Appreciation

Last night, April 24th, 2017, the Oregon Book Awards took place in Portland. Eve of a Hundred Midnights was nominated for the Frances Fuller Victor award for general nonfiction. While the book didn't win, it was such an honor to be chosen a finalist. Moreover, being asked to write some remarks in case I did win proved to be a wonderful opportunity to reflect on all of the people I appreciated for making this book possible. Here's what I would have said, because it's all still true.

Last night, April 24th, 2017, the Oregon Book Awards took place in Portland. Eve of a Hundred Midnights was nominated for the Frances Fuller Victor award for general nonfiction. While the book didn't win, it was such an honor to be chosen a finalist. Moreover, being asked to write some remarks in case I did win proved to be a wonderful opportunity to reflect on all of the people I appreciated for making this book possible. Here's what I would have said, because it's all still true:

Today marks the 75th anniversary of what could have been the last time my grandmother, her parents, and the rest of her family heard the voice of Melville Jacoby, my grandma's beloved oldest cousin and the subject of my book. That night three quarters of a century ago, everyone gathered around their radio listening to the March of Time, hoping to hear from Mel, a reporter who, with his wife, the journalist and former MGM screenwriter Annalee Whitmore Jacoby, had just survived a month-long escape from the Philippines, and six weeks of reporting from the front lines of Bataan and Corregidor.

Mel's broadcast failed and his family didn't get to hear his voice again. However, three quarters of a century later, thanks to my grandmother, Peggy, and her sister, Jackee, I've been able to give voice to his story. This award honors not just them, or Mel, but the people whose voices were only heard because Mel sacrificed so much as a foreign correspondent.

It's an honor to be nominated among this wonderful group of fellow writers, in part because many of them have produced work that amplifies the voices and subjects too often overlooked, marginalized or forgotten.

I would not have been able to tell this story were it not for others in my family as well, especially my mother, Wendy — my first and often shrewdest editor — her siblings, and my own siblings. Likewise, my partner, Andrea, has helped me survive every stage of this book's production and championed me even when I second-guess myself

Over the course of seven and a half years, more than half of which I spent on this book, Oregon has become my home. While today, too many ominous signs remind me of the dark world in which Mel and Annalee worked as reporters, the community I've found here in Oregon and what I like to call its "pot luck" culture are key reasons why I'm hopeful we'll all be able to survive whatever comes next. Many of those I've met here, whether writers or not, have contributed something that helped me make this book possible, and in turn, ensured that I have been able to get Mel's voice heard once again.

Into the Blackness Beyond

"We are remembering MacArthur’s men, how hard it was to finally leave, how lucky the three of us are."

On February 23, 1942, Seventy-five years ago as I write, Melville and Annalee Jacoby crossed the two-mile-wide channel between the fortress island of Corregidor and the besieged Bataan Peninsula for the last time. There, there would wait until sundown when a small inter-island freighter, the Princesa de Cebu, arrived in the channel, ready to sneak through the Japanese blockade surrounding the Philippines' largest island, Luzon. Their hope: escape to unoccupied portions of the Philippines and then, if they were lucky, find another ship through Japanese waters to allied territory. Here is the story of that night as told in the bestselling book, Eve of a Hundred Midnights:

“We sit by the side of a Bataan roadway waiting,” Mel wrote as he and Annalee absorbed their last moments on the peninsula amid a thick knot of banyan trees near the shore. “Our visions of past months of war are vivid, clouded only momentarily during this waiting by thick sheets of Bataan dust rolling off the road every time a car or truck races by. We wonder for a moment when we will return—and how.”

Finally, escape was in sight. At dusk, a launch would arrive to take the Jacobys to the Princesa de Cebu. That ship, they hoped, would then slip past enemy patrols at the mouth of Manila Bay and carry the reporters through the Philippines—possibly even farther across treacherous, Japanese-controlled sea-lanes and on to refuge in Australia, thousands of miles to the south.

Through a pair of binoculars borrowed from a soldier on the Bataan coast, Mel peered south toward Manila. He thought he could see the rising sun of the Japanese flag fluttering over the Manila Hotel, the same place where he’d had his last Christmas dinner, where Annalee had danced with Russell Brines and Clark Lee had urged Mel to flee the Philippines. He knew that Carl and Shelley were somewhere beneath that fluttering crimson-and-white banner. A reliable confidential source had told Mel that the Mydanses were among the thousands in captivity at Manila’s Santo Tomas University, which the Japanese had turned into an internment camp. However, it had been a month since that report.

That day Mel and Annalee felt as “impregnable as the mountain,” almost invincible “for the first time in this war.” Finally, they were leaving, Mel wrote, recalling people and moments from his six weeks on Corregidor and Bataan. Leaving everything. Leaving General Douglas MacArthur. Leaving the general’s trusted lieutenants, who had become their friends. Leaving the scores of men they’d met at the front whose stories had yet to be told. They were leaving all of them behind, “most of all the scared Pennsylvania soldier who ran the first time he heard [Japanese] fire but who braved machine gun fire the second time to carry his officer off the field.”

As the Jacobys walked along the tree trail, a Jeep carrying two officers skidded into the dirt. The noise and dust shook Annalee and Mel back into the moment. They stood up and greeted the officers. It was the first time Mel really registered the weariness on the faces of those fighting in Bataan. Despite the fatigue in their eyes, neither officer mentioned their exhaustion. Instead, they chatted casually, sharing rumors and battlefield legends until the soldiers finally drove off a few minutes later. Mel and Annalee again turned to thoughts more hopeful than the soldiers’ exhaustion. Like thoughts of ice cream sodas. Could they ever taste as good as they imagined?

Finally, the sun began to set. It was time.

The couple ran back toward the shore along the tree trails. One path led to the last American planes remaining in the Philippines, the rickety trainers, a couple of obsolete fighters, the P-40 so “full of holes.” The planes were hidden next to an airstrip that resembled a hiking trail more than a runway.

Mel and Annalee were barraged by memories at each turn. They passed anti-aircraft batteries, a motor pool, a machine shop, even a bakery (though one that had never had bread to bake) and a makeshift abattoir where first caribou, then mules, then even monkeys were slaughtered for the soldiers’ meals.

Across the narrow channel from Bataan, Clark Lee had finished wrapping up his own affairs on Corregidor, and now he was waiting for the Jacobys at the same dock on the island’s north side where the trio had come ashore on New Year’s Day. He did bring a typewriter, as well as a razor, a toothbrush, and a change of clothes.

The Princesa approached at dusk, slowly steaming westward. They boarded and were greeted by four British and two American civilians who had received field commissions after fleeing from Manila to Bataan. They had boarded the Princesa from a separate launch earlier. Among them was Lew Carson, a Shanghai-based executive for Reliance Motors hired by the army to help manage its motor pool, and Charles Van Landing-ham, a former banker who escaped to Bataan on a tiny sailboat on New Year’s Eve. Also a contributor to the Saturday Evening Post, Van Landingham was struck by how deceptively peaceful the green jungles of Bataan looked as he left.

“It was hard to realize that under that leafy canopy thousands of hollow-eyed, half-sick men stood by their guns, fighting on grimly in the hope that help would come before it was too late,” Van Landingham wrote.

Its lights dark, the Princesa slowly made its way into mine-laden Manila Bay. Huge searchlights on Fortuna Island scanned the sky above the island as its “ack-ack” guns—anti-aircraft artillery—fired at Japanese bombers. The darkness gave way momentarily to the glow of the guns’ tracers, which lit the passengers’ faces. Then night returned across the ship’s deck.

From Corregidor, a searchlight swept the coast in front of the Princesa. A small, fast torpedo boat appeared and led the ship through the mines, barely visible but for the path carved by its wake. The craft was skillfully piloted by Lieutenant John D. Bulkeley, who provided a few minutes of covering fire while guiding the Princesa toward the mouth of Manila Bay. Then, in a final farewell gesture, Bulkeley flashed the torpedo boat’s starboard light and roared back to Bataan, leaving nothing but darkness in his wake.

Night on the Pacific washed across the Princesa. Only the distant flash of Japanese artillery punctuated the dark. The ship’s two masts bobbed beneath what Mel’s eyes found to be a “too bright moon.” This was the same moon the soldiers on Bataan prayed would descend quickly, lest even a quick glint of its light across a shining service rifle’s barrel draw a sniper’s bullet. Now the moon cursed the Princesa. The nearby shore was dark, but everyone aboard the Princesa knew it crawled with enemy forces. They silently watched the passing islands. Each lurch of the ship tied the passengers’ stomachs in a “tight feeling.”

A crew member snapped a chicken’s neck. The reporters jumped at the bird’s sudden, loud squawk.

It was just dinner, but everyone crossed their fingers.

“Sure, we’ll make it,” someone said. “Easy.”

All three reporters rapped their fists on the wooden deck.

Nobody slept. Everyone kept watch, fearful of missing even the briefest moment of movement. Finally out of Manila Harbor, the ship maneuvered toward the southeast and crept through the darkness along Batangas, on the Luzon coast south of Manila.

Thousands of miles, countless inlets and islands, circling recon planes, even submarines and destroyers dispatched by the Philippines’ new conquerors lay between the reporters and safety in Australia. They spoke little. Instead, they reflected privately on the soldiers they had met on Corregidor and Bataan, the onslaught both places had endured, and their own good fortune so far.

“We talk very little sitting on deck now. We are remembering MacArthur’s men, how hard it was to finally leave, how lucky the three of us are. We’d gotten through the [Japanese] before,” Mel wrote. “Everything we’ve known the past two months is swallowed in blackness beyond.”

