941, just three days before Thanksgiving.

Annalee was on the plane. As it landed she spotted Mel at the water’s edge, clad in a gleaming white suit, white shirt, and yellow tie.

“I could see him when the plane landed in the water, and it seemed like hours until they pulled it up onto the beach,” Annalee later wrote to Mel’s parents.

Finally, the Clipper’s pilot cut the aircraft’s engines. The plane coasted the last few feet to the dock, where its passengers disembarked. Annalee barely had time to say anything to her fiancé. After they embraced, Mel ushered her to a waiting car, which drove the ten miles from Cavite to Manila, turned right off Dewey Boulevard onto Padre Faura, then stopped at the Union Church chapel a couple of blocks away. Mel strode confidently up to the church, while Annalee, wearing a white nylon dress printed with palm trees, ukuleles, pineapples, and leis in green, yellow, and red, linked her arm in his, smiling widely, a broad-brimmed yellow hat tucked under her other arm. For a couple who never expected romance, it was as dreamlike as any fairy tale.

“It was just like I’d always hoped it would be,” Annalee wrote.

Carl and Shelley Mydans were there, as well as Allan Michie (a Time reporter about to transfer to England, Michie was also the author of Their Finest Hour) and the Reverend Walter Brooks Foley. As soon as the couple arrived, the small pro- cession gathered in an intimate reception room off the chapel decorated with white flowers and green drapes. Carl served as Mel’s best man; Shelley was Annalee’s matron of honor.

Reverend Foley performed the modest ceremony. Mel had always dreaded large, formal weddings. He had looked for a justice of the peace to officiate, but most of the ones he found spoke little English and held ceremonies in nipa huts—small stilt houses with bamboo walls and thatched roofs made from local leaves.

“The morning I came he found Reverend Foley, who was a short blond near-sighted angel, full of extravagant plans for choir chorales and processionals and borrowed bride giver-awayers,” Annalee wrote.

Annalee may not have wanted a big to-do or an ostentatious ring, but she clearly couldn’t restrain her delight at the occasion itself. Her smile did not subside throughout the ceremony. Her hands gently clasped Mel’s as they exchanged vows, and she looked intently at her husband, her eyes grinning and warm. For his part, Mel couldn’t mask the pride on his face, nor his joy.

Within an hour of Annalee’s landing, she and Mel were married. After their wedding, they wrote letters to their families. In one, Annalee insisted to Mel’s parents that she didn’t go to China to marry Mel, but she “couldn’t think of a better reason” to have gone.

The celebration continued at the Bay View Hotel, just a few blocks away. Gathered in the lobby were many of the couple’s friends who had also transferred to Manila from Chungking, as well as others Mel had met since arriving. Those who couldn’t be there sent their congratulations. Everyone, from Annalee’s colleagues at MGM to Henry and Clare Boothe Luce, to all the Press Hostel residents, to the entire staff of XGOY (which also aired a brief item about the marriage), sent their good wishes.

“General MacArthur about knocked me over the other p.m. congratulating me,” Mel wrote. “Admiral [Thomas] Hart’s staff nearly shook my hand off.”

There was a portable phonograph setting the tune with jazz standards and popular big band recordings. In between songs, the newlyweds ducked into a corner of the lobby where they took turns placing long-distance phone calls to their parents in Los Angeles and Maryland. And then they danced into the night. War was on the horizon and could arrive any day, but that evening it could have been a million miles away.

A Wedding At The Brink of War

For a brief moment after the wedding, the world fell away from Mel and Annalee. That they didn't have the traditional wedding their friends in the Chinese government wanted to throw for them back in Chungking didn't matter. That all their things — including most of Annalee's clothes — were on a ship that would end up diverted from Manila when the war started didn't matter. They were two young reporters in love.

Mel and Annalee walking together through Manila on their wedding day.

Seventy-two years ago today, mere days before Pearl Harbor, two young journalists from California married as war clouds gathered over Manila. Melville and Annalee Jacoby had met at Stanford and reconnected in the Spring of 1942 when Mel briefly went home to the United States. Annalee arrived in Chongqing n September, 1941, and the couple quickly fell in love. Mel proposed as the couple raced through Chongqing's steep streets on rickshaws, their drivers dodging crowds and bomb-blast potholes, but the next day Time asked him to transfer to Manila. Annalee had work to finish and wouldn't join him for two months. They got married the day she arrived in Manila, Nov. 26, 1941. Their romance is one for the ages, and it's the heart of the book I'm working on about Mel. Here's an excerpt from that book about the wedding day that I've adapted a bit for this space). Happy Anniversary!

