Introducing A Danger Shared

Read an excerpt and view photos from the book A Danger Shared: A Journalist’s Glimpses of a Continent at War (Blacksmith Books, 2024), which features photography by wartime foreign correspondent Melville Jacoby and accompanying text by Bill Lascher.

The following text and images were excerpted from the introductory chapter to the book A Danger Shared: A Journalist’s Glimpses of a Continent at War (Blacksmith Books, 2024), which features photography by wartime foreign correspondent Melville Jacoby and accompanying text by Bill Lascher, who wrote about Jacoby in the critically acclaimed 2016 book Eve of a Hundred Midnights: The Star-Crossed Love Story of Two WWII Correspondents and Their Epic Escape Across the Pacific (William Morrow & Co.).

The 75th anniversary of the end of the Second World War had just passed when I began writing this introduction on September 11, 2020. That date also marked 104 years to the day since the birth of Melville Jacoby, the American foreign correspondent whose images of the war comprise the majority of those included in this book. Mel’s life was short but impactful, capped by a career a close friend called “as brilliant as it was brief.” That brilliance Mel devoted to covering the war and bridging the distance between two physically and culturally distant lands: the United States and Asia.

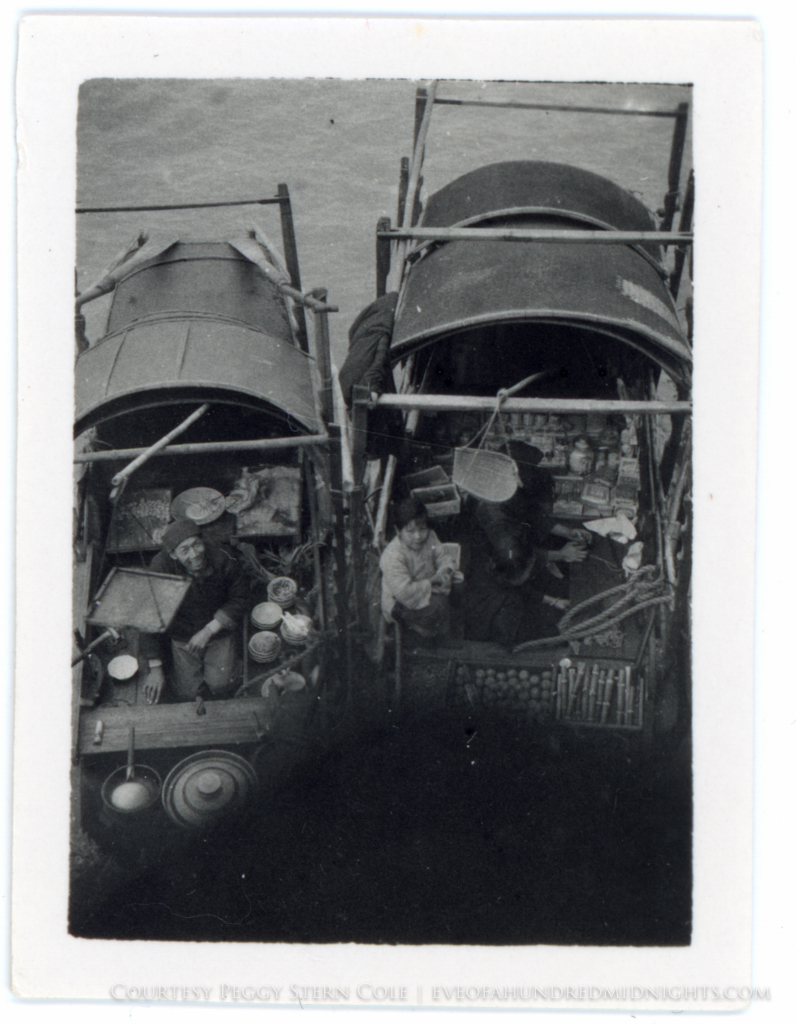

Mel documented the war and its impact as part of a broader mission to help Americans better understand China (and, later, the Philippines and the place then known as French Indochina). Having studied, lived and worked in China, Mel was understandably interested in how coverage of the war might influence Americans’ sympathy, or lack thereof, for his Chinese friends, neighbors, and colleagues. He also foresaw the weighty implications of the conflict for the United States. Interdependencies and connections had been evolving between Pacific-facing nations before the war. Mel understood this impact on the Pacific and how the conflict between the people and societies on one side of it increasingly mattered to those on its opposite shores.

That morning in 2020 I was, of course, writing amid another crisis: the Covid-19 pandemic. The coronavirus outbreak and responses to it were widening pre-existing political, social, and cultural rifts. This reminded me of a similar crisis, the influenza pandemic of 1918-1920, which claimed Mel’s father’s life when Mel was just two years old. I put this collection together because our lives are more connected than we often realize or care to admit. Wherever and whenever we live, we deserve to have our stories remembered. Our memories are intrinsically valuable, but we are also better able to highlight our connections when we take effort to surface and preserve not just our own stories, but those around us.

The anniversary of the Second World War’s end passed quietly. Our year of contagion, political unrest, and climate catastrophe obscured any inspiring observances of the victory over fascism, moving appearances by veterans, or somber reflections upon atrocity and sacrifice that might have been. What could have been a year of remembrance instead was drowned out by the noise of “2020,” a term that became popular shorthand for calamity and left little room for memory.

Tens of millions of people were killed and displaced during the war in Asia, where the conflict’s global consequences still resonate. Still, Asia’s experience of the war remains largely an afterthought in other parts of the world. Even before the pandemic, the war in Asia was not widely remembered elsewhere. For three quarters of a century, countless tomes about World War II have dissected every nuance of the struggle for Europe, and most of those that don’t instead address America’s crusade through the Pacific. In the Americas and Europe at least, comparatively few titles document the conflict’s massive human and economic toll in Asia, where fighting began two years before Germany invaded Poland and four years before that infamous Sunday morning in Pearl Harbor, Hawaii.

Melville Jacoby at the Press Hostel

Melville Jacoby sits in front of the ruins of the Press Hostel in Chungking in the summer of 1941. In the photo, Mel clasps a flashlight, suggesting he’d just returned from one of the city’s dark, dingy air raid shelters or was prepared to enter one at short notice.

Melville J. Jacoby Press Hostel calling card (fron

The Chinese-language side of Jacoby’s card

Press Hostel calling card (reverse)

Melville Jacoby’s calling card while working in Chungking (Chongqing), China, circa 1940-1941

This collection can’t fix that reality, but it may help resurface the story of Asia’s experience of the war while reviving the memory of those who tried to chronicle it. Many of the images you see within this collection have never been published. Curating and interpreting them has expanded my knowledge of World War II, shifted my understanding of war in general, and deepened my appreciation for those who sacrifice their lives to document world-rending moments.

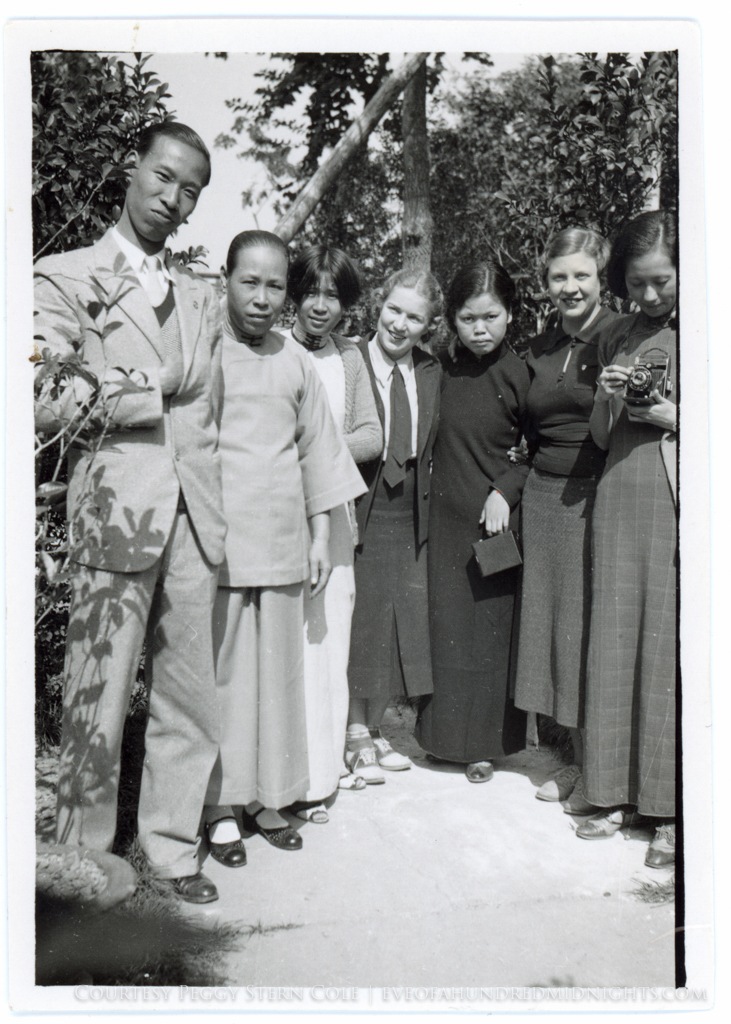

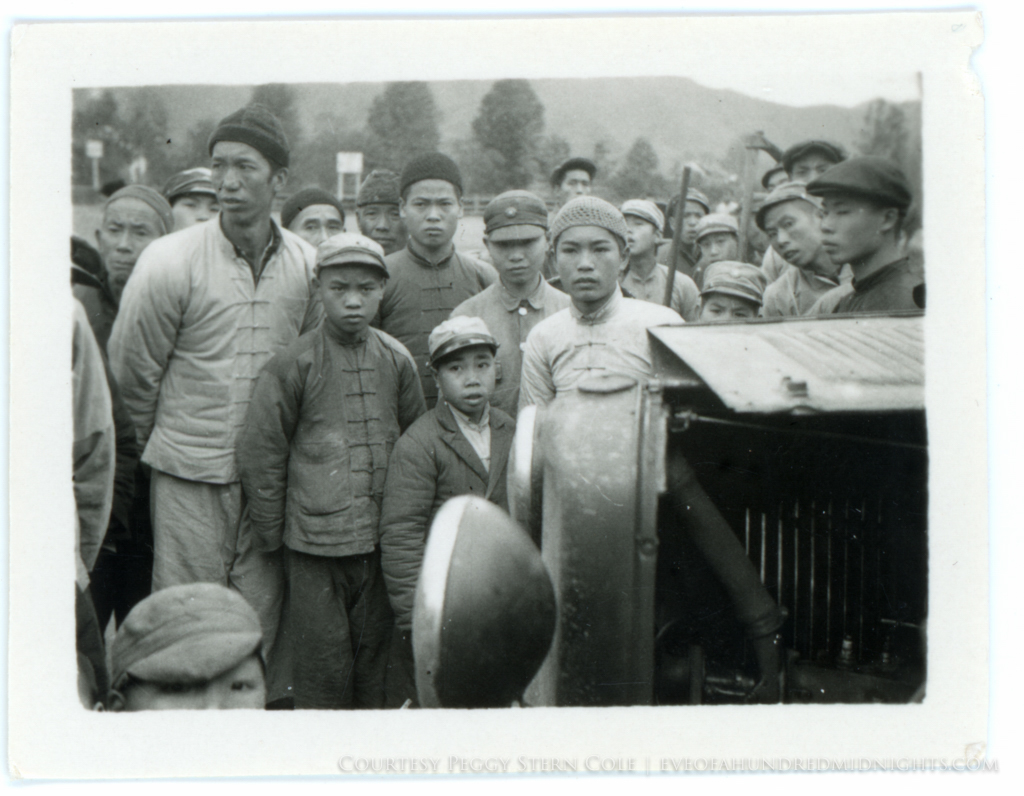

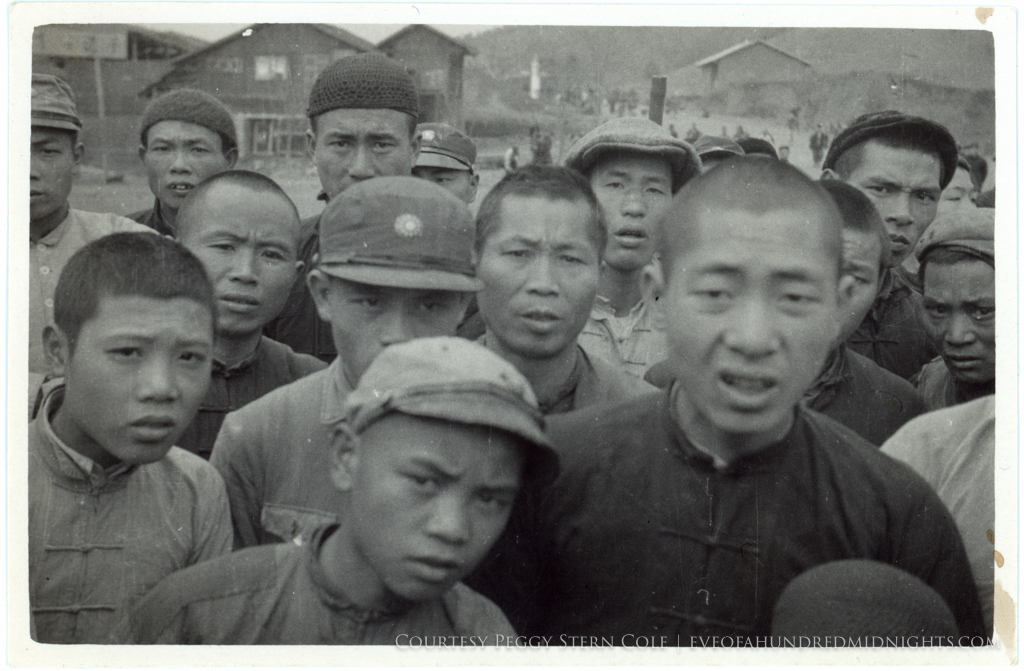

The Faces I see every day

A photograph of mostly Chinese nationals photographed by Melville Jacoby, who wrote “The Faces I See Every Day” on the back of the print. Mel likely made this image while a student at Lingnan University in Canton (Guangzhou), China, in the 1936-1937 school year.

That deepening began twenty years ago, when my grandmother — Mel’s cousin — gave me a typewriter that used to belong to him. I was in my early twenties. As I learned more over the ensuing years, that story has maintained a presence in my mental landscape. Learning about Mel was at first an excuse for me to spend time with my grandmother. She’d ended up with most of his possessions, and each time I visited, I learned a bit more about him. By 2016 I’d gathered enough material to write my first book, Eve of a Hundred Midnights (William Morrow), which describes Mel’s life, his romance with the equally remarkable journalist Annalee Whitmore Jacoby, and their escape together from the doomed Philippines.

As interesting as those two were, there was a bigger story to tell. That book really only touched upon a small segment of what’s contained in the hundreds, maybe thousands of photographs, letters, and notebooks of Mel’s I’d grown to look forward to seeing at my grandmother’s house (let alone elsewhere). Mel and Annalee’s story was worthy of a book, but leaving out all this other material did a disservice to the work they and the people close to them produced. These young, passionate reporters had written exhausting, illuminating accounts of the war — both for private and public audiences. They also captured vivid images of conflict as well as the beguiling way everyday life persists in spite of it. What good were these chronicles they’d devoted their lives to capturing if they remained stuffed in some closet in California for decades?

I regularly reflect on what didn’t make it into my book’s pages. I’ve focused on telling other stories since, but part of me still thinks about the ones Mel told, the ones he didn’t tell, and the ones nobody had a chance to tell. More than any of that, I wonder about what stories I don’t even know about, which stories were left untold and forgotten by the world.