75 Years Ago, When War Seemed a Million Miles Away

75 years ago, today, Pearl Harbor was on the horizon, but for one couple in Manila, war briefly felt a million miles away.

Seventy-five years ago, today, with the United States and Japan on the brink of war, Time Magazine correspondent Melville Jacoby married the former Annalee Whitmore, a former MGM scriptwriter who had been managing publicity for an aid organization known as United China Relief. The following excerpt from Eve of a Hundred Midnights (William Morrow, 2016) describes the moment Annalee arrived in Manila from Chungking, the wartime capital of China, and Mel whisked her off to their wedding. Pick up the book from your favorite retailer to find out how Mel and Annalee's paths crossed, and what happened when war broke out just two weeks after their wedding.

From the edge of Pan-Am’s facilities along the southern arc of Manila Bay near the Cavite shipyard, Mel watched a Boeing 314 cross the sky. It was Monday, November 24, 1941, just three days before Thanksgiving.

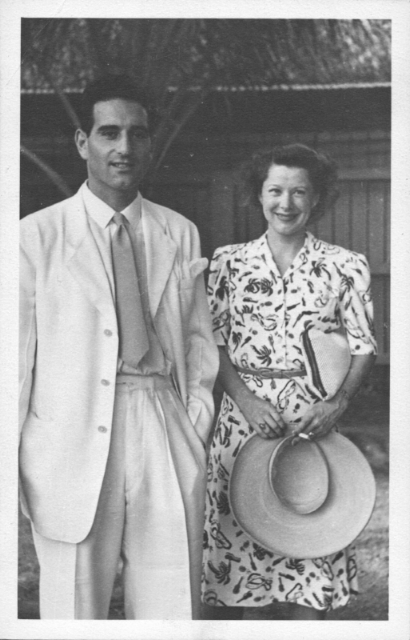

Annalee was on the plane. As it landed she spotted Mel at the water’s edge, clad in a gleaming white suit, white shirt, and yellow tie.

“I could see him when the plane landed in the water, and it seemed like hours until they pulled it up onto the beach,” Annalee later wrote to Mel’s parents.

Finally, the Clipper’s pilot cut the aircraft’s engines. The plane coasted the last few feet to the dock, where its passengers disembarked. Annalee barely had time to say anything to her fiancé. After they embraced, Mel ushered her to a waiting car, which drove the ten miles from Cavite to Manila, turned right off Dewey Boulevard onto Padre Faura, then stopped at the Union Church chapel a couple of blocks away. Mel strode confidently up to the church, while Annalee, wearing a white nylon dress printed with palm trees, ukuleles, pineapples, and leis in green, yellow, and red, linked her arm in his, smiling widely, a broad-brimmed yellow hat tucked under her other arm. For a couple who never expected romance, it was as dreamlike as any fairy tale.

“It was just like I’d always hoped it would be,” Annalee wrote.

Carl and Shelley Mydans were there, as well as Allan Michie (a Time reporter about to transfer to England, Michie was also the author of Their Finest Hour) and the Reverend Walter Brooks Foley. As soon as the couple arrived, the small pro- cession gathered in an intimate reception room off the chapel decorated with white flowers and green drapes. Carl served as Mel’s best man; Shelley was Annalee’s matron of honor.

Reverend Foley performed the modest ceremony. Mel had always dreaded large, formal weddings. He had looked for a justice of the peace to officiate, but most of the ones he found spoke little English and held ceremonies in nipa huts—small stilt houses with bamboo walls and thatched roofs made from local leaves.

“The morning I came he found Reverend Foley, who was a short blond near-sighted angel, full of extravagant plans for choir chorales and processionals and borrowed bride giver-awayers,” Annalee wrote.

Annalee may not have wanted a big to-do or an ostentatious ring, but she clearly couldn’t restrain her delight at the occasion itself. Her smile did not subside throughout the ceremony. Her hands gently clasped Mel’s as they exchanged vows, and she looked intently at her husband, her eyes grinning and warm. For his part, Mel couldn’t mask the pride on his face, nor his joy.

Within an hour of Annalee’s landing, she and Mel were married. After their wedding, they wrote letters to their families. In one, Annalee insisted to Mel’s parents that she didn’t go to China to marry Mel, but she “couldn’t think of a better reason” to have gone.

The celebration continued at the Bay View Hotel, just a few blocks away. Gathered in the lobby were many of the couple’s friends who had also transferred to Manila from Chungking, as well as others Mel had met since arriving. Those who couldn’t be there sent their congratulations. Everyone, from Annalee’s colleagues at MGM to Henry and Clare Boothe Luce, to all the Press Hostel residents, to the entire staff of XGOY (which also aired a brief item about the marriage), sent their good wishes.

“General MacArthur about knocked me over the other p.m. congratulating me,” Mel wrote. “Admiral [Thomas] Hart’s staff nearly shook my hand off.”

There was a portable phonograph setting the tune with jazz standards and popular big band recordings. In between songs, the newlyweds ducked into a corner of the lobby where they took turns placing long-distance phone calls to their parents in Los Angeles and Maryland. And then they danced into the night. War was on the horizon and could arrive any day, but that evening it could have been a million miles away.

Shanghai Takes it On the Chin

“I hate to see the rich kids in the cabarets, I hate to see the refugees, I hate to see the lousy foreigners in Packards and minks. Lots of money is being made now on the market and in business—but the Chinese peasant is taking it on the proverbial chin.”