That day, Mel waited on the shoreline for her plane to land. The approach to the beach seemed to Annalee to take hours. The entire time she eyed Mel by the side of the water in his gleaming white suit, white shirt and yellow tie.

As soon as Annalee stepped off the plane, Mel whisked her off to the Union Church of Manila. Her wedding gown a casual white nylon dress covered in prints of palm trees, ukuleles, pineapples and leis, Annalee strolled along a Manila street with one hand clutching Mel's arm and a yellow, broad-brimmed straw hat tucked under her other arm. She beamed as she looked up at him. He strode confidently, almost smugly.

“It was just like I'd always hoped it would be,” Annalee said.

Mel had wanted a justice of the peace, but the search for one who could speak English had ended up a comedy of errors and cultural clashes, so he chose the Union Church’s Reverend Walter Books Foley. Foley performed the ceremony in a small room off the chapel decorated with white flowers and green drapes. Mel had spent $746 on two rings: a simple platinum band, and another with a square 1 ½ carat diamond head and small diamonds branching off along its platinum mount.

“Looks like half a milk bottle it is so big,” Mel told his parents.

Life photographer Carl Mydans was Mel’s best man. Mydans’s wife, Shelley, a writer for Time and Life and a mutual friend of Mel and Annalee from Stanford, was the matron of honor. The only other guest at the ceremony was Allan Michie, another Time reporter. After the ceremony, other friends of Mel's met the newlyweds at the Bay View Hotel, where they danced around a portable phonograph, called home and celebrated.

For a brief moment after the wedding, the world fell away from Mel and Annalee. That they didn't have the traditional wedding their friends in the Chinese government wanted to throw for them back in Chungking didn't matter. That all their things — including most of Annalee's clothes — were on a ship that would end up diverted from Manila when the war started didn't matter. They were two young reporters in love.

“He types on the desk, and I type on the dressing table, and we both feel awfully sorry for the people next door,” Annalee told Mel’s parents.

Mel and Annalee Jacoby's Wedding at the Union Church of Manila.

Mel and Annalee slipped away for a brief honeymoon at a cabin near the Philippine town of Tagaytay, as much a tourist destination then as it is today. Their cabin overlooked the stunning lake Taal and the volcanic island at its center. The shack's electricity didn't stay on through the night and the faucet dripped, but they were happy to be able to escape — if just for a weekend — from a war that was then just days away.

Tied up next to the cabin were two baby giant pandas. Madame Chiang had entrusted Mel and Annalee with the animals’ care — not an easy feat — until they could be loaded onto the Calvin Coolidge, the last passenger ship to leave the Philippines before the war began.

Aside from the Pandas, the couple received a bevy of luxurious and stately gifts from their friends and contacts in China. These included red satin blankets, elaborate vases and piles of greetings from other journalists they knew in Chungking. Hollington Tong — China’s information minister and Mel’s former boss — gave them cash because he couldn't throw a “Red Sedan” wedding for the Jacobys. Such a traditional ceremony would have involved drummers, fine clothing and an elaborate chair. But the conflict made that celebration impossible.

Despite headaches caused by caring for the pandas, the intermittent services at the cabin and a rainstorm, the Jacobys were not dismayed, as Annalee explained in a letter to Mel's parents:

“The running water worked only at intervals, the electricity blinked on and off all one evening, and it poured, but it was still the most wonderful honeymoon anyone ever had.”

Search Posts

Archived Posts

- March 2024 1

- October 2023 1

- October 2022 2

- December 2017 1

- April 2017 1

- February 2017 1

- January 2017 1

- November 2016 2

- August 2016 2

- July 2016 2

- December 2015 1

- November 2015 2

- September 2015 3

- April 2015 1

- March 2015 1

- February 2015 1

- January 2015 4

- August 2014 1

- May 2014 1

- April 2014 4

- March 2014 6

- December 2013 1

- November 2013 1

- August 2013 3

- May 2013 2

- April 2013 1

- December 2012 3

- November 2012 2

- October 2012 2

- September 2012 3

- August 2012 6

- July 2012 4

- June 2012 1

- May 2012 6

- April 2012 2

- March 2012 3

- January 2012 2

- September 2011 2

- August 2011 2

- July 2011 1

- May 2011 9

- April 2011 2

- March 2011 1

- January 2011 2

- November 2010 1

- October 2010 1

- August 2010 3

- July 2010 1

- June 2010 1

- May 2010 12

- April 2010 2

- March 2010 1

- January 2010 1

- December 2009 1

- November 2009 4

- October 2009 2

- September 2009 2

- August 2009 1

- July 2009 1

- June 2009 4

- May 2009 1

- March 2009 5

- February 2009 4