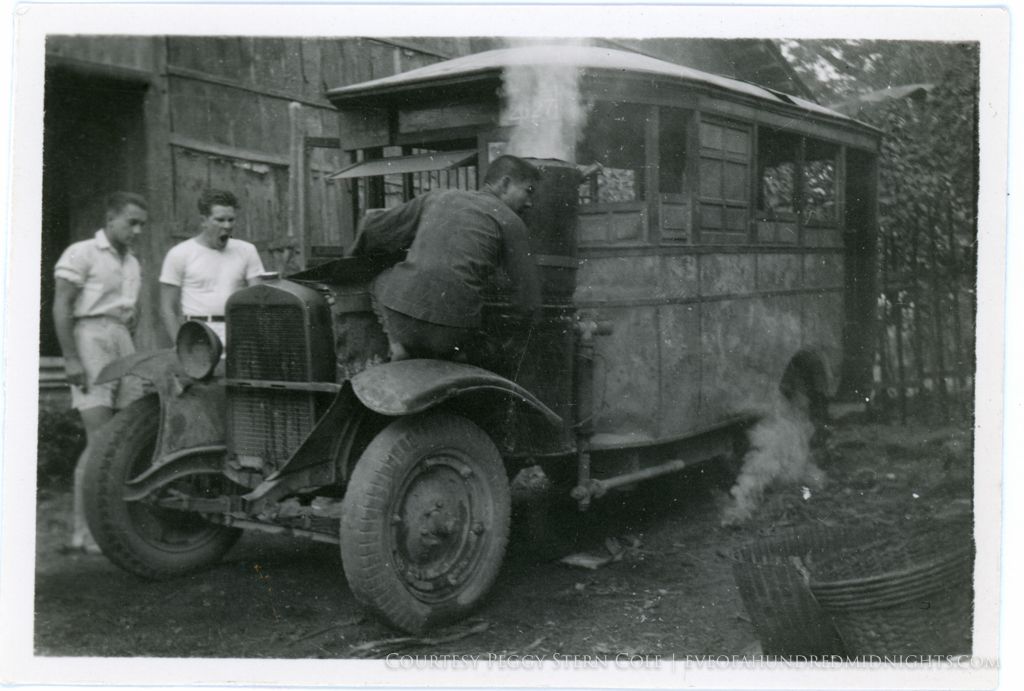

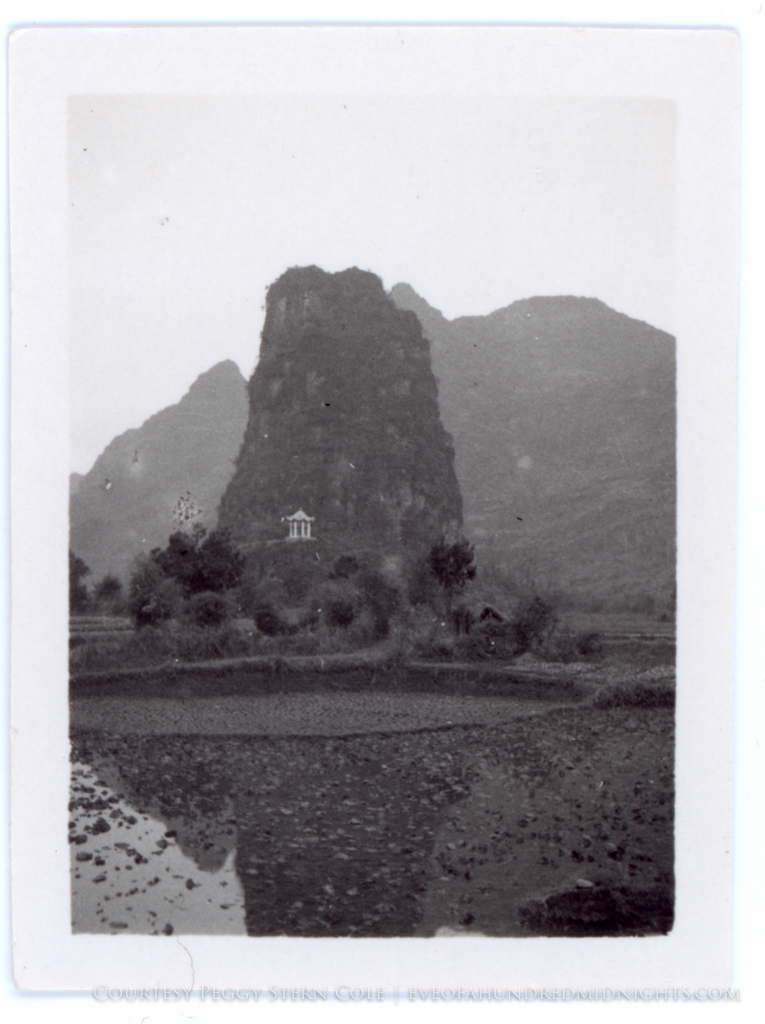

This volume offers a chance to revisit some of these stories. Though Melville Jacoby worked primarily as a writer, he rarely went anywhere without a camera. The images he made over the course of his time in Asia reflect increasing comfort behind the lens. After closely examining thousands of his prints and negatives and other related collections, I’ve selected an assortment of pictures that I believe convey a sense of the world he and millions of people whose lives he chronicled experienced.

The images Mel captured reflect increasingly intimate portraits of China and its neighbors, even in their most dire moments. Candid depictions of everyday life seem ever more natural over time, though occasionally Mel’s lens reflects faces frozen in discomfort under his gaze. In some images, Chungkingers pause amid piles of rubble and chaos-filled streets — sometimes seemingly while racing to or from a barrage of bombs — to gawk at the westerner stopping to take their pictures amid the peril. It’s never quite clear whether they’re bothered, or even offended, by his presence, if other concerns have furrowed their brows, or if expressions that appear frozen for eternity as troubled looks were in fact transitory moments that passed as quickly as the shutter’s snap.

This is an imperfect and unbalanced collection. Like any storyteller’s, visual or otherwise, Mel’s career — and his eye — evolved. Hence: “A Journalist’s Glimpses of a Continent at War.” Would that Mel had taken as many pictures of Japan when he visited it at the outset of the war as he would in Chungking three years later. I wish I didn’t have to wonder which subjects Mel simply overlooked and which he elided out of fear of losing tenuous employment. It will remain a mystery what images from Southeast Asia might have survived had Mel’s dogged work not made him wary after death threats and an arrest outside Haiphong on espionage charges. And, of course, we’ll never know what was lost on New Year’s Eve, 1941, when Japanese forces approached Manila, leaving Mel and his Time Inc. colleague Carl Mydans with no option but to incinerate their reporting material in a hotel basement. For that matter, even though Mel provided the first pictures most Americans saw of their countrymen’s desperate fighting on the Philippines’ Bataan peninsula and of those soldiers’ stubborn resistance on Corregidor, I wish I could see what images of these and other embattled places he lost during his final perilous escape from the Philippines when he was forced to ditch everything but what he could carry.

War Map of China

Residents of Chungking study a large public map of China with information about aerial battles, bombing raids, and other updates about the war with Japan

Soldiers marching

A column of Chinese soldiers parade through a city street somewhere in China, likely Chungking, circa 1940-1941

Woman cooking in Chungking

A woman prepares blocks of tofu while other food cooks at a stall in Chungking

While I am originally a writer and reporter, the time I’ve spent examining Mel’s life and work sparked a personal interest in photography, archival work and preservation. I mention this to emphasize that while I’ve done my best to faithfully capture the originality of the images presented here, I have little prior professional experience in these fields. I have digitally removed dust and scratch marks introduced while scanning images, slightly adjusted tone where necessary for some images, and, with a handful, made minor crops that don’t change what I believe were the pictures’ intended composition or content. I’ve clearly labeled the few instances where I’ve made any significant adjustments. I took great care to remain faithful to each original and I think I was successful in doing so, but I also think it’s essential that I note that these are not totally untouched images.

What you see here is an incomplete record, as is any history or other collection of images and text. My understanding of Mel and the world he witnessed comes from examining his work, his correspondence, and what personal ephemera survived decades of travel, war, relocation, death and everyday life. I managed to glean invaluable perspective through conversations with a few people who met Mel and survived long enough for me to meet them. I augmented my knowledge of the context in which he worked (and the context that situates this collection) with primary sources from dozens of archival collections from journalists, academics, soldiers, sailors, politicians, and business people who grew up, lived, worked, loved or fought throughout Asia. That context was then deepened by readings from and discussions with countless other authors, historians, scholars and storytellers.

Soldiers with Stretchers

Chinese soldiers gather with stretchers on a rubble-strewn Chungking street after an air raid circa 1940-1941

Sisters on steps

China’s powerful “Soong Sisters,” Soong Mayling, Soong Ai-ling, and Soong Chingling during a tour of Chungking in April, 1940. The tour was part of a heavily publicized reunion of the sisters aimed at boosting Chinese morale during the war and cultivating sympathy from potential allies, including the United States

I cannot with complete certainty claim what any one image in this collection depicts, nor can I answer the countless questions each provokes. What was Mel trying to capture with a given photo? What moment had he hoped to record when he clicked the shutter button? Who were the people in front of his lens? Where were the places they occupied? Why were people in some images sifting through rubble or running from flames in others? Why were faces in some pictures full of tears and others brightened by smiles? What might have been left out of a frame? Where can such omissions be traced to Mel’s own actions as a photographer, and which can be explained by the haste and danger of war? What about entire images that might have been omitted? Which were left out because of Mel’s own decisions and which omissions can I attribute to the simple havoc wrought upon memory and history by the passing of years?

Multiple lenses filter my understanding of World War II in general and the war in Asia specifically. These filters include Mel’s own decision-making about what images and events to record as well as the time that passed between these decisions and my first learning of Mel’s story decades later. I mention these layers of filtration neither to excuse mistakes nor evade scrutiny, but to acknowledge that I don’t intend this collection as a definitive record of either the war or Mel’s career. Instead, I hope this project serves to prompt discussion and examination.

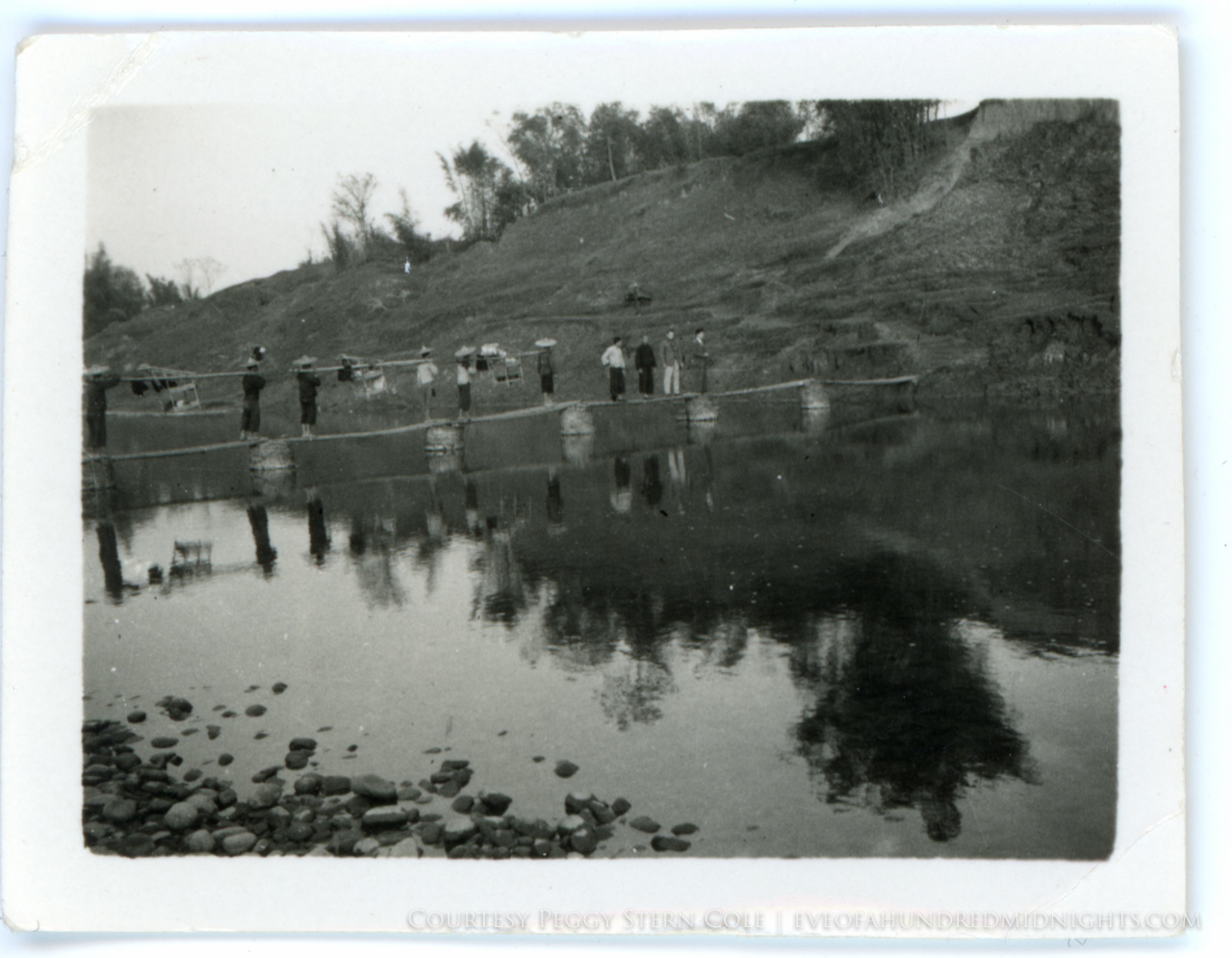

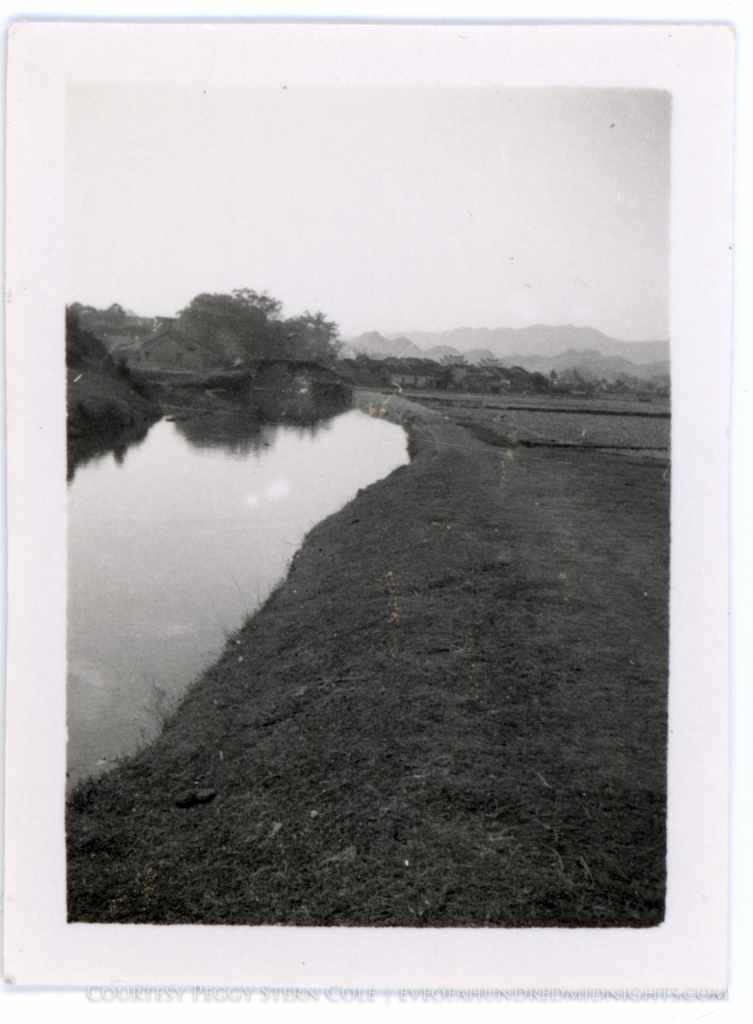

Hanoi canal

Residents of Hanoi, Tonkin, French Indochina (present-day Vietnam) walk along a dirt road next to a canal in the fall of 1940

I’ve been able to confirm what some of these images depict by triangulating Mel’s work with other sources, but some were more difficult to assess. Where I can confidently identify someone, or some place, or some moment, I have done so. Where I have a strong hunch of how to label an image, yet lack certainty, I have so indicated. Other images will be left to interpretation, but I included them because they remain intrinsically powerful. Perhaps you’ll wonder, for example, why sorrow seems to shadow some faces, while others betray a joy that seems impossible among all the destruction and horror. Maybe the way moments of serenity seem to persist even as tumult surrounds people will remind you of similar dichotomies in your own life. Perhaps there will be emotions on some of these faces with which you can identify, as I have many times.

Japanese tank in Hanoi

Onlookers watch a Japanese tank drive through Hanoi in the fall of 1940. After briefly resisting Japan’s efforts to move troops into French Indochina (present-day Vietnam, Laos, and Cambodia), French colonial forces controlled by the Vichy regime acceded to Japanese pressure. Following its signing of the Tripartite Pact with Germany and Italy, Japan moved thousands of troops into Indochina to cut off China’s access to munitions and other supplies

Flower seller in Hanoi

A vendor at a flower stall in Hanoi looks at a bouquet of light-colored flowers. Fall, 1940

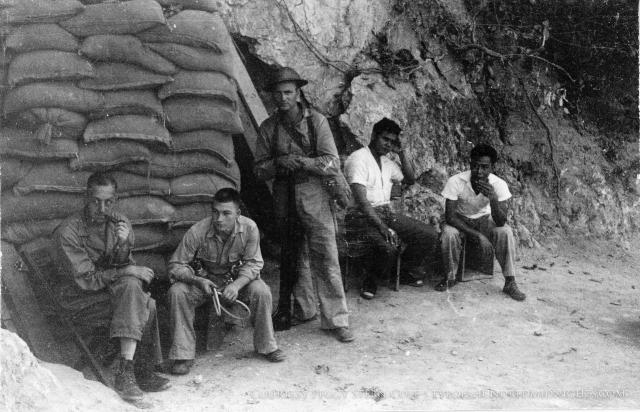

Guerrilla with rifle

A man in local attire poses with a rifle on a bridge somewhere in French Indochina, likely near the Mekong River along the border of Laos and Thailand in December, 1940

French soldiers marching with rifles

French soldiers march with service rifles slung over their shoulders after a skirmish with Japanese troops near the town of Langson at the border of French Indochina and China in September 1940

Ultimately, I hope this collection reignites interest in a period and region worthy of deeper, sustained, and expansive discussion. We live in an an era when, I believe, we all would benefit from reflecting on history. Perhaps this collection will also prompt readers to think about stories in their own worlds that remain untold or under-appreciated, and to reflect upon how our past provides perspective on our present and informs our future.