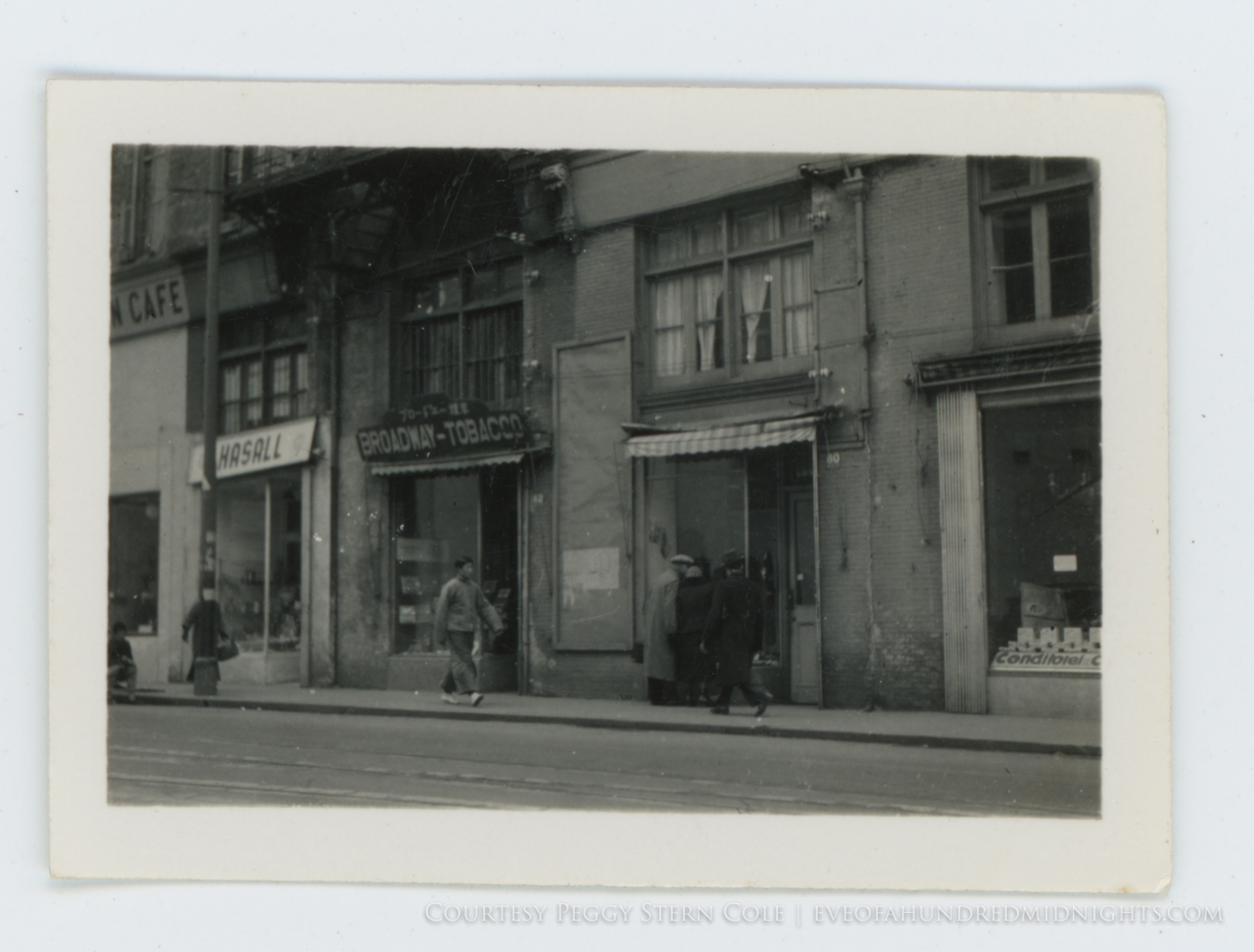

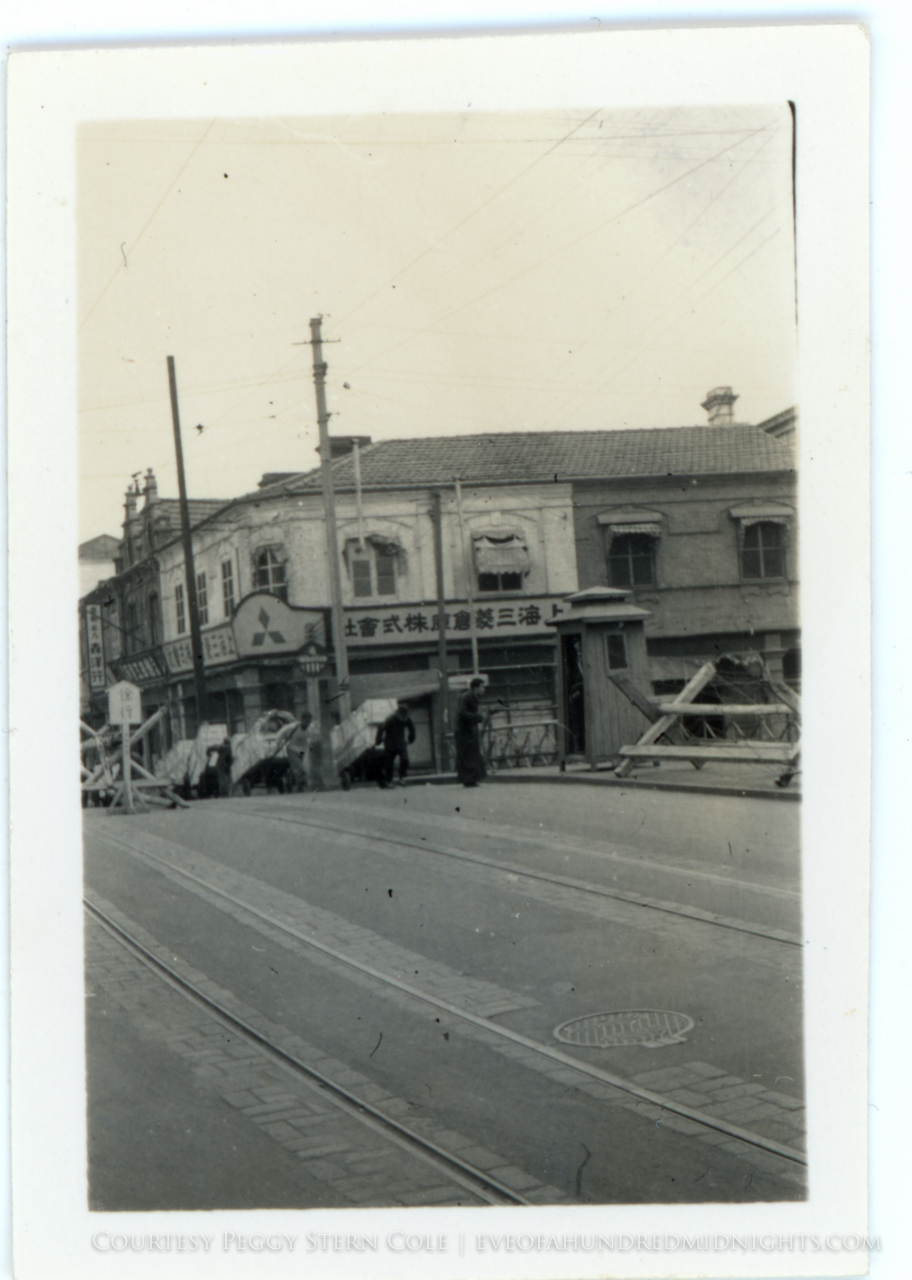

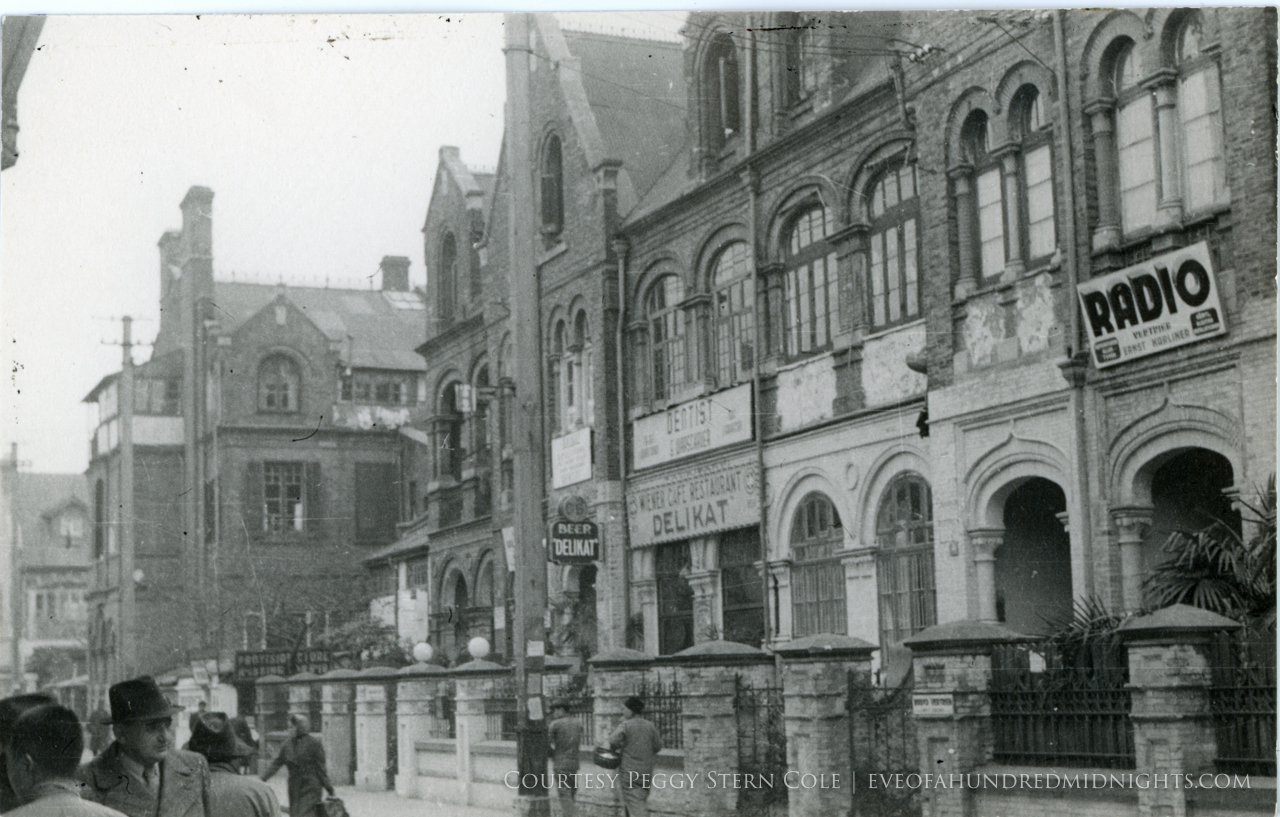

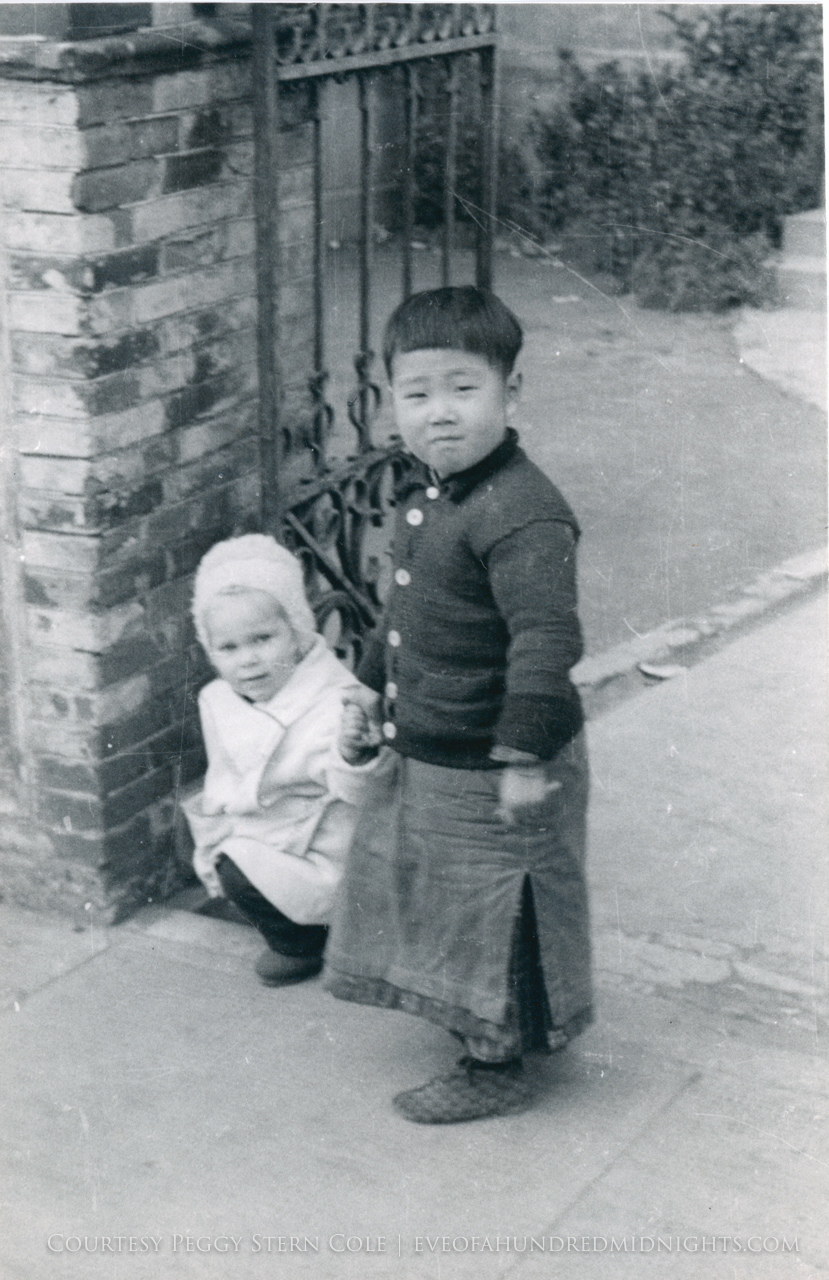

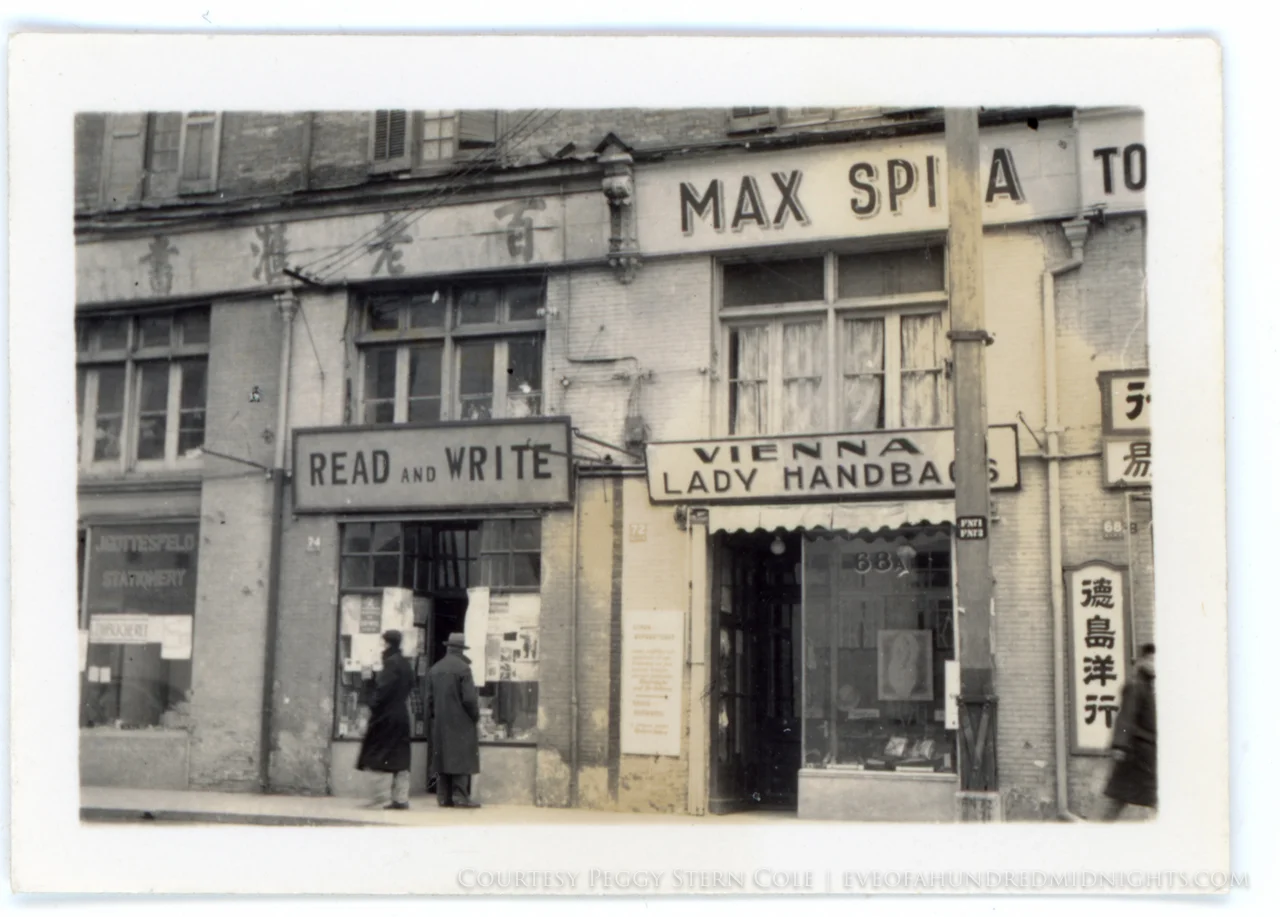

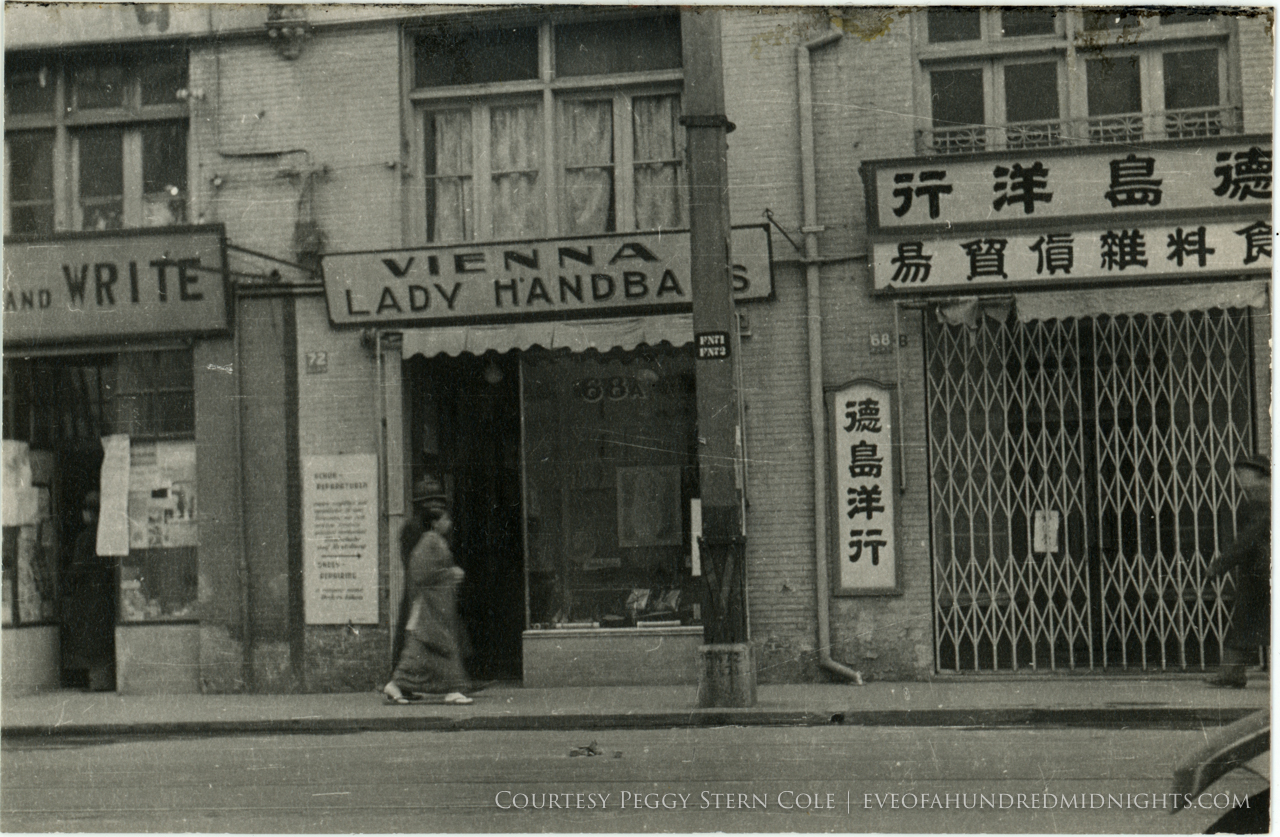

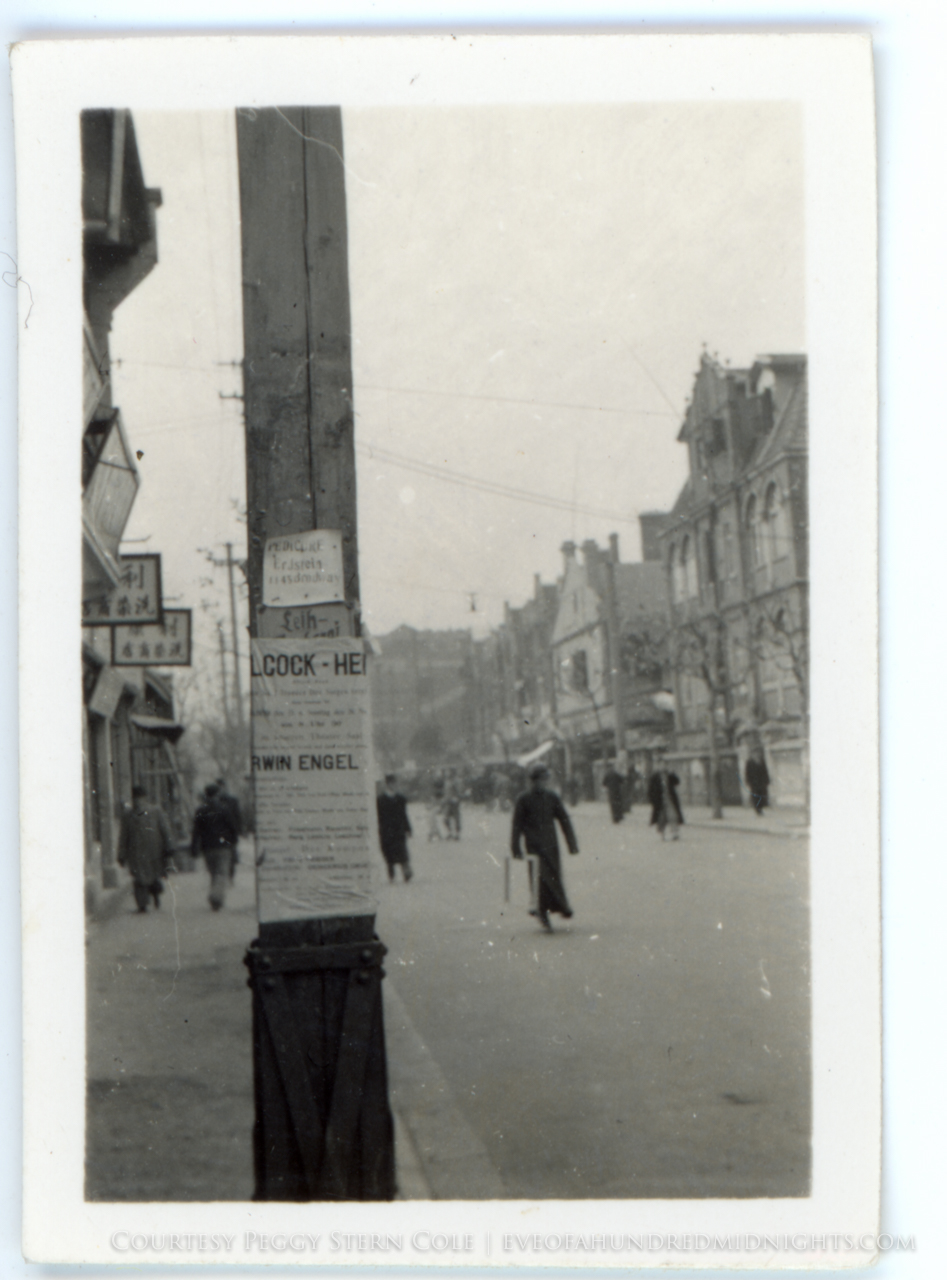

In November, 1939, Melville Jacoby arrived in Shanghai, China. Having just earned his master's degree in journalism from Stanford, Mel returned to China two years after studying there as an exchange student. Mel arrived in Shanghai with no work, but a raft of letters of recommendation from newsmen and scholars who had been impressed by a presentation Mel made of his research into California newspapers' coverage of China and Japan in the run-up to a war that had been raging since the summer of 1937, just as Mel completed his exchange year. As Mel hunted for work in Shanghai, he discovered a city packed with thousands of Jewish refugees who'd been turned away by every