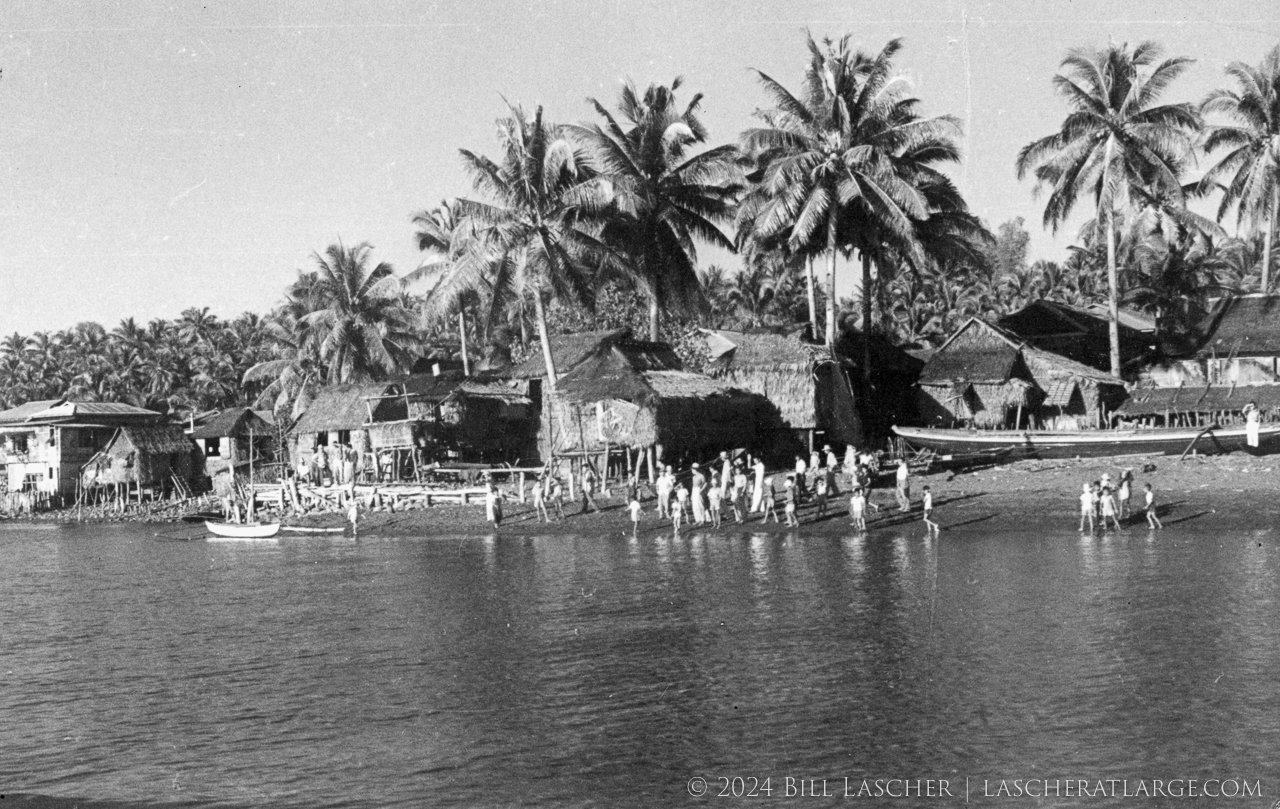

Philippine villagers on the shore

Residents of a village somewhere in the Philippines (likely Pola, Mindoro Oriental) watch from a beach as passengers of the freighter Princessa de Cebu escaping from the fortified island of Corregidor sail to shore. Among those escapees were Mel and Annalee Jacoby

Our contemporary world often feels fraught with hostility, fear, and tragedy. Sometimes I think the shadows darkening our time are akin to those that roiled Mel’s. Ideally, this volume will help illuminate a corner of the world as it was, as it is, and as it could be. There are others who can more precisely describe and interpret what happened in Asia (and elsewhere) during the period examined in this volume. This work admittedly interprets a recollection that has passed through three generations of my family’s memory and has been informed by my own professional experience as a journalist. It is not a removed, impersonal analysis. Even if it were, I didn’t experience the war, nor do I have direct connections to the cultures examined in this volume or the people who did.

Mel and his colleagues strived to accurately cover the war despite real threats and dangers. He risked everything to continue telling this story, he understood that doing so required professionalism, and he knew that expertise mattered because it strengthened value of the reports and images he and his peers recorded.

Aware of that intention as well as my own limitations, I have taken care to fairly and truthfully present these images in order to maintain that value. We must still fight to keep the story Mel helped tell visible and to retell it, even imperfectly, lest we risk repeating its darkest chapters.

Bill Lascher

September, 2023

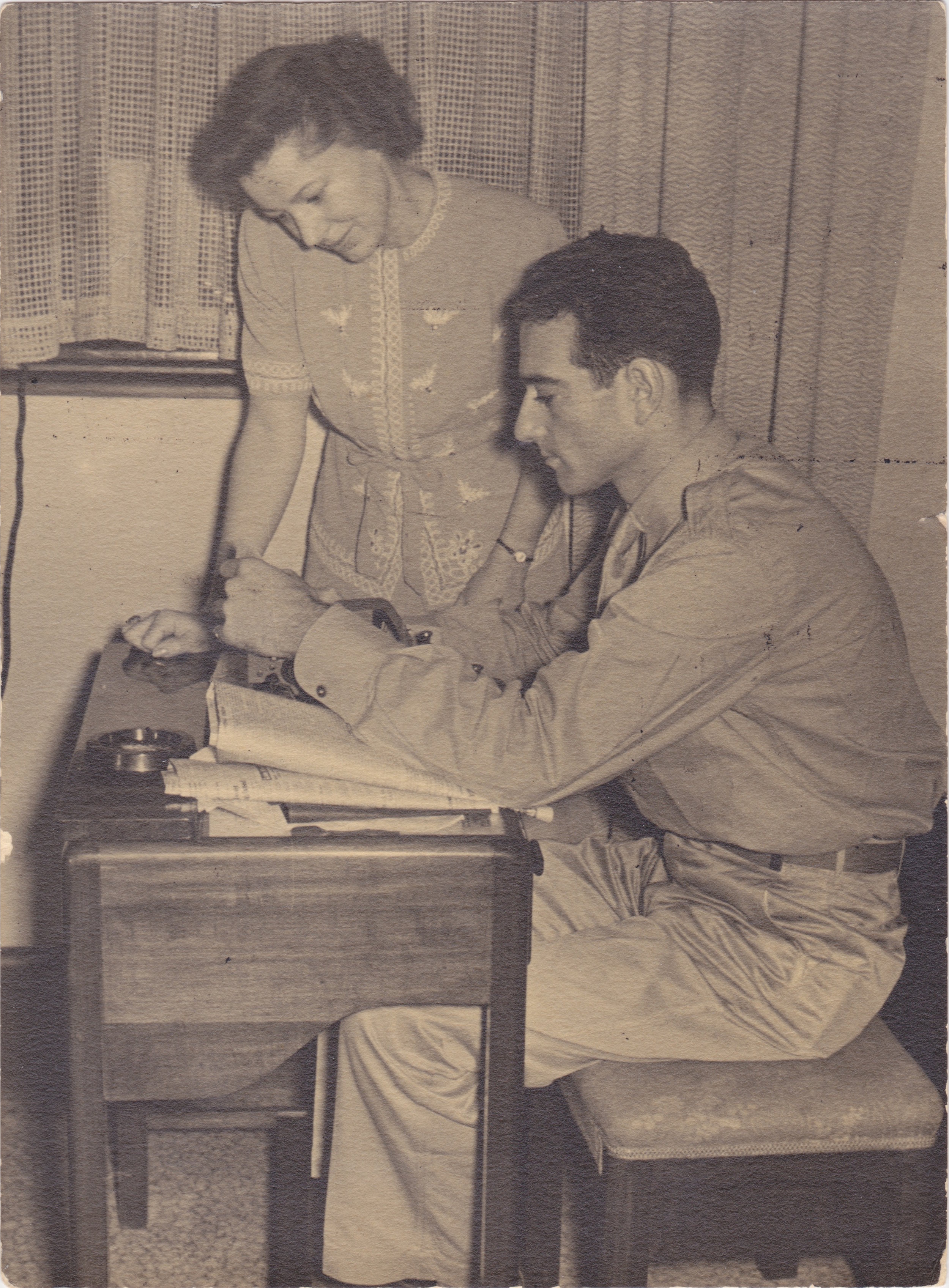

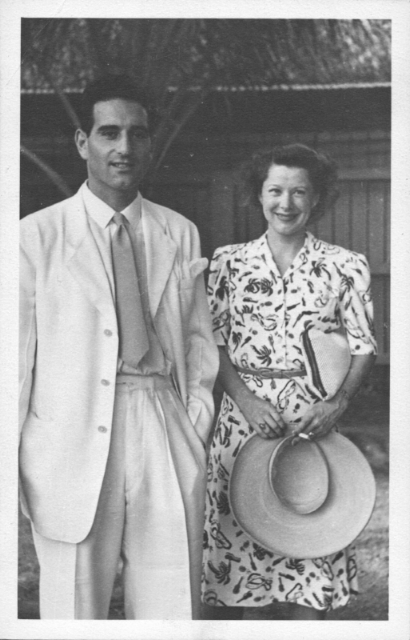

Mel and Annalee in Uniform

Melville and Annalee Jacoby sitting together in a blacked-out hotel room somewhere in Australia (likely Menzies Hotel in Melbourne), April 1942, shortly after their escape from the Philippines aboard a blockade runner. Each wears uniforms issued by the U.S. Army to accredited correspondents, as indicated by the embroidered “C” visible on Mel’s shoulder. Annalee, then a contributor to Liberty Magazine, was the first woman accredited by the army in the Pacific Theater. Mel was Time Magazine’s Far East Bureau Chief.

Infamy in Manila

Today is the anniversary of the attacks on Pearl Harbor and the Philippines that brought the United States into World War II as a combatant. In Manila, reporters Melville Jacoby, Annalee Whitmore Jacoby, and Carl Mydans sprung into action to cover the conflict. Here's an excerpt from the book Eve of a Hundred Midnights, by Bill Lascher and published by William Morrow, describing their experience of that harrowing first day.

Newlywed reporters Melville and Annalee Jacoby at work together during the outset of World War II. Photo Courtesy Peggy S. Cole.

Communication lines with Hong Kong were silent.

Radios tuned to Bangkok broadcasts received dead air.

Wireless communications with the United States carried only static.

The streets outside the Bay View were empty.

The morning of December 8, 1941, was deceptively quiet. Then the phone rang.

It was Carl Mydans. Pearl Harbor had been bombed. A newspaper slipped under Carl’s door declared the news in bold headlines. Melville Jacoby didn’t believe his colleague, so he looked at his own paper and “saw some screwy headline that had nothing to do with Honolulu.”

Still doubtful about what Carl had told him, Mel went back to bed, but he couldn’t fall back asleep.

He called Clark Lee, who confirmed the news.

There had been ever-more-frequent Japanese flybys of the Philippines in the preceding days, but still, the news was a shock. “We’d known about the Japanese flights, all the other signs, but we didn’t quite believe it even out there,” Mel wrote.

While Mel was on the phone with Clark there was a knock at his door. He hung up and heard another knock, heavy and insistent. Mel found Carl standing outside the hotel room door, already dressed and ready to head into the city.

That World War II would be fought, and won, in the skies was clear early in the conflict. Though Japan delivered its first blows at Pearl Harbor, more than 6,000 miles across the Pacific from the Philippines, it followed its opening act with devastating raids on two airfields—Clark and Nichols Fields—in the Philippines. Two squadrons of B-17 bombers, dozens of P-40 fighters, and other planes were destroyed, eliminating much of the matériel that had been sent at General Douglas MacArthur’s request.

Despite the news of the attacks in Hawaii nine hours earlier, the planes had been left in the open while their pilots ate lunch nearby. Flyers didn’t receive warnings of the approaching Japanese planes until they were almost overhead.

“By noon the first day, pilots were waiting impatiently on Clark field for take-off orders to bomb Formosa,” Annalee Jacoby wrote, referring to the Japanese-occupied island now known as Taiwan. “Our first offensive action had to wait for word from Washington — definite declaration of war. Engines were warmed up; pilots leaned against the few planes and ate hot dogs.”

Twenty minutes later, without warning, Annalee wrote, fifty- four enemy bombers arrived, delivering a brazen, devastating raid on Clark Field that crippled an already underprepared American garrison.

These raids sparked a decades-long debate about who was responsible for the blunder, but whoever should be blamed, the United States lost fully half of its air capacity in the Philippines in this one devastating first day of the war.

“MacArthur’s men wanted to fight—but most of all they wanted something to fight with,” Mel wrote in a flurry of cables he sent Time following the war’s commencement and the air- fields’ decimation. Unfounded rumors of convoys and flights of P-40s coming to join the fight began almost as soon as the attacks subsided. They would not cease for months.

On that morning, Manila’s Ermita neighborhood was quiet. Mel arranged a car for the Time employees to share. Together they raced up Dewey Boulevard, to Intramuros, the walled old- town district that had been Spain’s stronghold during its 300- year occupation. When they reached the U.S. Army Forces in the Far East (USAFFE) headquarters at 1 Calle Victoria, they found MacArthur’s driver, who had arrived early in the morn- ing, asleep in his car.

“Headquarters was alive and asleep at the same time,” Mel wrote. MacArthur’s staff was weary-eyed but busy as they girded for war. Within hours, helmeted officers carrying gas masks on their hips raced back and forth across the stone- walled headquarters, stopping only briefly to gulp down coffee and sandwiches. The general himself was his usual bounding self, striding through the headquarters as staff and other wit- nesses confirmed reports of attacks throughout the Philippines. Mel and Carl were concerned about their jobs. Would wartime censorship clamp down on their reporting?

“The whole picture seemed about as unreal to USAFFE men as it did to us,” Mel later wrote. “We couldn’t believe it, and MacArthur’s staff had hoped the Japanese would hold off at least another month or so, giving us time to get another convoy or two in with the rest of the stuff on order.”

This hesitation, of course, was partly to blame for the devastation that occurred that day and the unsettled footing with which American forces fought during the brutal months to come.

Meanwhile, deep-seated racial prejudices kept many Americans from believing that Japan was capable of carrying out the attacks.

“Those days were eye-openers to many an American who had read Japanese threats in the newspapers with too many grains of salt tossed in,” Mel wrote. “They still couldn’t believe the yellow man could be that good. It must be Germans; that was all everyone kept saying. We were just beginning to pay for years of unpreparedness. The shout ‘It’s Chinese propaganda’ had suddenly lost all traces of plausibility.”

Regardless of who was to blame, U.S. forces reeled.

Manila was quiet even as chaos engulfed the headquarters, where a scrum of reporters waited for updates. Rumors flew beneath the shady trees of Dewey Boulevard, rippled up the Pasig River, and raced past the storefronts along the Escolta.

“The whole thing has busted here like one bombshell, though, as previous cables showed, the military has been alert over the week,” Mel would soon write.

As the realization of what had begun set in, Manila residents rushed through the city, withdrew cash from banks, stocked up on food, and bought as much fuel as they could before rationing was ordered. Businesses quickly transformed basements into bomb shelters. Sandbags became scarce. As would happen all over the United States, local military rounded up anyone of Japanese descent, whether they were Japanese nationals or not. The Philippines waited for war.

From Eve of a Hundred Midnights, by Bill Lascher and published by William Morrow (2016). For the story of the Jacobys' last-minute escape from the Philippines and to learn about their work as war correspondents in China and the Philippines, find Eve of a Hundred Midnights at your favorite bookseller, or order it from Indiebound, Powell's, Amazon, or Barnes & Noble.

Appreciation

Last night, April 24th, 2017, the Oregon Book Awards took place in Portland. Eve of a Hundred Midnights was nominated for the Frances Fuller Victor award for general nonfiction. While the book didn't win, it was such an honor to be chosen a finalist. Moreover, being asked to write some remarks in case I did win proved to be a wonderful opportunity to reflect on all of the people I appreciated for making this book possible. Here's what I would have said, because it's all still true.

Last night, April 24th, 2017, the Oregon Book Awards took place in Portland. Eve of a Hundred Midnights was nominated for the Frances Fuller Victor award for general nonfiction. While the book didn't win, it was such an honor to be chosen a finalist. Moreover, being asked to write some remarks in case I did win proved to be a wonderful opportunity to reflect on all of the people I appreciated for making this book possible. Here's what I would have said, because it's all still true:

Today marks the 75th anniversary of what could have been the last time my grandmother, her parents, and the rest of her family heard the voice of Melville Jacoby, my grandma's beloved oldest cousin and the subject of my book. That night three quarters of a century ago, everyone gathered around their radio listening to the March of Time, hoping to hear from Mel, a reporter who, with his wife, the journalist and former MGM screenwriter Annalee Whitmore Jacoby, had just survived a month-long escape from the Philippines, and six weeks of reporting from the front lines of Bataan and Corregidor.

Mel's broadcast failed and his family didn't get to hear his voice again. However, three quarters of a century later, thanks to my grandmother, Peggy, and her sister, Jackee, I've been able to give voice to his story. This award honors not just them, or Mel, but the people whose voices were only heard because Mel sacrificed so much as a foreign correspondent.

It's an honor to be nominated among this wonderful group of fellow writers, in part because many of them have produced work that amplifies the voices and subjects too often overlooked, marginalized or forgotten.

I would not have been able to tell this story were it not for others in my family as well, especially my mother, Wendy — my first and often shrewdest editor — her siblings, and my own siblings. Likewise, my partner, Andrea, has helped me survive every stage of this book's production and championed me even when I second-guess myself

Over the course of seven and a half years, more than half of which I spent on this book, Oregon has become my home. While today, too many ominous signs remind me of the dark world in which Mel and Annalee worked as reporters, the community I've found here in Oregon and what I like to call its "pot luck" culture are key reasons why I'm hopeful we'll all be able to survive whatever comes next. Many of those I've met here, whether writers or not, have contributed something that helped me make this book possible, and in turn, ensured that I have been able to get Mel's voice heard once again.

Into the Blackness Beyond

"We are remembering MacArthur’s men, how hard it was to finally leave, how lucky the three of us are."

On February 23, 1942, Seventy-five years ago as I write, Melville and Annalee Jacoby crossed the two-mile-wide channel between the fortress island of Corregidor and the besieged Bataan Peninsula for the last time. There, there would wait until sundown when a small inter-island freighter, the Princesa de Cebu, arrived in the channel, ready to sneak through the Japanese blockade surrounding the Philippines' largest island, Luzon. Their hope: escape to unoccupied portions of the Philippines and then, if they were lucky, find another ship through Japanese waters to allied territory. Here is the story of that night as told in the bestselling book, Eve of a Hundred Midnights:

“We sit by the side of a Bataan roadway waiting,” Mel wrote as he and Annalee absorbed their last moments on the peninsula amid a thick knot of banyan trees near the shore. “Our visions of past months of war are vivid, clouded only momentarily during this waiting by thick sheets of Bataan dust rolling off the road every time a car or truck races by. We wonder for a moment when we will return—and how.”

Finally, escape was in sight. At dusk, a launch would arrive to take the Jacobys to the Princesa de Cebu. That ship, they hoped, would then slip past enemy patrols at the mouth of Manila Bay and carry the reporters through the Philippines—possibly even farther across treacherous, Japanese-controlled sea-lanes and on to refuge in Australia, thousands of miles to the south.

Through a pair of binoculars borrowed from a soldier on the Bataan coast, Mel peered south toward Manila. He thought he could see the rising sun of the Japanese flag fluttering over the Manila Hotel, the same place where he’d had his last Christmas dinner, where Annalee had danced with Russell Brines and Clark Lee had urged Mel to flee the Philippines. He knew that Carl and Shelley were somewhere beneath that fluttering crimson-and-white banner. A reliable confidential source had told Mel that the Mydanses were among the thousands in captivity at Manila’s Santo Tomas University, which the Japanese had turned into an internment camp. However, it had been a month since that report.

That day Mel and Annalee felt as “impregnable as the mountain,” almost invincible “for the first time in this war.” Finally, they were leaving, Mel wrote, recalling people and moments from his six weeks on Corregidor and Bataan. Leaving everything. Leaving General Douglas MacArthur. Leaving the general’s trusted lieutenants, who had become their friends. Leaving the scores of men they’d met at the front whose stories had yet to be told. They were leaving all of them behind, “most of all the scared Pennsylvania soldier who ran the first time he heard [Japanese] fire but who braved machine gun fire the second time to carry his officer off the field.”

As the Jacobys walked along the tree trail, a Jeep carrying two officers skidded into the dirt. The noise and dust shook Annalee and Mel back into the moment. They stood up and greeted the officers. It was the first time Mel really registered the weariness on the faces of those fighting in Bataan. Despite the fatigue in their eyes, neither officer mentioned their exhaustion. Instead, they chatted casually, sharing rumors and battlefield legends until the soldiers finally drove off a few minutes later. Mel and Annalee again turned to thoughts more hopeful than the soldiers’ exhaustion. Like thoughts of ice cream sodas. Could they ever taste as good as they imagined?

Finally, the sun began to set. It was time.

The couple ran back toward the shore along the tree trails. One path led to the last American planes remaining in the Philippines, the rickety trainers, a couple of obsolete fighters, the P-40 so “full of holes.” The planes were hidden next to an airstrip that resembled a hiking trail more than a runway.

Mel and Annalee were barraged by memories at each turn. They passed anti-aircraft batteries, a motor pool, a machine shop, even a bakery (though one that had never had bread to bake) and a makeshift abattoir where first caribou, then mules, then even monkeys were slaughtered for the soldiers’ meals.

Across the narrow channel from Bataan, Clark Lee had finished wrapping up his own affairs on Corregidor, and now he was waiting for the Jacobys at the same dock on the island’s north side where the trio had come ashore on New Year’s Day. He did bring a typewriter, as well as a razor, a toothbrush, and a change of clothes.

The Princesa approached at dusk, slowly steaming westward. They boarded and were greeted by four British and two American civilians who had received field commissions after fleeing from Manila to Bataan. They had boarded the Princesa from a separate launch earlier. Among them was Lew Carson, a Shanghai-based executive for Reliance Motors hired by the army to help manage its motor pool, and Charles Van Landing-ham, a former banker who escaped to Bataan on a tiny sailboat on New Year’s Eve. Also a contributor to the Saturday Evening Post, Van Landingham was struck by how deceptively peaceful the green jungles of Bataan looked as he left.

“It was hard to realize that under that leafy canopy thousands of hollow-eyed, half-sick men stood by their guns, fighting on grimly in the hope that help would come before it was too late,” Van Landingham wrote.

Its lights dark, the Princesa slowly made its way into mine-laden Manila Bay. Huge searchlights on Fortuna Island scanned the sky above the island as its “ack-ack” guns—anti-aircraft artillery—fired at Japanese bombers. The darkness gave way momentarily to the glow of the guns’ tracers, which lit the passengers’ faces. Then night returned across the ship’s deck.

From Corregidor, a searchlight swept the coast in front of the Princesa. A small, fast torpedo boat appeared and led the ship through the mines, barely visible but for the path carved by its wake. The craft was skillfully piloted by Lieutenant John D. Bulkeley, who provided a few minutes of covering fire while guiding the Princesa toward the mouth of Manila Bay. Then, in a final farewell gesture, Bulkeley flashed the torpedo boat’s starboard light and roared back to Bataan, leaving nothing but darkness in his wake.

Night on the Pacific washed across the Princesa. Only the distant flash of Japanese artillery punctuated the dark. The ship’s two masts bobbed beneath what Mel’s eyes found to be a “too bright moon.” This was the same moon the soldiers on Bataan prayed would descend quickly, lest even a quick glint of its light across a shining service rifle’s barrel draw a sniper’s bullet. Now the moon cursed the Princesa. The nearby shore was dark, but everyone aboard the Princesa knew it crawled with enemy forces. They silently watched the passing islands. Each lurch of the ship tied the passengers’ stomachs in a “tight feeling.”

A crew member snapped a chicken’s neck. The reporters jumped at the bird’s sudden, loud squawk.

It was just dinner, but everyone crossed their fingers.

“Sure, we’ll make it,” someone said. “Easy.”

All three reporters rapped their fists on the wooden deck.

Nobody slept. Everyone kept watch, fearful of missing even the briefest moment of movement. Finally out of Manila Harbor, the ship maneuvered toward the southeast and crept through the darkness along Batangas, on the Luzon coast south of Manila.

Thousands of miles, countless inlets and islands, circling recon planes, even submarines and destroyers dispatched by the Philippines’ new conquerors lay between the reporters and safety in Australia. They spoke little. Instead, they reflected privately on the soldiers they had met on Corregidor and Bataan, the onslaught both places had endured, and their own good fortune so far.

“We talk very little sitting on deck now. We are remembering MacArthur’s men, how hard it was to finally leave, how lucky the three of us are. We’d gotten through the [Japanese] before,” Mel wrote. “Everything we’ve known the past two months is swallowed in blackness beyond.”

On Protest and Reporting

Today, Poynter ran a piece titled "Should journalists protest in Trump's America?" It was mostly focused on newsroom journalists. In reply, I wrote up my thoughts about how it applies to me as a freelancer.

Today, Poynter ran a piece titled "Should journalists protest in Trump's America?" This is a question I've been wrestling with as a freelancer. It was mostly focused on newsroom journalists. I posted to Facebook and tweeted, wondering how it applies to freelancers like myself. The piece's author, Katie Hawkins-Gaar, asked me to elaborate. At first I responded in tweets, but then realized I had more to say. Here's what I ended up writing.

Why is it important that I be on top of current affairs? Partially, so as I reach out to editors I can be prepared to jump into my reporting and do it well. I need to have a clear idea of what current issues are to make an effective contribution. On a more selfish level, I need to have a clearer idea of what kind of stories will more easily get an editor’s attention, not to mention that of the public.

In the meantime, I also need to report potential stories, pitch them, and wait on editors understandably harried by current circumstances to reply. How do I survive doing so with such uncertainty? How do I make a living doing that? And how do I do that if the world is changing very rapidly. If a crisis emerges, how does my more evergreen work matter?

That’s reporting. What about protest and politics? Do I let the world go by when people I care about are affected, concerned, scared, etc.? What about when I am affected? Am I affected? Probably not as much, because I’m white, straight, cis-male, college- and graduate school- educated and born in the United States. I am Jewish, but not practicing, and that’s still not (yet) as much a target. My best strength is my dedication to the craft, my skepticism, and my courage to tell stories even if people don’t want to hear them. But, again, I have to be able to survive telling them. It, sadly, often comes to economics, which are often made shakier by political uncertainty. So do I then work on more anodyne material while watching the world go by? Isn’t that just shutting my ears? Wouldn’t that just be isolationism in a different form?

After all, my first book is all about reporters who risked their lives and livelihoods in a troubled time to bring stories to the public that were being inadequately covered. My central subject — Melville Jacoby — was writing about devastating, daily air raids in China that were killing thousands. He was writing about brutal conditions in Shanghai and about the march toward war in what was then French Indochina. His master’s thesis was all about how the U.S. public wasn’t paying attention the war between China and Japan and what that portended for them. He knew what happened there mattered here, and vice versa, so he was driven to tell such stories. Then he reported on the totally under-resourced defense of the Philippines, and sent home the first photos the U.S. saw of the absolutely savage conditions U.S. and Filipino troops endured in Bataan.

I mention all this not because I want to raise heads about my book. I mention it because journalists are still doing this kind of work, still not being listened to, and still often dying because of their work. Seventy-five years later, journalists are telling us about civilians dying in military strikes, about coming conflicts and uncertainty, about corruption, about tone-deaf foreign policy. As a journalist, my form of protest, if I have one, is, in part, amplifying these reporters, and in part, joining them. Not letting the line go quiet.

And I do wonder, in this time, how do I do justice to the subject I spent so much time with? Mel, Annalee, and their friends and colleagues were people who had marks on their heads for their reporting, who fled besieged islands in the dead of night to get the story out. Me? I’m at home reading Twitter, trying to figure out where and how to jump in and contribute when my portfolio is, well, not stale, but, about such specific subjects it seems disconnected from what’s happening. What editor wants to take the risk on that at a time when they need to be very careful about the professionalism of their contributors, to know that they can trust the credibility of their reporting?

I guess this doesn’t answer the question of what and how I protest as a freelancer, but the thing is, I can’t afford to not think them. I don’t know any other way to operate. How do I contribute now? Lately I’ve thought the ideal is joining a news organization, becoming a stringer for a few publications, or becoming a regular contributor to a few outlets, but with freelancing, even in a time of protest, it still comes back to how do I survive while doing so? I always think I can best help society by reporting well, but where do I turn to be able to do that? Normally, I’d say my community, but if some of my community — those who aren’t reporters — are out in the streets protesting or at home making calls to representatives, and the rest — those who are reporters — are pushed to the max doing their own reporting, what’s left as a backstop or a network for me?

75 Years Ago, When War Seemed a Million Miles Away

75 years ago, today, Pearl Harbor was on the horizon, but for one couple in Manila, war briefly felt a million miles away.

Seventy-five years ago, today, with the United States and Japan on the brink of war, Time Magazine correspondent Melville Jacoby married the former Annalee Whitmore, a former MGM scriptwriter who had been managing publicity for an aid organization known as United China Relief. The following excerpt from Eve of a Hundred Midnights (William Morrow, 2016) describes the moment Annalee arrived in Manila from Chungking, the wartime capital of China, and Mel whisked her off to their wedding. Pick up the book from your favorite retailer to find out how Mel and Annalee's paths crossed, and what happened when war broke out just two weeks after their wedding.

From the edge of Pan-Am’s facilities along the southern arc of Manila Bay near the Cavite shipyard, Mel watched a Boeing 314 cross the sky. It was Monday, November 24, 1941, just three days before Thanksgiving.

Annalee was on the plane. As it landed she spotted Mel at the water’s edge, clad in a gleaming white suit, white shirt, and yellow tie.

“I could see him when the plane landed in the water, and it seemed like hours until they pulled it up onto the beach,” Annalee later wrote to Mel’s parents.

Finally, the Clipper’s pilot cut the aircraft’s engines. The plane coasted the last few feet to the dock, where its passengers disembarked. Annalee barely had time to say anything to her fiancé. After they embraced, Mel ushered her to a waiting car, which drove the ten miles from Cavite to Manila, turned right off Dewey Boulevard onto Padre Faura, then stopped at the Union Church chapel a couple of blocks away. Mel strode confidently up to the church, while Annalee, wearing a white nylon dress printed with palm trees, ukuleles, pineapples, and leis in green, yellow, and red, linked her arm in his, smiling widely, a broad-brimmed yellow hat tucked under her other arm. For a couple who never expected romance, it was as dreamlike as any fairy tale.

“It was just like I’d always hoped it would be,” Annalee wrote.

Carl and Shelley Mydans were there, as well as Allan Michie (a Time reporter about to transfer to England, Michie was also the author of Their Finest Hour) and the Reverend Walter Brooks Foley. As soon as the couple arrived, the small pro- cession gathered in an intimate reception room off the chapel decorated with white flowers and green drapes. Carl served as Mel’s best man; Shelley was Annalee’s matron of honor.

Reverend Foley performed the modest ceremony. Mel had always dreaded large, formal weddings. He had looked for a justice of the peace to officiate, but most of the ones he found spoke little English and held ceremonies in nipa huts—small stilt houses with bamboo walls and thatched roofs made from local leaves.

“The morning I came he found Reverend Foley, who was a short blond near-sighted angel, full of extravagant plans for choir chorales and processionals and borrowed bride giver-awayers,” Annalee wrote.

Annalee may not have wanted a big to-do or an ostentatious ring, but she clearly couldn’t restrain her delight at the occasion itself. Her smile did not subside throughout the ceremony. Her hands gently clasped Mel’s as they exchanged vows, and she looked intently at her husband, her eyes grinning and warm. For his part, Mel couldn’t mask the pride on his face, nor his joy.

Within an hour of Annalee’s landing, she and Mel were married. After their wedding, they wrote letters to their families. In one, Annalee insisted to Mel’s parents that she didn’t go to China to marry Mel, but she “couldn’t think of a better reason” to have gone.

The celebration continued at the Bay View Hotel, just a few blocks away. Gathered in the lobby were many of the couple’s friends who had also transferred to Manila from Chungking, as well as others Mel had met since arriving. Those who couldn’t be there sent their congratulations. Everyone, from Annalee’s colleagues at MGM to Henry and Clare Boothe Luce, to all the Press Hostel residents, to the entire staff of XGOY (which also aired a brief item about the marriage), sent their good wishes.

“General MacArthur about knocked me over the other p.m. congratulating me,” Mel wrote. “Admiral [Thomas] Hart’s staff nearly shook my hand off.”

There was a portable phonograph setting the tune with jazz standards and popular big band recordings. In between songs, the newlyweds ducked into a corner of the lobby where they took turns placing long-distance phone calls to their parents in Los Angeles and Maryland. And then they danced into the night. War was on the horizon and could arrive any day, but that evening it could have been a million miles away.

To Tell this World's Stories

Today I drive to one of Oregon's many red counties to read a story about a man who sacrificed everything to report on a besieged world.

Today I drive to one of Oregon's many red counties to read a story about a man who sacrificed everything to report on a besieged world.

I will think deeply about how he willingly and repeatedly went toward danger and discomfort when others stayed where it was safe, because he could, and he knew it was his responsibility to bring a story of how the world really was to a public that didn't seem to care, to a public that only seemed to want to hear what they thought mattered to them, even though he knew all this mattered to them. Even when given the chance to work in a safe job back home at a remove with better pay, chose a war zone. He, like many journalists today who we should value so much more, sacrificed his livelihood, and his life so that we could know the world.

To be clear, what I am doing is not the discomfort or sacrifice I reference, but what we must do as reporters will be on my mind as I read.