other port on Earth. It was a city occupied by Japan, though still nominally internationally-controlled, as it had been for decades. Here are some selections of how the city looked to Mel:

Here's how I described Mel's impression of Shanghai in Eve of a Hundred Midnights:

“But if you aren’t British or French or American or if your country hasn’t got enough gunboats it isn’t so international,” Mel wrote, referring to the many foreigners who came to Shanghai butwere not nationals of countries that enjoyed extraterritorial powers. Paradoxically, among the most disenfranchised populations in Shanghai were Chinese nationals. And though Shanghai maintained much of its international identity when Mel arrived in 1939, in the two years since the Battle of Shanghai, Japan had consolidated power there and grown increasingly belligerent toward both the Chinese and Westerners.

“The Western world is being squeezed out of China,” Mel wrote. “Their last opening wedges—the foreign concessions—are fastly becoming subject to Japanese pressure.”

Even as the Japanese took over, Mel found Shanghai society distastefully out of touch. When he went to exchange money at the American Express office, the bright blue travel pamphlets inside always seemed disconcerting to him, especially when a stretch of cold nights hit Shanghai and he saw humanitarian workers piling the bodies of Chinese laborers who had frozen to death into their trucks. Shanghai, the people in it, and the way the local Chinese were treated strained Mel’s patience to the point of anger. He said as much in one form or another in most of his letters.

“I hate to see the beggars (I’ll see millions more),” he wrote. “I hate to see the rich kids in the cabarets, I hate to see the refugees, I hate to see the lousy foreigners in Packards and minks. Lots of money is being made now on the market and in business—but the Chinese peasant is taking it on the proverbial chin.”