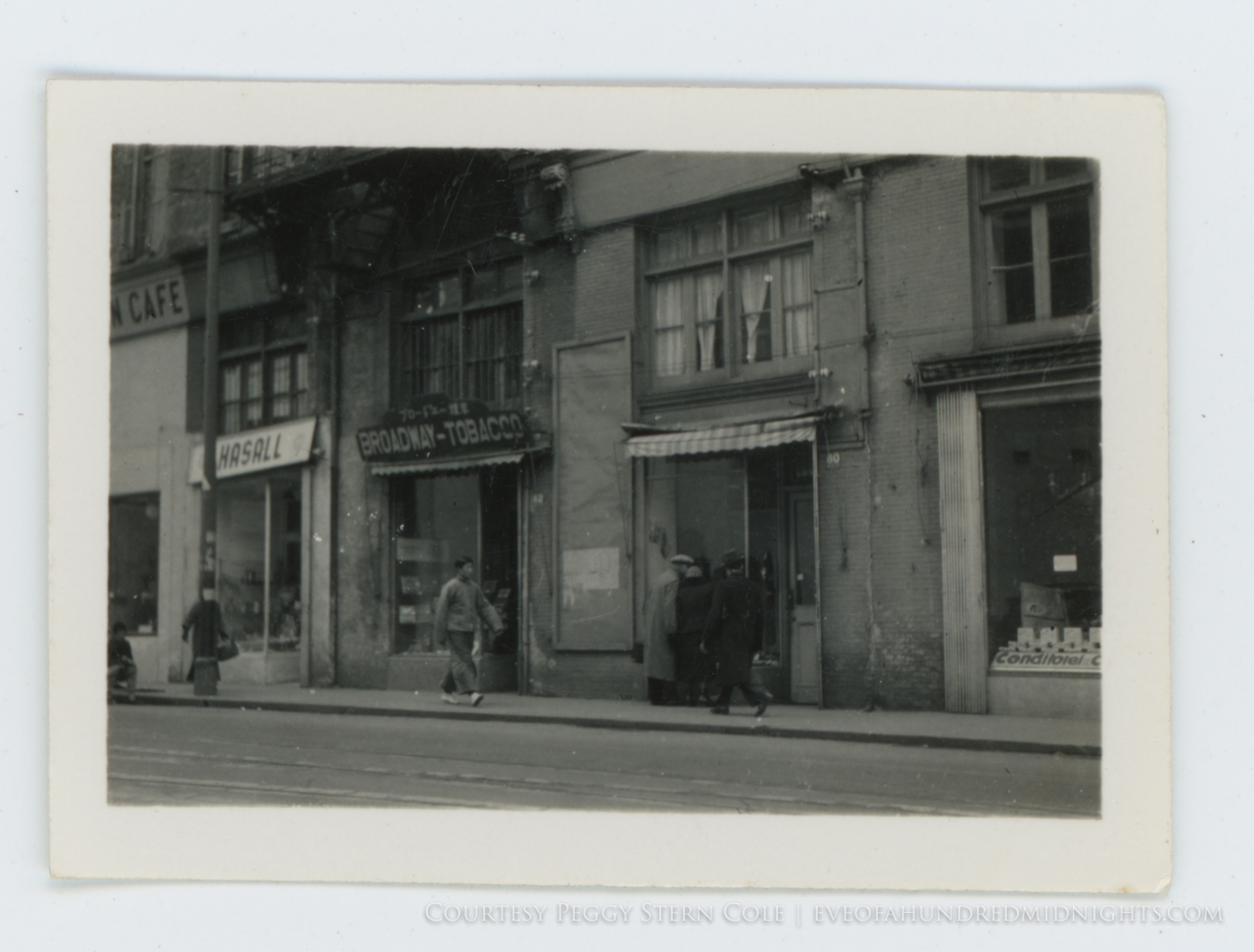

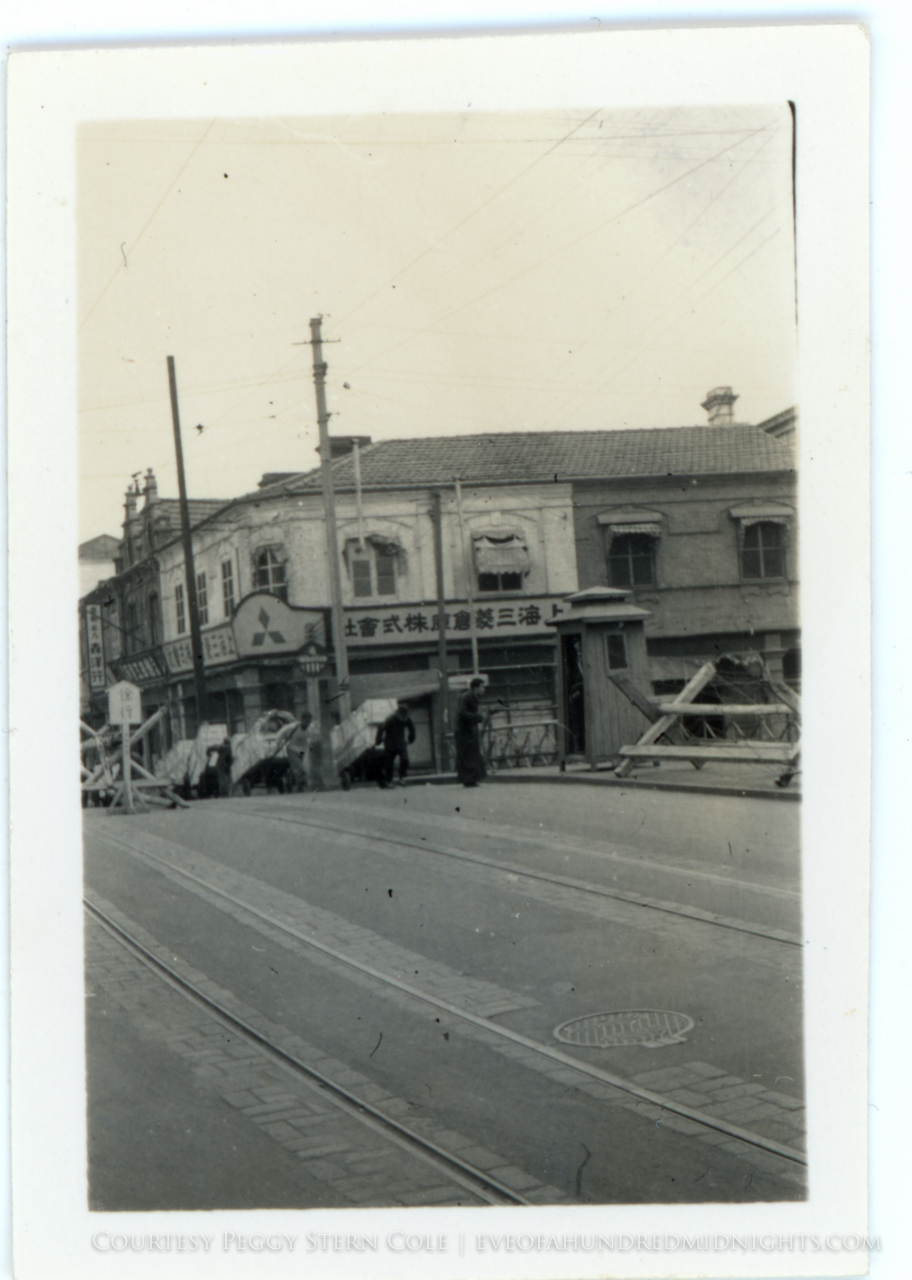

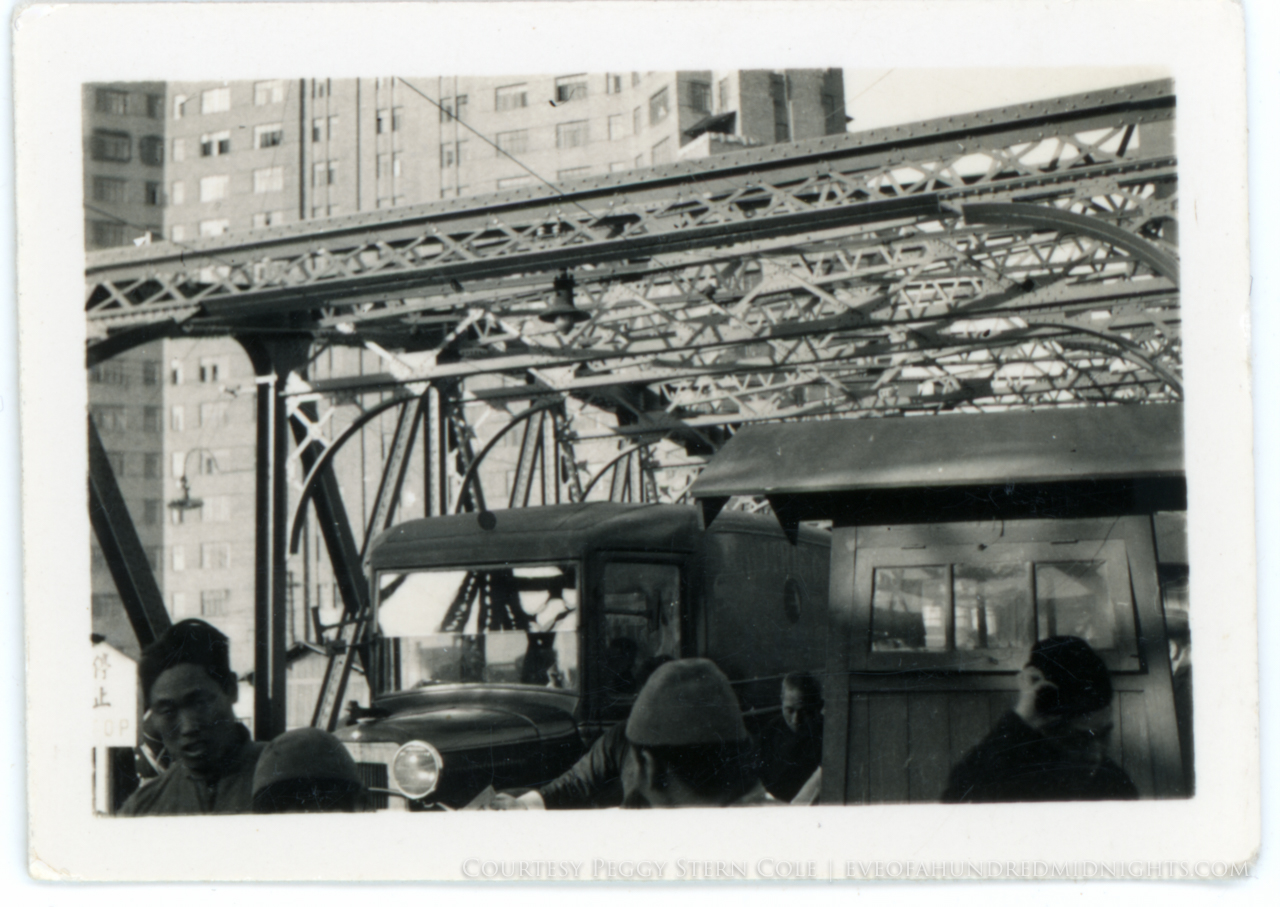

Shanghai Takes it On the Chin

“I hate to see the rich kids in the cabarets, I hate to see the refugees, I hate to see the lousy foreigners in Packards and minks. Lots of money is being made now on the market and in business—but the Chinese peasant is taking it on the proverbial chin.”

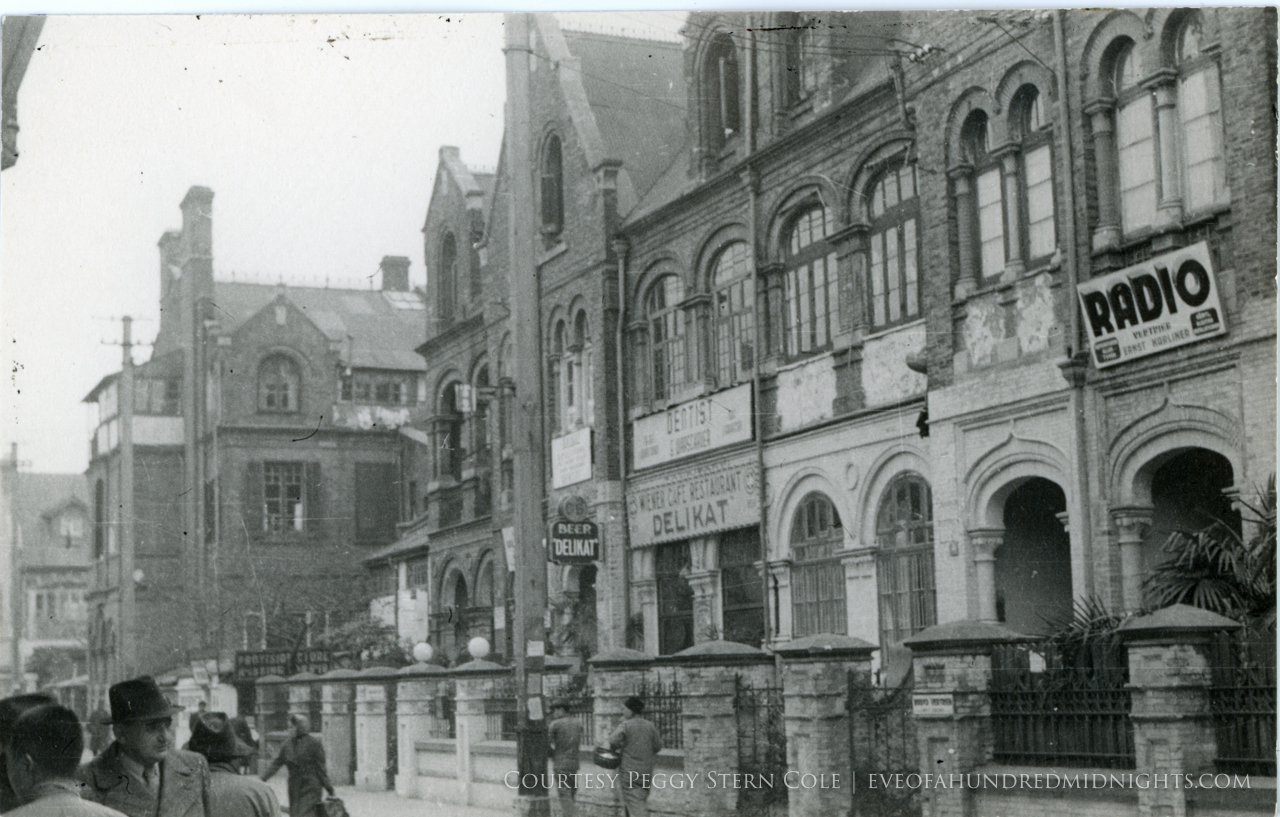

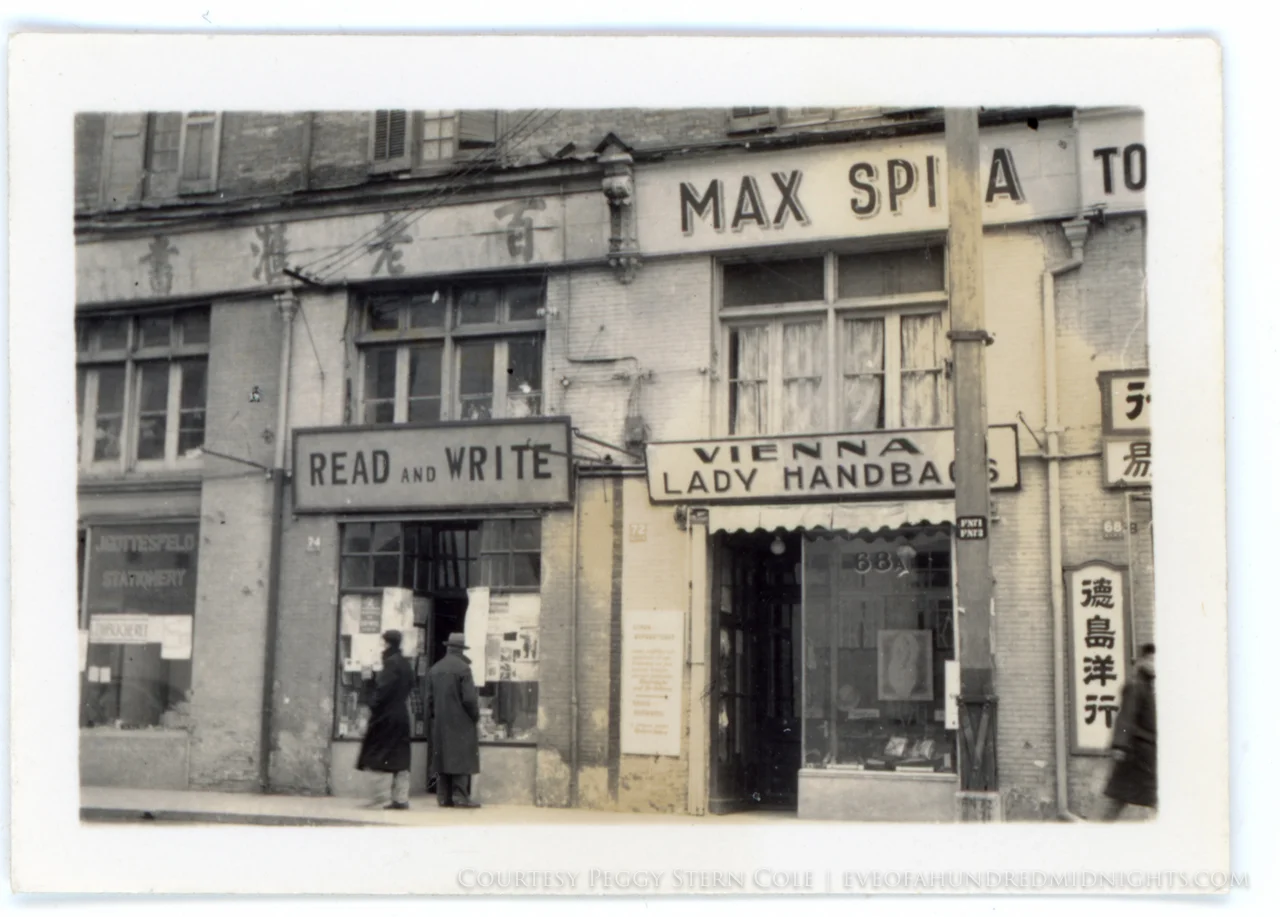

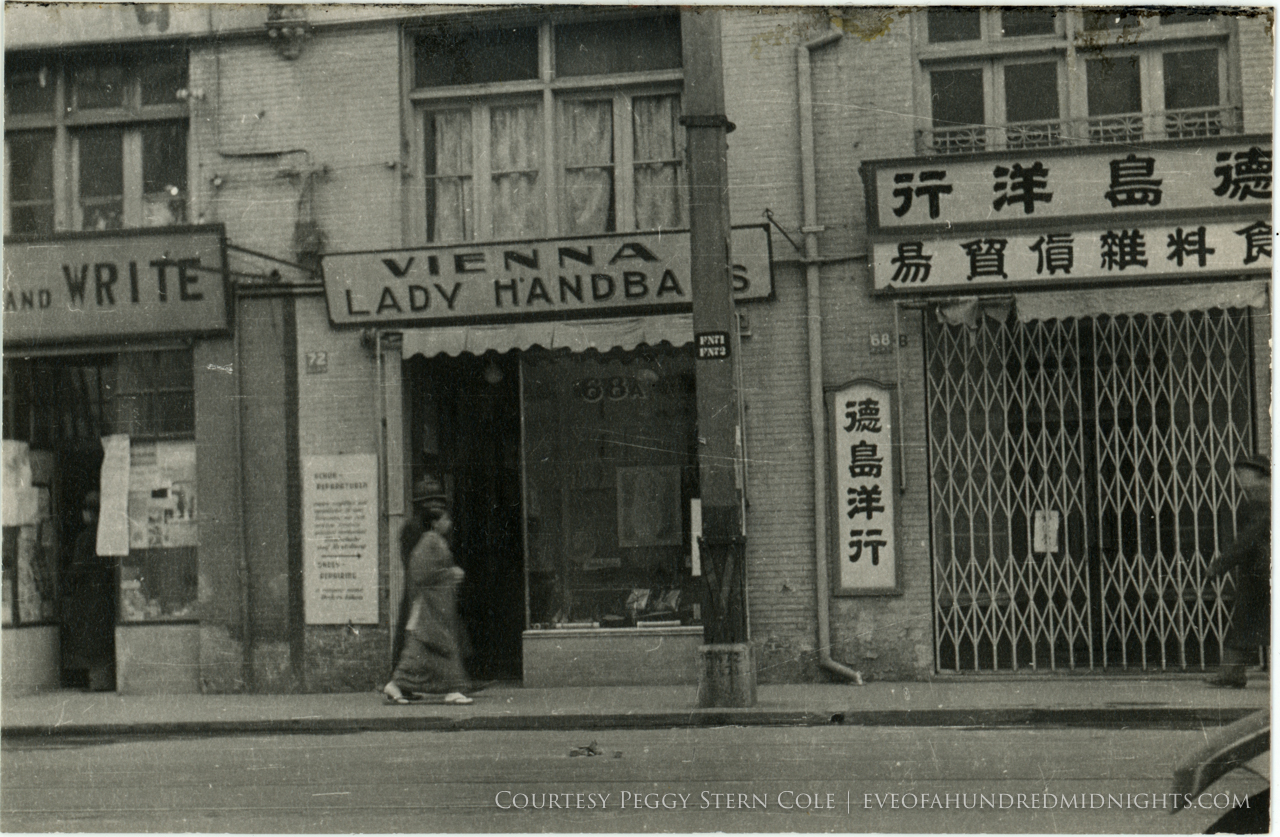

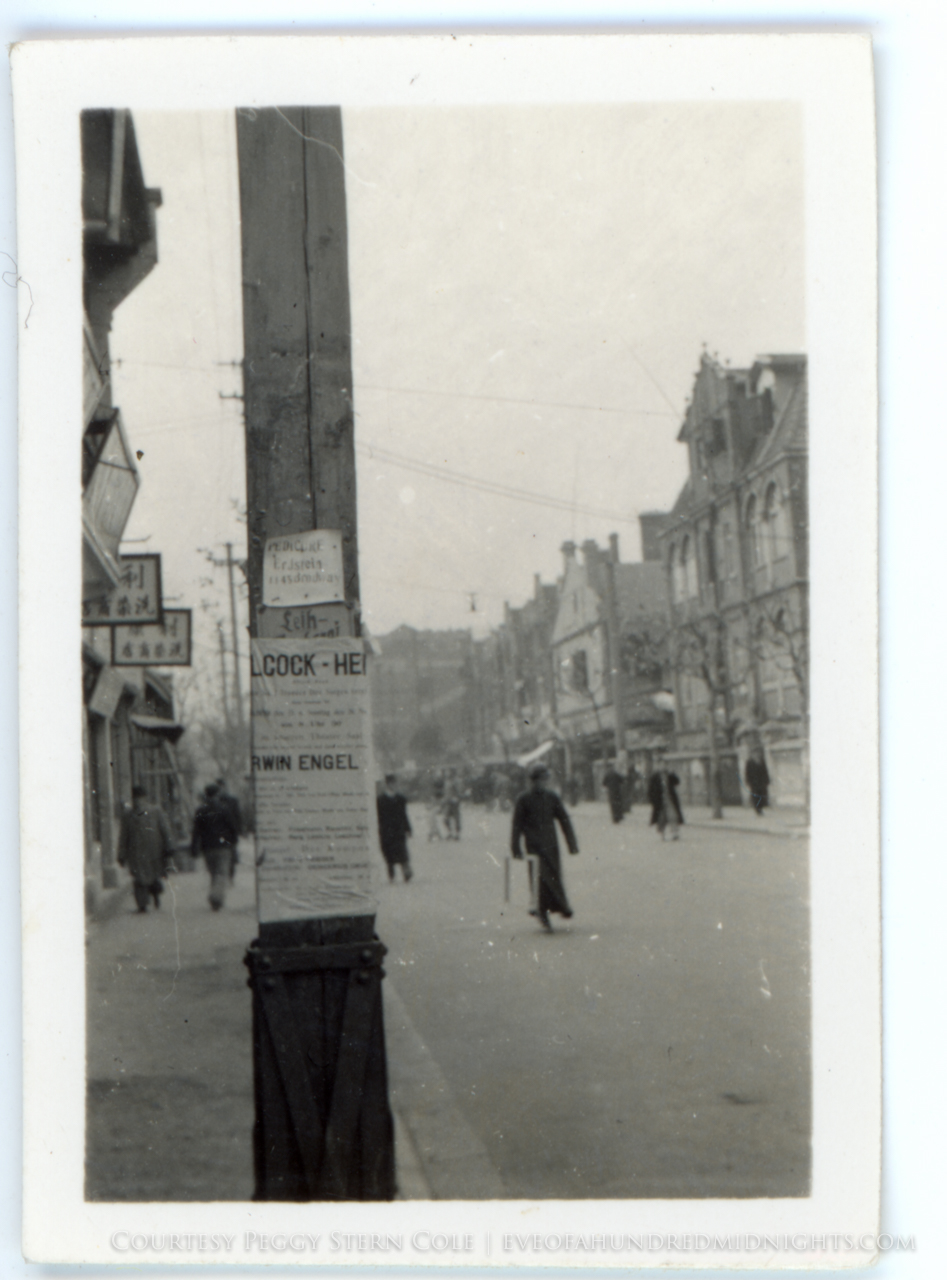

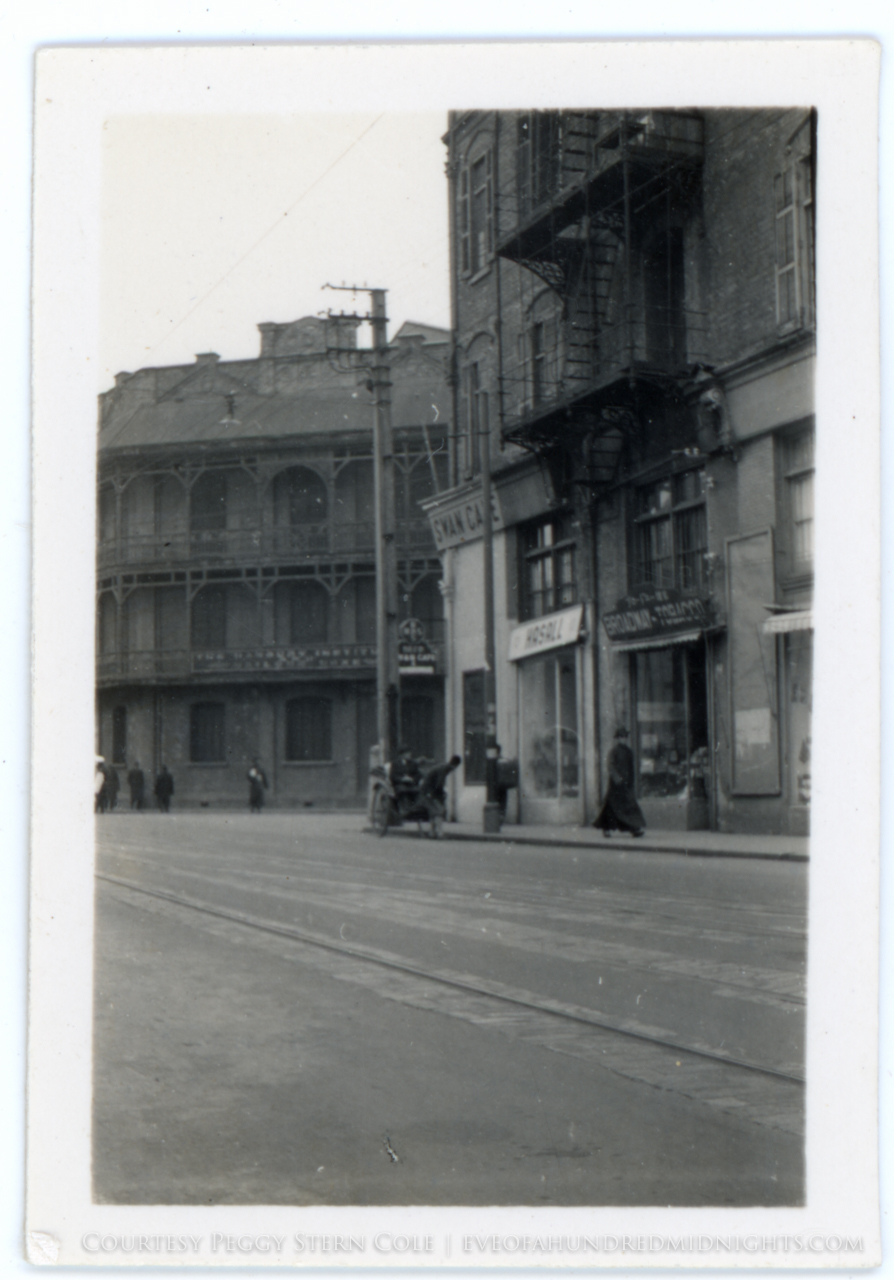

In November, 1939, Melville Jacoby arrived in Shanghai, China. Having just earned his master's degree in journalism from Stanford, Mel returned to China two years after studying there as an exchange student. Mel arrived in Shanghai with no work, but a raft of letters of recommendation from newsmen and scholars who had been impressed by a presentation Mel made of his research into California newspapers' coverage of China and Japan in the run-up to a war that had been raging since the summer of 1937, just as Mel completed his exchange year. As Mel hunted for work in Shanghai, he discovered a city packed with thousands of Jewish refugees who'd been turned away by every other port on Earth. It was a city occupied by Japan, though still nominally internationally-controlled, as it had been for decades. Here are some selections of how the city looked to Mel:

Here's how I described Mel's impression of Shanghai in Eve of a Hundred Midnights:

“But if you aren’t British or French or American or if your country hasn’t got enough gunboats it isn’t so international,” Mel wrote, referring to the many foreigners who came to Shanghai butwere not nationals of countries that enjoyed extraterritorial powers. Paradoxically, among the most disenfranchised populations in Shanghai were Chinese nationals. And though Shanghai maintained much of its international identity when Mel arrived in 1939, in the two years since the Battle of Shanghai, Japan had consolidated power there and grown increasingly belligerent toward both the Chinese and Westerners.

“The Western world is being squeezed out of China,” Mel wrote. “Their last opening wedges—the foreign concessions—are fastly becoming subject to Japanese pressure.”

Even as the Japanese took over, Mel found Shanghai society distastefully out of touch. When he went to exchange money at the American Express office, the bright blue travel pamphlets inside always seemed disconcerting to him, especially when a stretch of cold nights hit Shanghai and he saw humanitarian workers piling the bodies of Chinese laborers who had frozen to death into their trucks. Shanghai, the people in it, and the way the local Chinese were treated strained Mel’s patience to the point of anger. He said as much in one form or another in most of his letters.

“I hate to see the beggars (I’ll see millions more),” he wrote. “I hate to see the rich kids in the cabarets, I hate to see the refugees, I hate to see the lousy foreigners in Packards and minks. Lots of money is being made now on the market and in business—but the Chinese peasant is taking it on the proverbial chin.”

Bombing Season

Three quarters of a century ago, today, at the height of “bombing season,” World War II correspondent Melville Jacoby took a brief break from his radio broadcasts for NBC, his writing and photography for Time and Life magazines to write to his mother and stepfather about life in wartime Chungking, or Chongqing, then the capital of China.

Three quarters of a century ago, today, Melville Jacoby took a brief break from his radio broadcasts for NBC, his writing and photography for Time and Life magazines, and his chaotic search for a panda -- yes, a panda -- to write to his mother and stepfather about life in wartime Chungking, or Chongqing, then the capital of China.

Though the two-page letter was heavy with detail, Mel apologized for not writing more.

"Please say hello to the family for me," he wrote. "I just can't possibly write now. Perhaps a little later after bombing season."

Bombing season. Think about that for a second. A time of year when enemy bombers were such a regular sight overhead that you never fully unpacked from air raid evacuations. You became used to the idea that an air raid will regularly interrupt your day, as if it's an inconvenience like the 4 p.m. Southern Pacific train that slows your commute. You reach a point when you can't help but be reminded of bombs even when there aren't enemy planes overhead, as Mel did every time he fell asleep in Chungking's Press Hostel:

"I can see the sky from my bed quite clearly, but we call it home," Mel wrote of the compound where many foreign journalists lived and worked together. It was an uncomfortable home, one that a shift in Japanese tactics made less comfortable by the day, but it was still home.

For more about Melville Jacoby, wartime Chungking, and life in the Press Hostel, check out Eve of a Hundred Midnights.