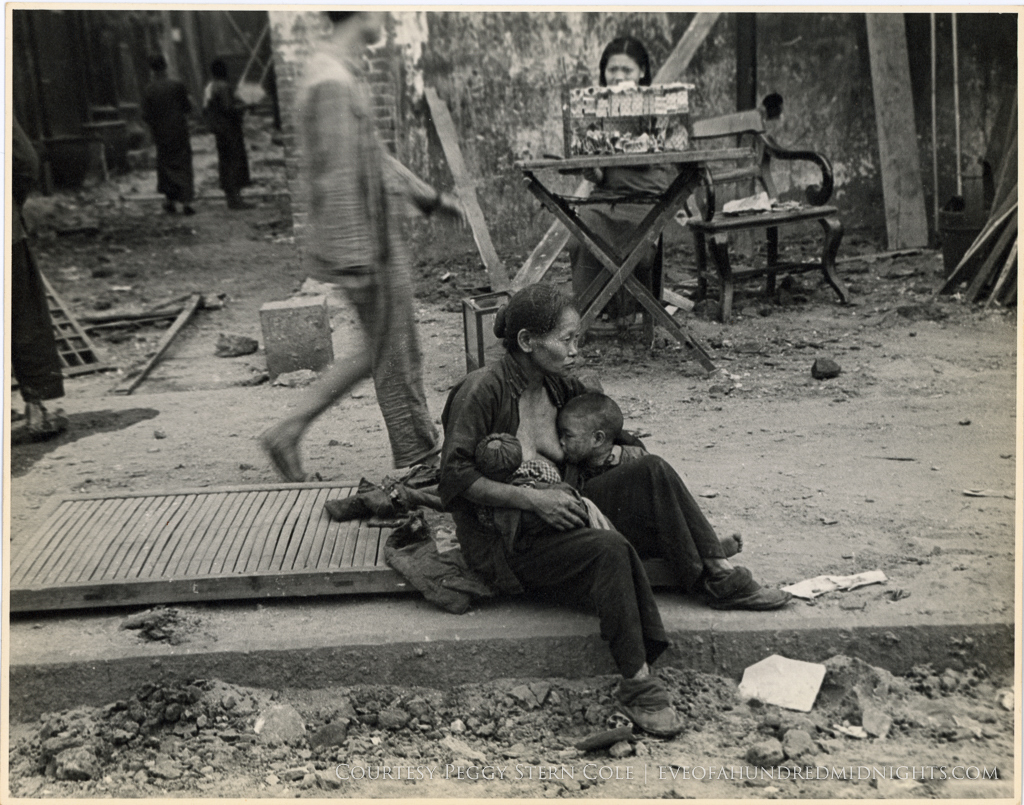

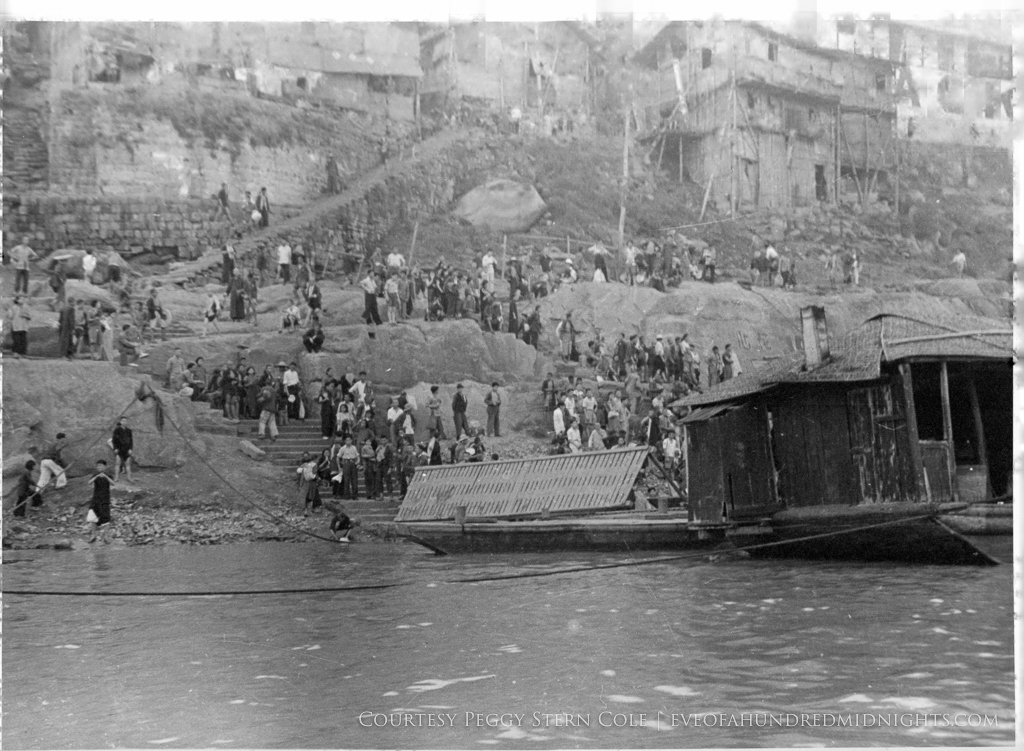

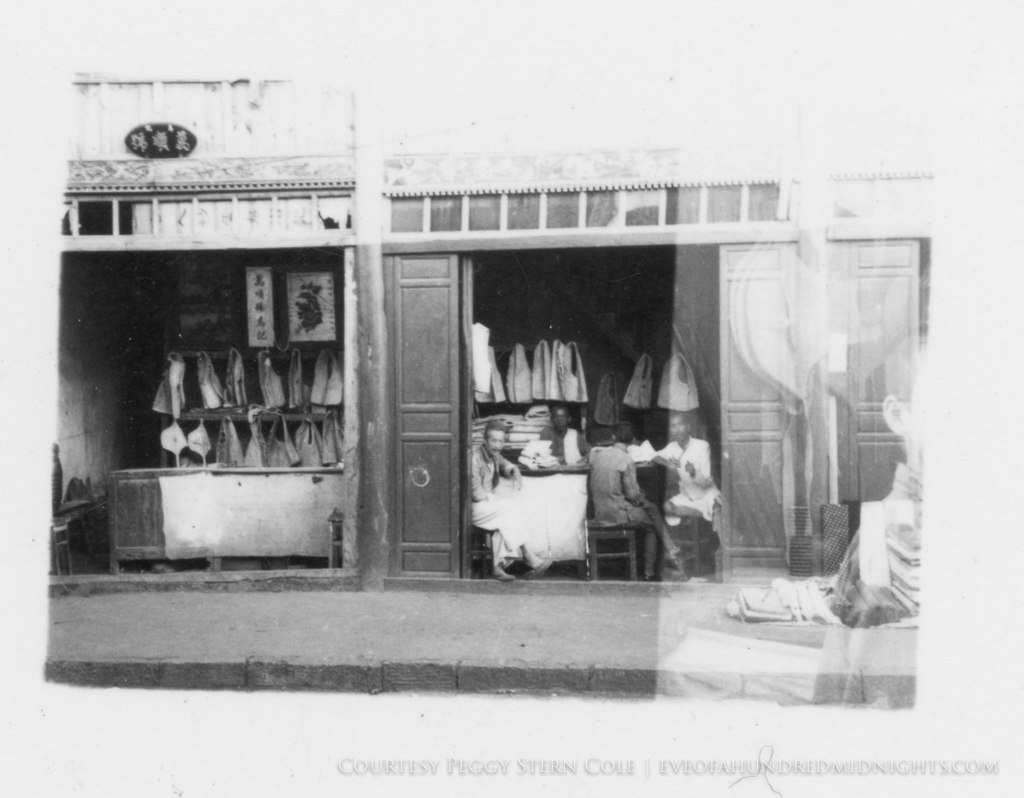

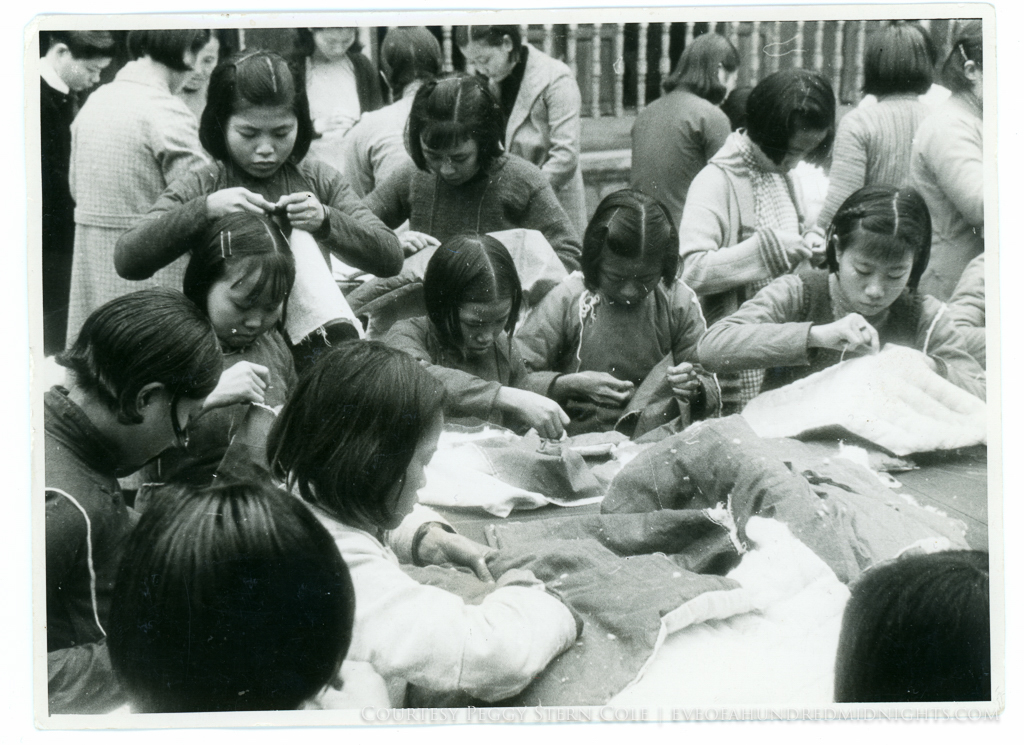

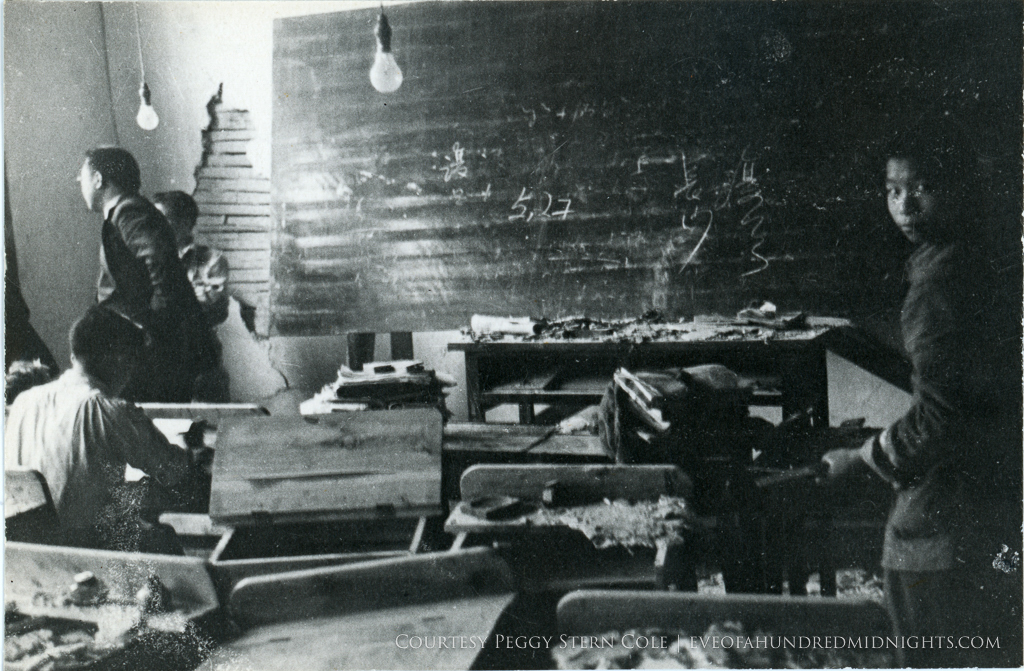

Before and After. Wartime Chongqing as Captured by Melville Jacoby's Lens.