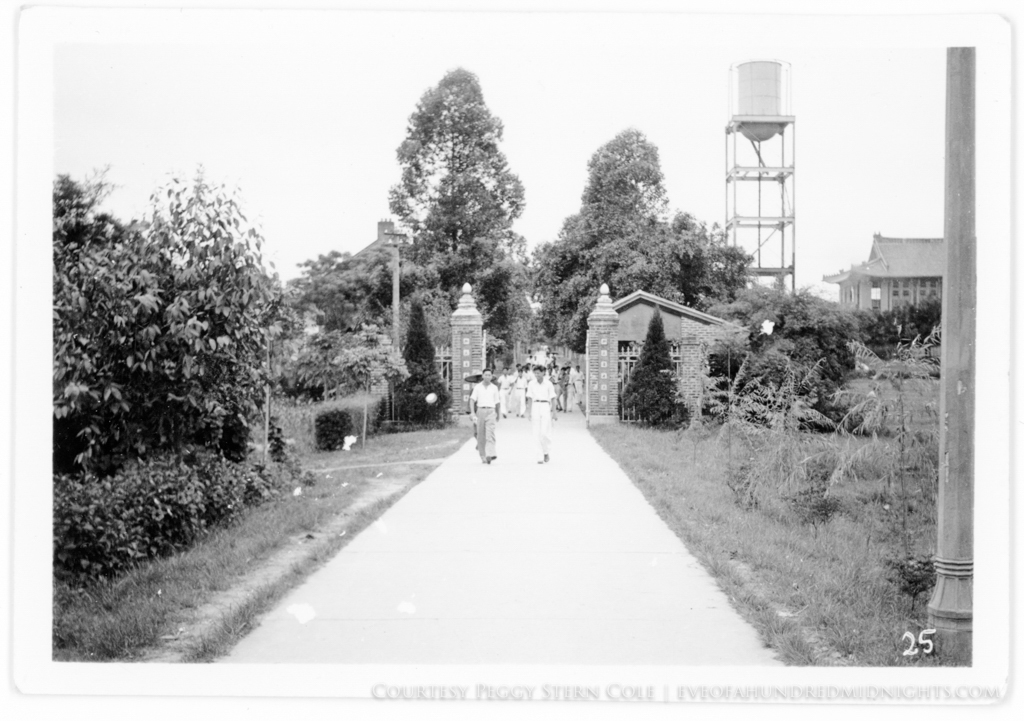

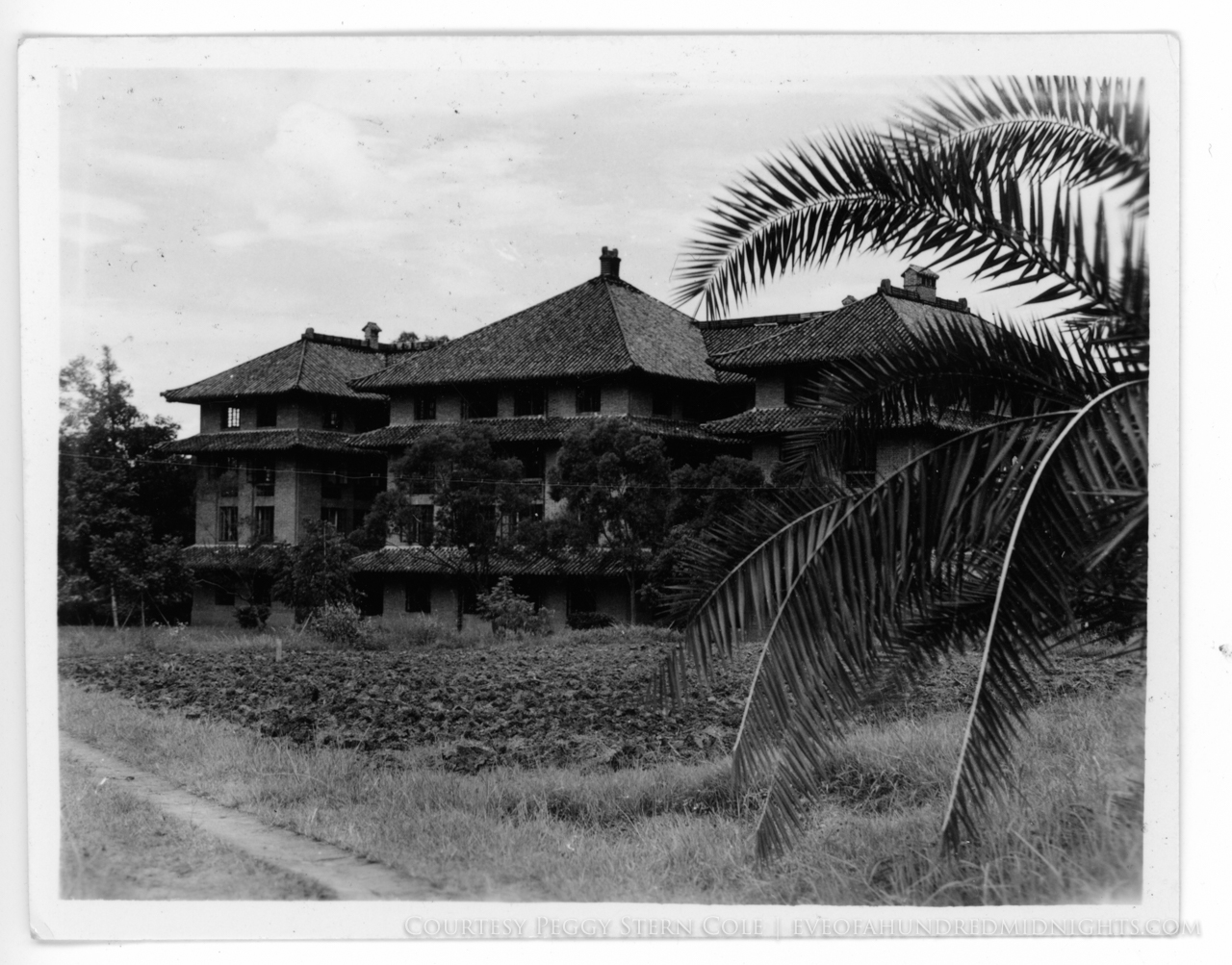

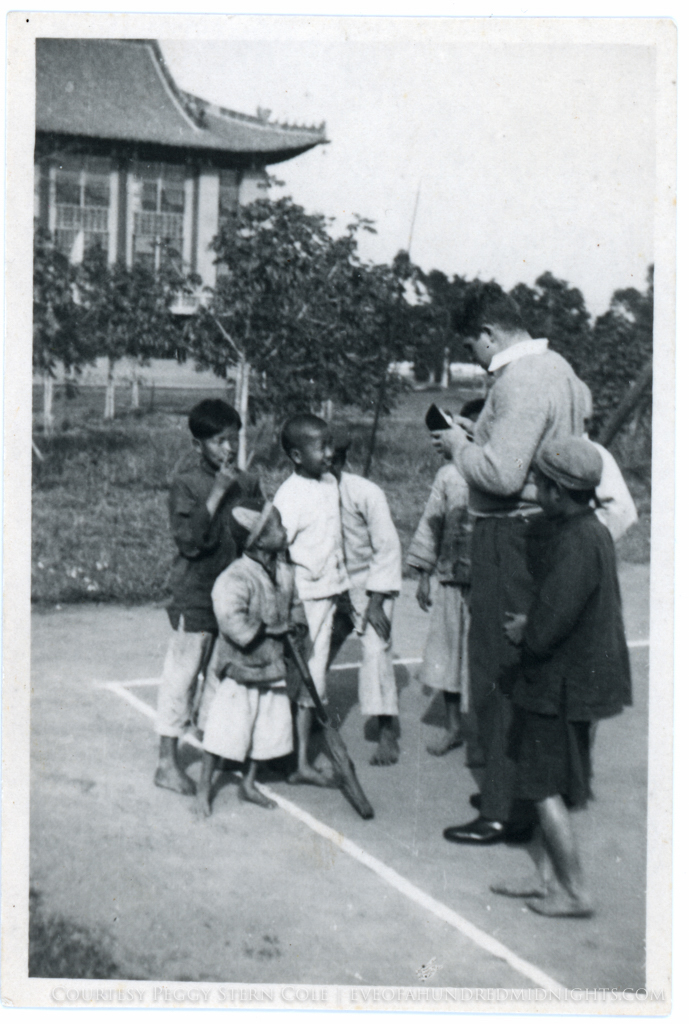

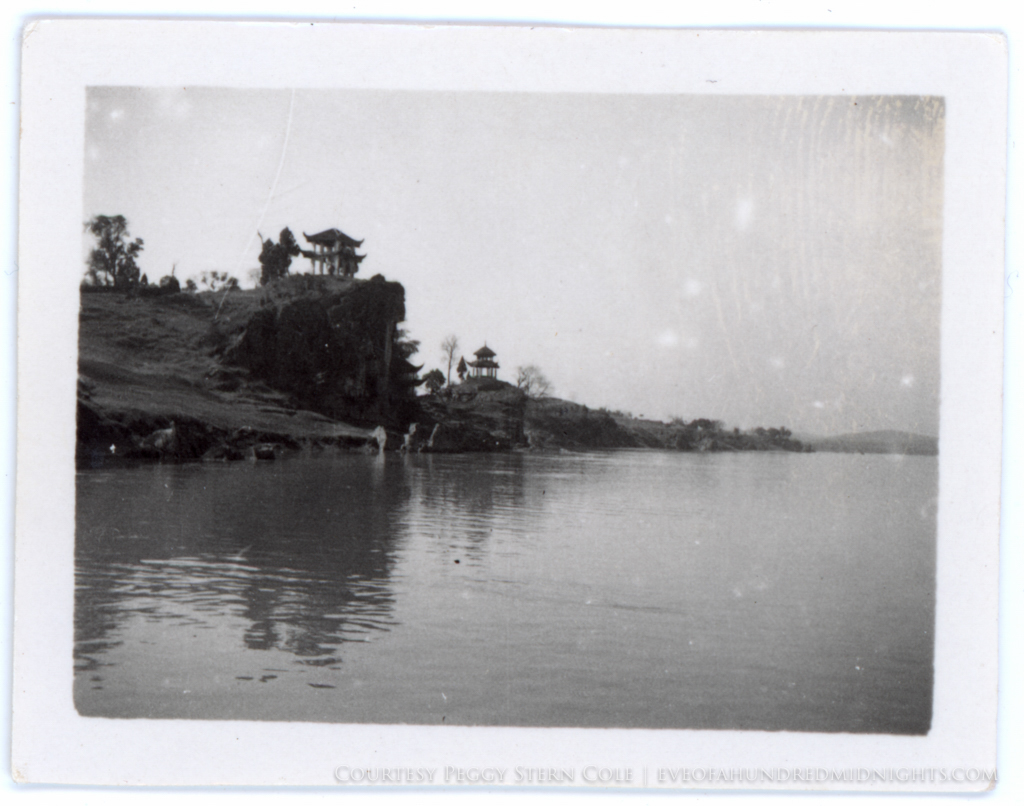

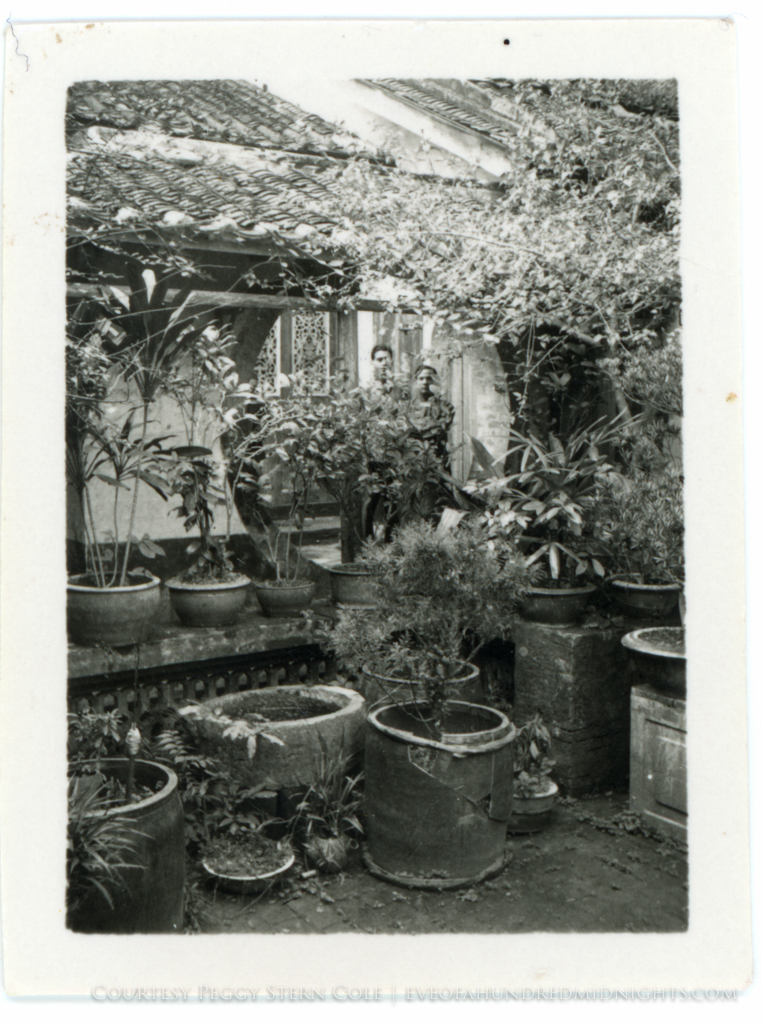

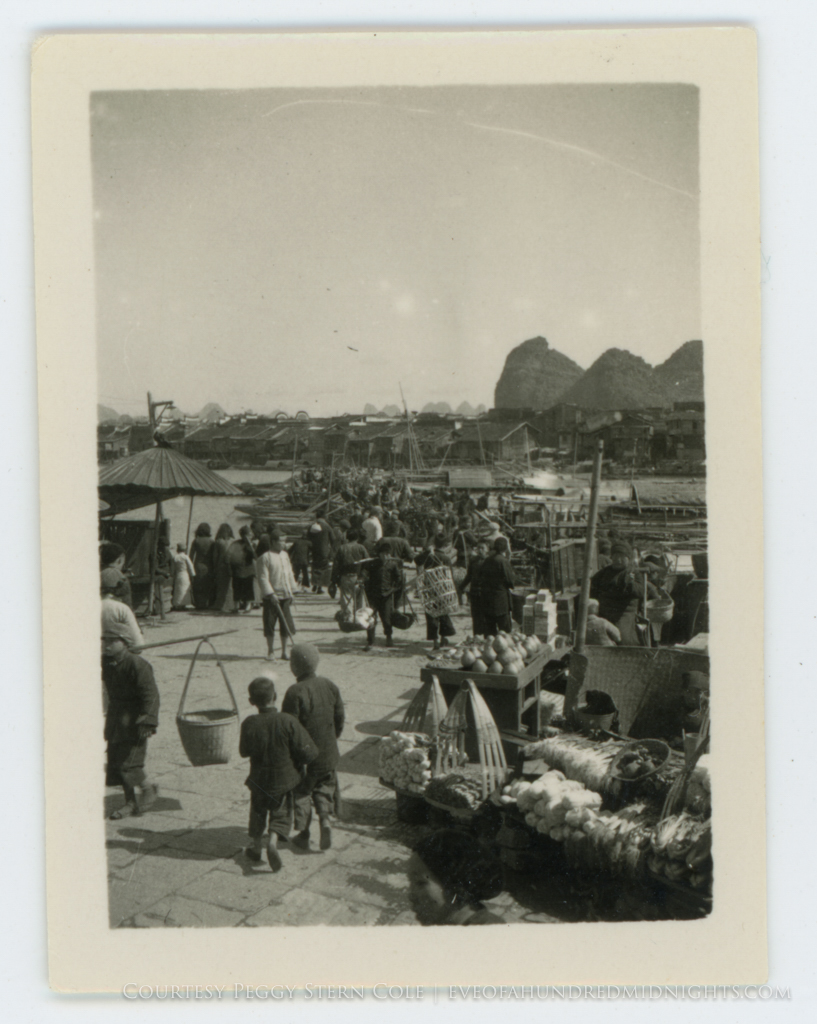

The Year that Changed Mel...And China

Melville Jacoby's interest in China can be traced back to 1936. That year and into 1937, during what would have been Mel's junior year at Stanford University, he went to China as an exchange student. There, he studied in the southern port city of Canton (that was the English transliteration of the time; it is now commonly transliterated as Guangzhou). He joined other American and Chinese students on the campus of Lingnan University (which still exists in another form in Hong Kong, while its original campus remains as part of Sun Yat-sen University in Guangzhou).

Melville Jacoby's interest in China can be traced back to 1936. That year and into 1937, during what would have been Mel's junior year at Stanford University, he went to China as an exchange student. There, he studied in the southern port city of Canton (that was the English transliteration of the time; it is now commonly transliterated as Guangzhou). He joined other American and Chinese students on the campus of Lingnan University (which still exists in another form in Hong Kong, while its original campus remains as part of Sun Yat-sen University in Guangzhou).

The year was as transformative for China as it was for Mel. That December, China's then leader, Chiang Kai-Shek (Jiang Jieshi) was kidnapped and held under house arrest near the city of Sian (Xi'an), leaving Chinese politics in a lurch. Though the crisis was resolved two weeks later with new (temporary) cooperation between Chinese communists and Chiang's Kuomintang (Guomindang) Party, by the summer of 1937 China went to war with Japan. Mel was there when the fighting began, and the conflict that became World War II would dominate the rest of his life and work.

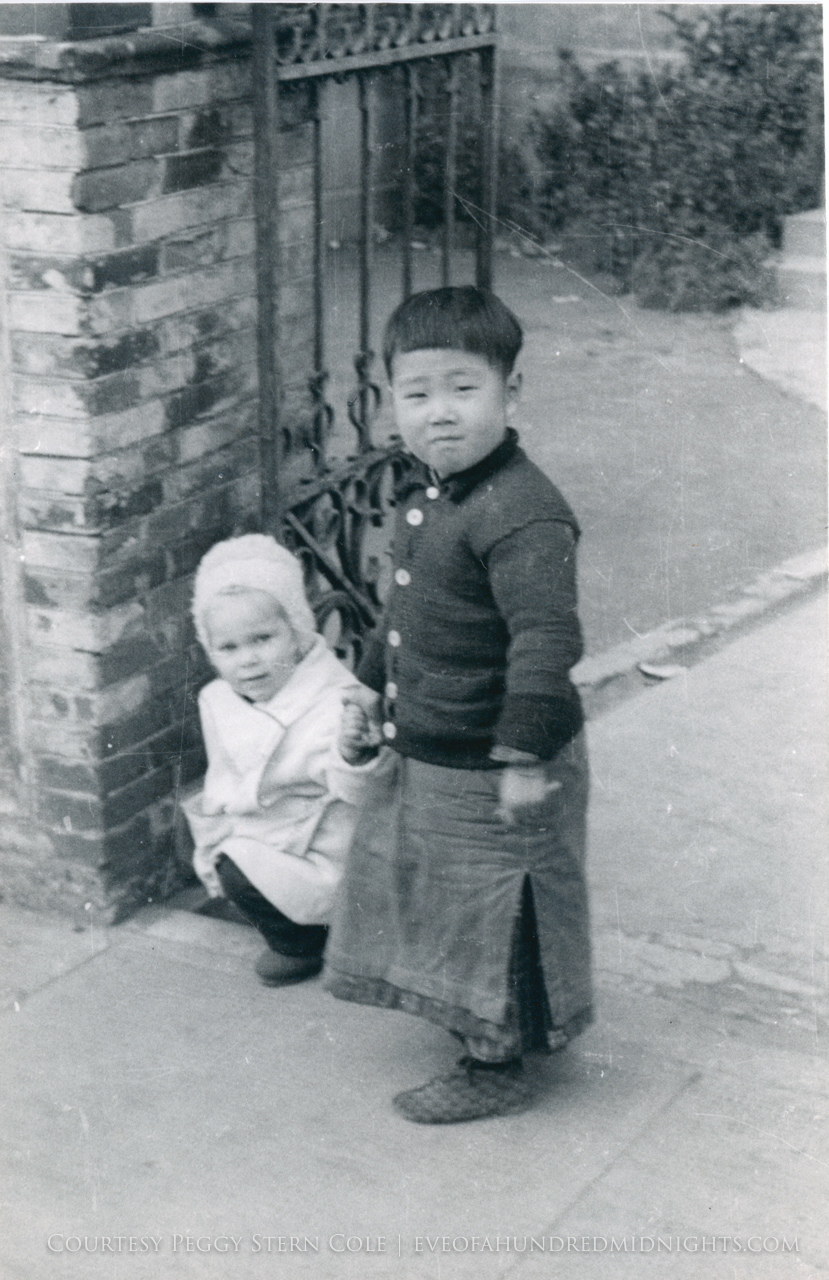

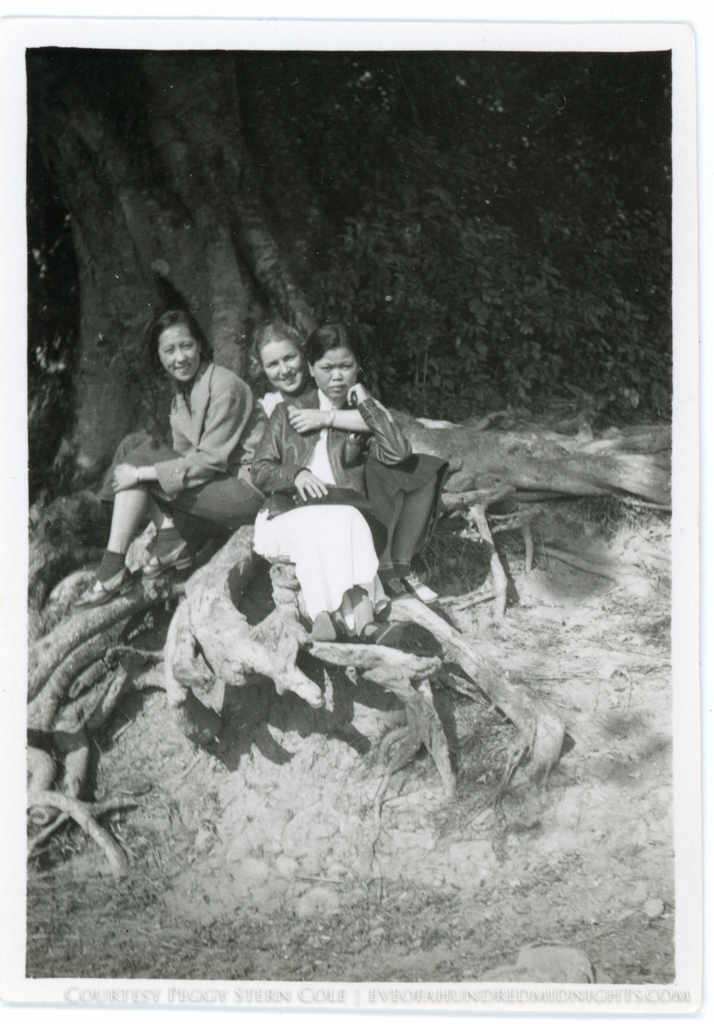

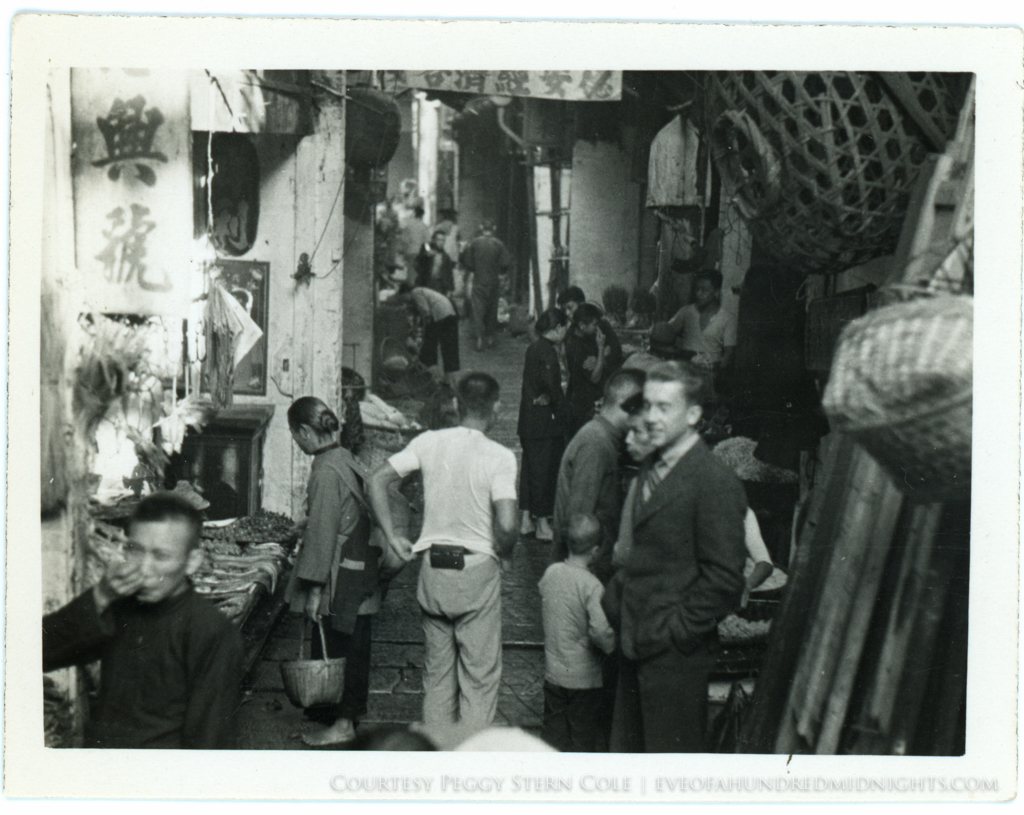

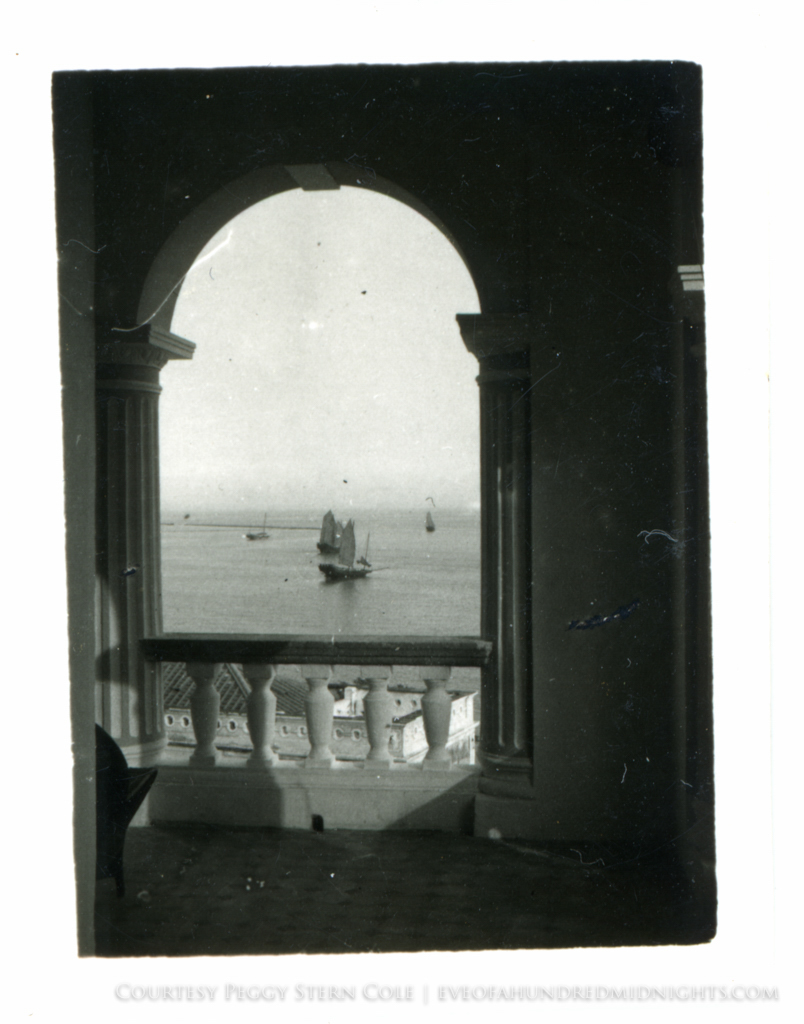

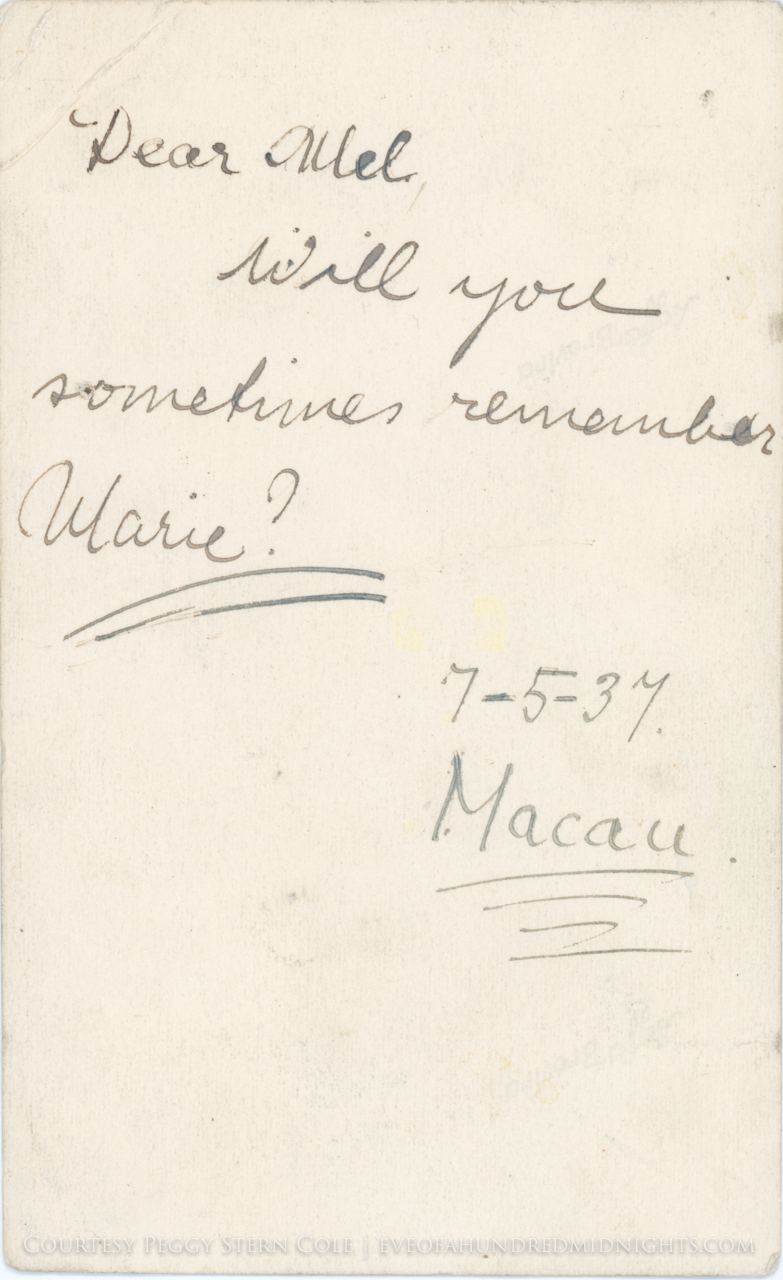

But Mel was also a fairly typical 20-year-old student when he was at Lingnan, and the following pictures depict the life of a western student at Lingnan, as well as some of what Mel saw in surrounding regions of China. To see more pictures, click on the "Images of the Past" button in the menu and choose a portion of Mel's life.

Read more about Mel's story today in Eve of a Hundred Midnights, available now!

Search Posts

Archived Posts

- March 2024 1

- October 2023 1

- October 2022 2

- December 2017 1

- April 2017 1

- February 2017 1

- January 2017 1

- November 2016 2

- August 2016 2

- July 2016 2

- December 2015 1

- November 2015 2

- September 2015 3

- April 2015 1

- March 2015 1

- February 2015 1

- January 2015 4

- August 2014 1

- May 2014 1

- April 2014 4

- March 2014 6

- December 2013 1

- November 2013 1

- August 2013 3

- May 2013 2

- April 2013 1

- December 2012 3

- November 2012 2

- October 2012 2

- September 2012 3

- August 2012 6

- July 2012 4

- June 2012 1

- May 2012 6

- April 2012 2

- March 2012 3

- January 2012 2

- September 2011 2

- August 2011 2

- July 2011 1

- May 2011 9

- April 2011 2

- March 2011 1

- January 2011 2

- November 2010 1

- October 2010 1

- August 2010 3

- July 2010 1

- June 2010 1

- May 2010 12

- April 2010 2

- March 2010 1

- January 2010 1

- December 2009 1

- November 2009 4

- October 2009 2

- September 2009 2

- August 2009 1

- July 2009 1

- June 2009 4

- May 2009 1

- March 2009 5

- February 2009 4

![Restaurant Rosenthal With Bike in Foreground [Good shot] Shanghai.jpg](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/51db1d79e4b03e2f06324d97/1473379937704-QU4YB2Z2NR49I06U7QDN/Restaurant+Rosenthal+With+Bike+in+Foreground+%5BGood+shot%5D+Shanghai.jpg)

![The Canton Landing [Front].jpg](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/51db1d79e4b03e2f06324d97/1473380873324-VJXP95LPJKSKH3YX0ME4/The+Canton+Landing+%5BFront%5D.jpg)

![Typical Canton Street Scene [Front].jpg](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/51db1d79e4b03e2f06324d97/1473380887168-QG8KGN67431O5CFBSPU1/Typical+Canton+Street+Scene+%5BFront%5D.jpg)

![Typical Canton Street Scene [back].jpg](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/51db1d79e4b03e2f06324d97/1473380886234-AWCQAHCJZGI2NXOXPESO/Typical+Canton+Street+Scene+%5Bback%5D.jpg)

![One of the Hawaiian Chinese Girls [Front]-2.jpg](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/51db1d79e4b03e2f06324d97/1469736497421-JDTW1R4G8WMPFTPGWLYA/One+of+the+Hawaiian+Chinese+Girls+%5BFront%5D-2.jpg)

![Lingnan Meal With Students Identified [Front].jpg](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/51db1d79e4b03e2f06324d97/1469736475226-XQ155UF2HIZ4DW5DZXMO/Lingnan+Meal+With+Students+Identified+%5BFront%5D.jpg)

![Head Ama Ay Ti [front].jpg](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/51db1d79e4b03e2f06324d97/1469736463411-HWUEGD604VBMRKON0J2U/Head+Ama+Ay+Ti+%5Bfront%5D.jpg)

![Chinese Dragon Up Close [Front].jpg](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/51db1d79e4b03e2f06324d97/1469736442019-XIW0UYWY93YT1ENOU2AN/Chinese+Dragon+Up+Close+%5BFront%5D.jpg)

![Barefoot Soldiers [Likely in Guangxi].jpg](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/51db1d79e4b03e2f06324d97/1469736421060-PVFIHAKH8UZ7LHDC0OG3/Barefoot+Soldiers+%5BLikely+in+Guangxi%5D.jpg)

![Monastary Square Print [Front].jpg](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/51db1d79e4b03e2f06324d97/1469736494921-7LQSGLBD2S2Y7DXOI89W/Monastary+Square+Print+%5BFront%5D.jpg)

![Street Scene in Kulangsu [Front].jpg](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/51db1d79e4b03e2f06324d97/1473380912005-VMADU257LY8ASFINK1Y3/Street+Scene+in+Kulangsu+%5BFront%5D.jpg)