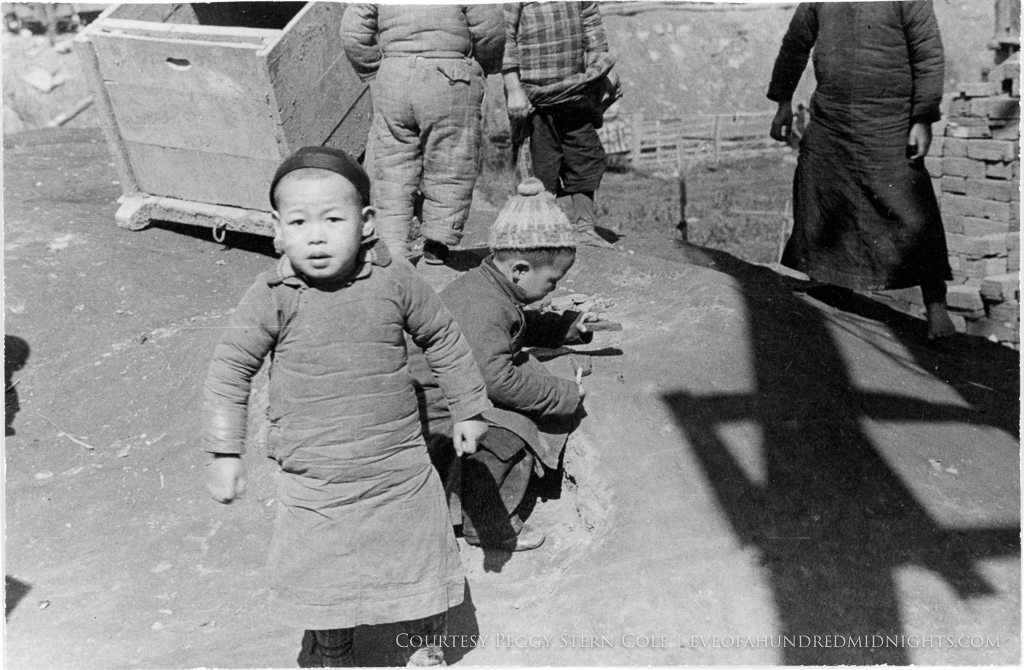

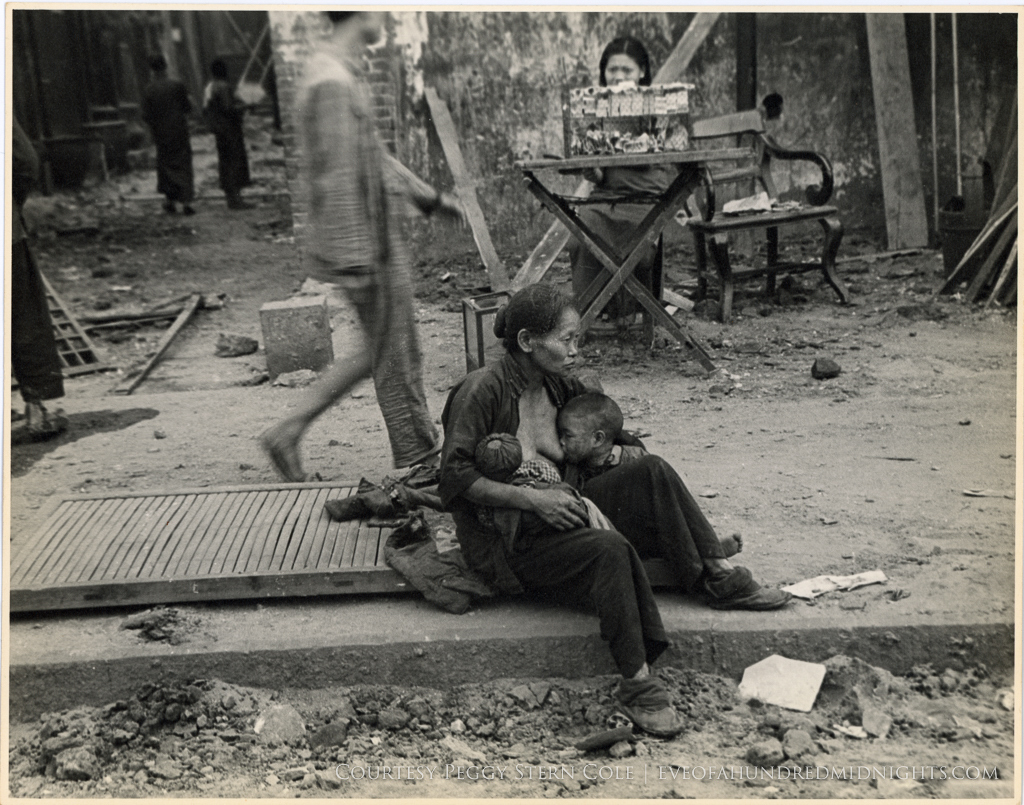

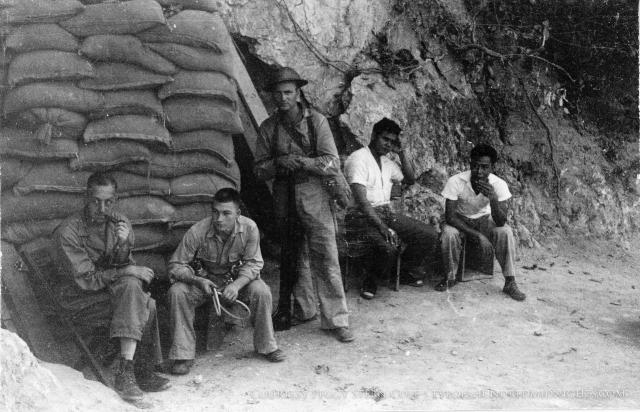

After spending four years with the research, writing and re-writing that shaped Eve of a Hundred Midnights, I feel sometimes as if I've lived in Melville Jacoby's shoes. At least, I feel as if I've seen the world through his eyes. As you can see in the following photos, Chongqing was a place of extensive striving and, after years and years of bombing — during his stints there in 1940 and 1941 Mel experienced 168 air raids — deeply scarred yet incredibly resilient.

Perhaps no place was more important to Melville Jacoby than the city of Chongqing, China (then known to westerners as Chungking). After Japan conquered China's coast and major cities such as Nanjing, Beijing, Shanghai and Wuhan, the Chinese government was forced to flee up the Yangtze river to Chongqing, where it transformed what had been something of a backwater into China's wartime capital. As I wrote in Eve of a Hundred Midnights, which was published last month, Chongqing was "simultaneously brand-new and decrepit. Fast becoming the 'most bombed' city in the world, it was also the epicenter of the country for any serious journalist." It was squalid, dangerous and extremely uncomfortable, yet, somehow, irresistible, as Mel attested:

“Few foreigners desert Chungking without wanting to return," Mel wrote. “The set formula is to tell friends in Hong Kong what a hell-hole they are missing, and then to rush right back on the next plane loaded with only thirty pounds of clothes and bare essentials.”

As you can see in the following photos, Chongqing was a place of extensive striving and, after years and years of bombing — during his stints there in 1940 and 1941 Mel experienced 168 air raids — deeply scarred yet incredibly resilient. I recently browsed Mel's photos again to share at my book readings (please get in touch if you'd like to host me in your community) that he saw these characteristics in Chongqing, and I've chosen the following photos to illustrate some of the contrasts of life in the city that Mel documented:

Click Thumbnails For Larger Images

After spending four years with the research, writing and re-writing that shaped this book, I feel sometimes as if I've lived in Melville Jacoby's shoes. At least, I feel as if I've seen the world through his eyes. His letters describe what he witnessed and experienced in China and the Philippines in such depth that as I read them, I feel my legs straining up and down Chongqing's steep hills, that I hear the thud of bombs raining upon an air raid shelter, and that my heart beats in anticipation as my fiancée lands in the Manila Bay barely a week before Pearl Harbor.

Beyond these letters, though, Mel took hundreds, if not thousands, of photographs, most of which have ended up in my hands. Unfortunately, I was only able to include a handful in my book. While I chose compelling photos, they were mostly limited to photos that portrayed Mel, Annalee and the people they knew. However, I knew readers who enjoy the book would also want to see more of the world and the era Mel did.

If you like these photos, please keep on eye on this web site and let me know what you think. I'm going to continue to share glimpses of what Mel saw here. Unless otherwise noted, the photos you will see in this series were all shot by Melville Jacoby and provided courtesy of Peggy Stern Cole, Mel's cousin and my grandmother.

Meanwhile, if you haven't already, please head to one of the booksellers listed here or your favorite bookstore to pick up Eve of a Hundred Midnights. If you like it, would you rate it on Goodreads, Amazon, Powell's, or wherever you purchased it? Customer reviews will make the difference in ensuring the book is seen by as many people as possible.

Come for the Book Cover and Release Date, Stay for the Food Poisoning

So, I could tell you a story about food poisoning and crazy rides across the Philippines, but I suspect you want to know what the cover of my book looks like, or what its final title and release date will be, or how you can pre-order it, or read about some fascinating characters from Portland who played both heroic and sinister roles in World War II.

So, I could tell you a story about food poisoning and crazy rides across the Philippines, but I suspect you want to know what the cover of my book looks like, or what its final title and release date will be, or how you can pre-order it, or read about some fascinating characters from Portland who played both heroic and sinister roles in World War II. So let's get to it!

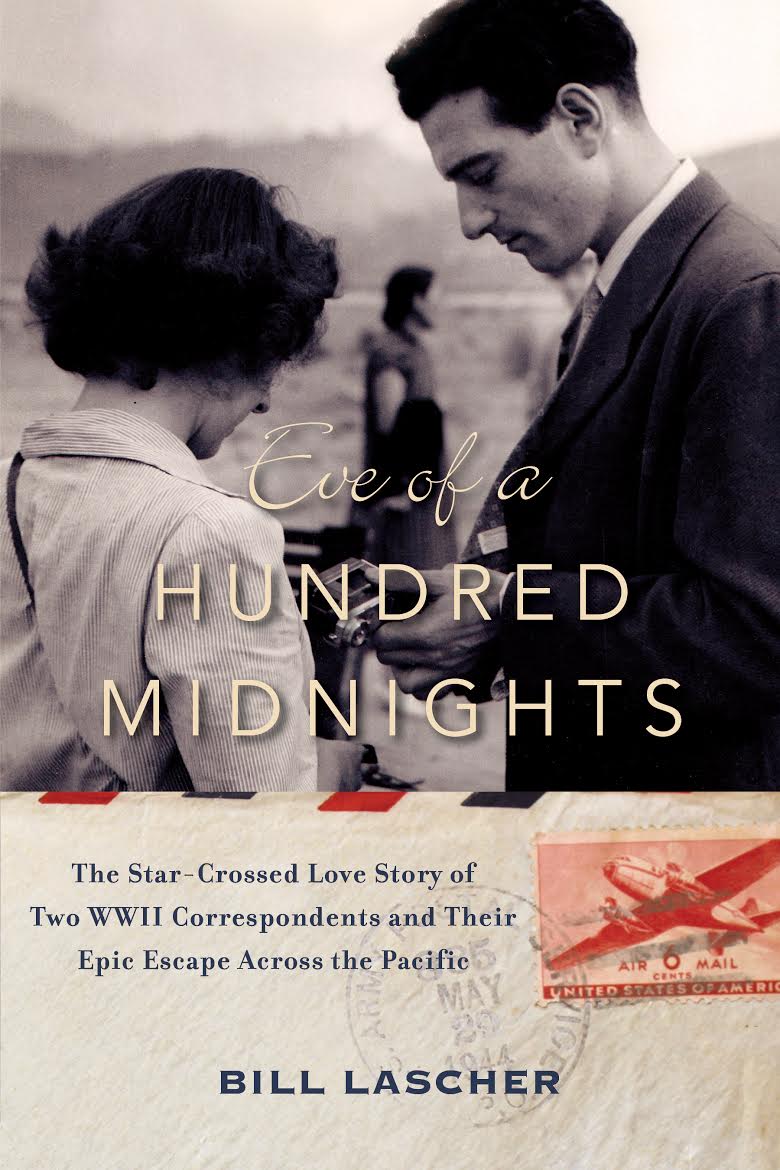

Coming June 21, 2016 from William Morrow & Co:

It was QUITE a long road to get here, but I'm thrilled to say that outside of one last proofread for style and clarity, the manuscript of my book, Eve of a Hundred Midnights, is complete. You can expect to pick it up from your favorite bookseller on June 21, 2016. I'll send out proper pre-order links once a few more booksellers' websites have bene updated, but the intrepid among you may find some on my publisher's web site.

Meanwhile, while you're waiting to read the book, take a glance at this month's edition of Portland Monthly, which explored the heroes, villains and rogues from Portland's history. I looked at two of these characters. One was Japan's foreign minister, Yōsuke Matsuoka, who yanked his country out of the League of Nations and into the arms of the Axis with Germany and Italy, and was also raised by a Portland family and a graduate of the University of Oregon School of Law. The other was Hazel Ying Lee, a heroic pilot born in Portland and the first American woman of Chinese descent to fly for the U.S. military. Lee was one of the Women Airforce Service Pilots, or WASPs, though she died just before finishing her service with the program.

Both stories were fascinating subjects that I only learned about in working on this book; I've discovered so many in this long process and hope to share more as time and resources allow.

Lapu-Lapu's Revenge

But, hey, you don't care about covers and book titles and magazine articles, right? I bet what you really want to read about is intestinal infortitude. Well, I give readers what they want, so read on!

As I was sprawled on my bathroom floor early this morning after an entirely unwelcome repeat encounter with last night's dinner, it occurred to me that last time I had food poisoning I was in Shanghai. High above the South China Sea, my stomach felt as tumultuous as relations between the country I was leaving, the Philippines, and the one to which I was returning, China.

This was a rapid turnaround from a few hours earlier, when I'd bought myself lechon to celebrate finding a key location in my book -- an abandoned beach club that was once used as a hideout by Mel, Annalee and their friends as they escaped the Philippines. It was on the island of Cebu, a skinny sliver a few hundred miles southeast of Manila, in a town just outside Cebu City, the island's capital. Aside from its role in my story, Cebu is known for lechon, and I was eager to try it. But because roasting a pig to make lechon, it's only available for a brief window every evening. Given how compressed my time on Cebu was, I had to make book research my priority.

It had been all I could do not to just give it up, get some lechon, skip the research and park myself on some sterile resort beach on the nearby island of Mactan. The night before I reached Cebu, I'd arrived by ferry to the port of Caticlan on the northwest tip of the island of Panay. A gazillion tour operators convinced I was confused, didn't want to go south, but instead wished to visit nearby resort-heavy Boracay descended upon me. I shook them off, insisted I was headed south, and squeezed myself into a packed van bound immediately -- I was assured -- for Iloilo, on the other side of the island.

Two hours after I was told we would leave, I began a frightening ride wedged on a front bench, seatbelt-less, between the driver and another passenger, with my backpack at my feet. We finally left just as it began raining, a condition that paired swimmingly with my driver's speed down the winding, two-lane highway that hugged the edge of Panay. Texting the entire way and apparently quite frustrated by the person on the other end of the line, he weaved around construction sites, slowing only to cross himself whenever we passed a churchyard. All the while he crooned along with to the 80s power-rock ballads burned on CDs that he flipped in and out of the stereo. My only sanity came from joining the driver for renditions of familiar Journey and Bon Jovi tunes I'd absorbed as a child in 1980s America; when you're far from halfway anywhere and it's clear the man behind the wheel is driving on a prayer, belting out "Wh-oa, we're half way there" takes on new significance. When we finally stopped three hours later so my driver could take a pit stop (and call the friend he'd been texting), I decided not to prolong the ordeal on another ride across Negros, then Cebu, and used the sliver of cell phone reception I had to blow my budget and spend $40 on the next plane ticket I could get from Iloilo to Cebu (yes, by that point, forty unexpected dollars were a big budget excess). Five hours after leaving caticlan, I found the one decrepit hotel in Iloilo still accepting new guests at that late hour, slept in my clothes for two more, took a cold shower, then left for the airport as soon as it was open.

This is all to say that when I reached Cebu, a beach day sounded really nice. But I was determined to find the reporters' temporary hideout. Fortunately, locating it -- a story, perhaps, for another time -- also meant finding a beach, albeit not one with glimmering white sands or an endless supply of cocktails at the ready (though one with stunning views that Annalee and Mel would have shared, and one with amazing, hospitable locals who invited me onto their porches). After sticking through to find the club, lechon seemed like a good reward, and I enlisted a group of boys in the nearby village to help me find the best stand around. Despite their dogged efforts, every place the boys took me was closed (as were other eateries). So I decided instead to save myself some hassle and grab a cab back to Cebu City and the airport on Mactan. On the way, I was happy to see that one of Cebu's most highly-touted lechon restaurants had a location near the airport. I was early for my flight, so I told my driver to stop there so I could get my long-anticipated award.

To be honest, the the smoothie I had there was better than the lechon, though I know understand the error of ordering a smoothie in a place where one is urged not to drink the water. While I'm not sure which dish led to the bacterial infection I'd discover in a few hours on my flight to Shanghai, my lechon stop came with another bonus. I'd already spent my remaining pesos on the cab and didn't want to withdraw more before leaving the Philippines, so I used a credit card to pay. I hadn't been worried about security as the place I was eating was a widely-known, well-appointed business on Cebu. But a week later, after I was back in the United States, the bank that issued that card called me to ask if I'd indeed spent $12,000 on sporting goods from Under Armor. Besides not knowing HOW one spends twelve grand on sporting goods, given how frequently I've hit my head on credit limits this year I couldn't help but be amused by the absurdity of the matter; fortunately my laughing credit card rep could see how absurd the situation was and immediately understood that I hadn't authorized the purchase.

This is all to say that when I woke up at 3:30 this morning with my stomach reeling, I realized that the last time I spent seven hours half-awake and crouched over a toilet was in the stall of a Shanghai hostel's co-ed bathroom, where I voided the last of that lechon. Thankfully, I maintained my composure just long enough to avoid doing so across a Chinese customs inspector's desk. Dodging the international incident that was sure to come just long enough, I instead ejected my meal in an airport bathroom, then gathered my faculties enough to repeatedly shout "búyào" (don't want) at the taxi-scammers who even at 1:30 a.m. swarmed around lǎowài (foreigners) like me, rode to the city, and began my uncomfortable introduction to Shanghai. I took the next three days to recover, but I finally did, and with just enough time to grab one more Chinese meal before I left for my long flight back to the United States.

I recount all this because I'm also reminded of another fact; as uncomfortable as my food-poisoning was and as harrowing as I may have found my journey across Panay, I experienced it fully aware that Mel and Annalee's own journey to Cebu had been on a boat that had to travel by night, that it they had taken it panicked by Japanese reconnaissance planes that circled over their heads on idyllic Philippines beaches, and that they'd fled again just before an enemy cruiser reached Cebu and shelled the city, only to sail into an ocean filled with threats hoping one day to tell their story.

I hope I've done justice to that story. You'll be able to decide whether I have done so on June 21.

P.S. If you'd like to help me acquire my own sporting goods, Pepto-Bismol or seatbelt, I'd truly appreciate your contribution.

Search Posts

Archived Posts

- March 2024 1

- October 2023 1

- October 2022 2

- December 2017 1

- April 2017 1

- February 2017 1

- January 2017 1

- November 2016 2

- August 2016 2

- July 2016 2

- December 2015 1

- November 2015 2

- September 2015 3

- April 2015 1

- March 2015 1

- February 2015 1

- January 2015 4

- August 2014 1

- May 2014 1

- April 2014 4

- March 2014 6

- December 2013 1

- November 2013 1

- August 2013 3

- May 2013 2

- April 2013 1

- December 2012 3

- November 2012 2

- October 2012 2

- September 2012 3

- August 2012 6

- July 2012 4

- June 2012 1

- May 2012 6

- April 2012 2

- March 2012 3

- January 2012 2

- September 2011 2

- August 2011 2

- July 2011 1

- May 2011 9

- April 2011 2

- March 2011 1

- January 2011 2

- November 2010 1

- October 2010 1

- August 2010 3

- July 2010 1

- June 2010 1

- May 2010 12

- April 2010 2

- March 2010 1

- January 2010 1

- December 2009 1

- November 2009 4

- October 2009 2

- September 2009 2

- August 2009 1

- July 2009 1

- June 2009 4

- May 2009 1

- March 2009 5

- February 2009 4

![Restaurant Rosenthal With Bike in Foreground [Good shot] Shanghai.jpg](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/51db1d79e4b03e2f06324d97/1473379937704-QU4YB2Z2NR49I06U7QDN/Restaurant+Rosenthal+With+Bike+in+Foreground+%5BGood+shot%5D+Shanghai.jpg)

![Man on Donkey on Chungking steps [very good image].jpg](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/51db1d79e4b03e2f06324d97/1469649822066-D9BWG7FESO76DNZZDA1H/Man+on+Donkey+on+Chungking+steps+%5Bvery+good+image%5D.jpg)